Former Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue

1897–9, rebuilt in 1947–60, closed and converted for use by the East London Mosque in 2015–16

The north side of Fieldgate Street around 1900

Contributed by Survey of London on July 2, 2018

From about 1896 there were synagogues on Fieldgate Street’s north side, behind Nos 33–35, adjoining and seemingly adapting part of Harris Grodzinski’s kosher bakery at No. 31, which had been established in 1888 and was to endure and gain renown. The synagogue, sometimes known as the Chevra Kehal Chasidim, meaning it served members from a variety of Chasidic sects, was rebuilt in 1900 as the Brodyer Synagogue, after members from Brody, Austria (now Ukraine). Despite this renewal, the _shul _was refused admission to the Federation of Synagogues; Lewis Solomon found it the most dangerous building he had ever surveyed. Even so, it clung on until at least 1928. There was also what must have been a tiny synagogue at 9 Fieldgate Street in 1901. These buildings were obliterated in the Blitz.1

Around 1900 many of the street’s two-storey houses were replaced with taller tenements, principally for Jewish occupants, and largely by various combinations of the Davis brothers, the Jewish family of developers who rebuilt so much of Whitechapel. ‘Davis’s Terrace’ (40–72 Settles Street) of 1890, just south of Fieldgate Street was an early speculation by Israel and Hyman Davis, who later traded as Davis Brothers. The old Black Horse and Windmill pub was displaced by redevelopment for a row of tenements of two- and three-room dwellings, put up by Maurice Davis in 1896–7 as 13–25 Fieldgate Street. Rather differently, 37–39 Fieldgate Street was rebuilt in 1911 as a four-storey neo-Georgian block of shops and dwellings, designed by William Stewart, architect. This too fell to bombing. The west end of the street’s north side survived the war, but was cleared around 1970 for road widening at the corner.2

Immediately west of Orange Row, on the site of the south part of Hodge’s sugar refinery, where the Maryam Centre now stands, two blocks of artizans’ dwellings were built in 1890 by the Great Eastern Railway Company. Known as Great Eastern Buildings, these comprised forty-eight flats in stolid and warehouse-like four-storey structures. They were demolished in 1972–3 and the GLC immediately thereafter allocated the site to use for a temporary building to house the relocated East London Mosque.3

Across Orange Row to the east, on the south part of the Brunning House site at 43–53 Fieldgate Street, a row developed by Edward G. Tagg in 1885–8 included the True Friends Beer House at its east end. Around 1915, not long after it found itself adjacent to Tower House, this became a temperance restaurant.

-

Jewish Chronicle, 20 Oct. 1899, p. 28; 16 March 1900, p. 27; 31 Jan. 1902, p. 25; 4 June 1926, p. 22: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), W/PRI/3/49: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), District Surveyor's Returns (DSR): Goad insurance maps, 1890–1953: Post Office Directories (POD): Geoffrey Alderman, The Federation of Synagogues, 1887–1987, 1987 pp. 12–13 ↩

-

DSR: Goad maps, 1890 and 1899: The National Archives (TNA), IR58/84790/735–66: POD: THLHLA, Building Control file 40647: Ordnance Survey maps: Isobel Watson, ‘Rebuilding London: Abraham Davis and his Brothers, 1881–1924’, The London Journal, vol. 29/1, 2004, pp. 62–84 ↩

-

LMA, Collage 118584–92: THLHLA, Building Control file 40631 ↩

-

Royal London Hospital Archives, RLHLH/S/1/4; RLHLH/D/3/6; RLHLH/D/3/24, p. 16: DSR: TNA, IR58/84790/775–9 ↩

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue

Contributed by Survey of London on July 2, 2018

The Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue was founded and built in 1897–9 on a ninety-year lease of land previously occupied by a house and workshop from where a ginger-beer maker and a dealer in tea chests had traded, immediately southwest of Hodge’s sugar refinery. This was a ‘model’ synagogue project whereby the Federation of Synagogues oversaw the amalgamation of three small chevros through appeals that condemned existing premises as unsuitable for public worship. With costs estimated at £3,500, the Federation contributed £500, members raised £700 and Samuel Montagu put down £200 of his own money. No doubt, Montagu supplied much of the shortfall. He was made Honorary President, while Charles N. Rothschild performed the opening ceremony. Solomon Michaels, a clothier, was the Acting-President.

The somewhat obscure City-based William Whiddington was the architect. Whiddington had a successful if unexciting practice in shops, offices, factories and warehouses in and around the City and West End. He specialised in dilapidations and light and air cases. It is not known how he landed his sole ecclesiastical commission for a synagogue, but it is notable that his offices were in the same streets (Finsbury Pavement and Queen Street, Cheapside) as those of Nathan Solomon Joseph, the United Synagogue architect. The Fieldgate Street congregation would probably not have been able to afford Joseph’s fees. Lewis Solomon, the Federation’s architect, does not seem to have been involved.

Responsibility for building work appears to have been passed around. James Sydney Voak of Tredegar Road notified the District Surveyor, but Sheinman & Noah of Cannon Street Road (probably Jewish to judge by the names, and possibly associated with Samuel Lissner, also on Cannon Street Road and active elsewhere on Fieldgate Street) were contracted in April 1898 and paid £860 for erecting and furnishing the synagogue. Finally, Charles Richard Gurr of Chiswick was paid £1,344. Cast-iron columns were supplied by H. Young & Co., of Eccleston Ironworks, Pimlico.

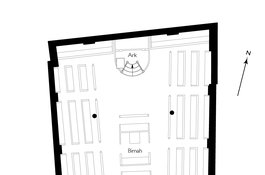

A ‘house’ in front of the synagogue, designed to be four storeys but reduced to three in execution, comprised a shop, a first-floor caretaker’s flat and a top-floor committee room. To the right of the shopfront double iron gates opened outwards for two entrances, one for women leading directly to a staircase accessing the gallery, and one for men giving onto a corridor to the main floor of the synagogue behind. The long room that formed the shulwas spacious, well-lit and ventilated, with accommodation for 280 men below and 240 women in the three-sided gallery. On two tiers of paired Corinthian columns, the ceiling rose to a part-glazed seven-sided central vault. The floor plan was in accordance with Ashkenazi tradition, the bimah (reading platform) being in the centre flanked by high-backed benches on the long walls. Extra rows were inserted behind the bimah. However, here, as in some other East End synagogues, the constraints of a long thin urban plot with access from the south made correct internal orientation of the Ark containing the Torah scrolls towards Jerusalem challenging and impractical. Against the back wall at the north end, the Ark had a tall upper tier with large Luhot (Decalogue tablets) flanked by Lions of Judah and topped by a semi-dome. Above there was a large round window.1

This synagogue, which had the official Hebrew name of Sha’ar Ya’akov (Gate of Jacob), came to be known as the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue to differentiate it from the several smaller synagogues along the street. It was badly damaged in the Blitz. A first phase of essential repair with new steelwork and concrete roofing for the main hall was carried out in 1947–8 through Lewis Solomon & Son, architects, with S. H. & D. E. White, civil engineers, and R. H. Rhodes Ltd, builder. Work on the hall and gallery, retaining the Corinthian columns, was completed in 1952 by Ashby and Horner Ltd, builders, under the oversight of another successor firm, Lewis Solomon, Son & Joseph, and the synagogue’s chairman, Nathan Zlotnicki. After an interval for fundraising and ‘lengthy and strenuous negotiations’, rebuilding of the ‘house’, now redenominated a ‘communal centre’, was carried through in 1959–60, Ashby & Horner giving it a reconfigured ground-floor layout and a plain front, brick above a rendered lower storey. New dedicatory inscriptions were put in place above and beside the main entrance. For many years the synagogue stood in isolation, continuing to thrive through amalgamations.2

Despite the rebuilding, the character of the synagogue’s interior was sustained. In large measure this was thanks to the leadership of the Rev. Leibish Gayer, stalwart here through the later twentieth century. Monument- lined, the passage along the east wall led back, as before, into the shul where the marbled columns and some old pews survived. The remade Arkbore humbler Luhot and carved and gilt-painted Lions of Judah. Left of the Ark was a stone Royal Family prayer tablet, a tradition imported from seventeenth- century Amsterdam that endured especially in more anglicised synagogues. Above the Ark two high-level round windows were given Star of David stained glass. There were also Star of David light fittings, and a large ceiling lantern lit the whole space. Panelled gallery fronts served as donation boards, bearing commemorative inscriptions.

The synagogue had a reduced capacity of just 150, and attendances continued to fall gradually away as the local Jewish population declined. By the turn of the twenty-first century a movable curtained trellis mechitzah was installed at the rear of the ground floor for a dwindling number of elderly women, so that they no longer had to climb the stairs. A substantial membership endured, but regular services had stopped by 2009. The Federation sold the building to the East London Mosque in 2015 by when it had come to be enclosed and dwarfed by the expansion of its young neighbour. In a conversion of 2016 designed by Makespace Architects, furnishings were removed and a new shopfront was created for a Zakat Centre (for the receipt of donations to charity). The Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue had been a remarkable survival, the last active synagogue in Whitechapel proper, and a reminder of the character of the numerous back-room synagogues that were once widespread in and around Whitechapel.3

-

Jewish Chronicle (JC), 23 June 1899, p. 2; 21 July 1899, pp. 18–19: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), Building Control file 40634: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), District Surveyor's Returns; ACC/2893/113 and 120: Post Office Directories: Charles Welch and W. T. Pike, London at the opening of the twentieth century, 1905, pp. 205, 298: Survey of the Jewish Built Heritage in the UK & Ireland: Sharman Kadish, The Synagogues of Britain and Ireland: an architectural and social history, 2011, pp. 153-4 ↩

-

THLHLA, BC file 40634: LMA, ACC/2893/118–22: East London Advertiser, 31 Dec. 1965 ↩

-

JC, 26 Jan 1990: Paul Lindsay, The Synagogues of London, 1993, pp. 51-3: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

The Great Synagogue seen in 1977

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 19, 2016

The Great Synagogue surrounded by cleared sites now occupied by the East London Mosque, London Muslim Centre and Maryam Centre, from a digitised colour slide in the collection of the Tower Hamlets Archives:

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue in 2003, prayer board dedicated to the British Royal family

Contributed by Peter Guillery

Former Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue, April 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Former Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue, April 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue as built in 1898–9, cutaway isometric view from the south-west

Contributed by Helen Jones

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue in 2003, view of the interior from the south gallery

Contributed by Peter Guillery

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue in 2003, view to the Ark on the north wall

Contributed by Peter Guillery

Fieldgate Street synagogue in 2003, view across the gallery looking east

Contributed by Peter Guillery

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue in 2003, dedicatory inscription in entrance passage

Contributed by Peter Guillery

Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue, ground-floor plan as designed in 1898

Contributed by Helen Jones

Nat Roos speaking in the synagogue, 2011

An interesting piece of amateur film shows Nat Roos addressing the congregation at the Great Synagogue about its history and memories of Jews in Whitechapel more generally

Contributed by Aileen Reid on Dec. 2, 2016

Choral Selichot service at the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue, 2011

Contributed by Aileen Reid on Dec. 2, 2016

East London Mosque film of interior of Great Synagogue

A short film made by the ELM showing many of the rooms within the Great Synagogue, at the time that the Mosque was acquiring the building in 2015

Contributed by Aileen Reid on Dec. 2, 2016

Interior of the synagogue in 2015

This is a video I took in the Fieldgate Street Synagogue in Whitechapel in 2015, after it had closed and been sold, but while most of the interior was still intact. When I was in the building the call to prayer started from the neighbouring East London Mosque, so the video is a evocative combination of the two traditions.

Contributed by Shahed Saleem on March 4, 2018