Anne Thorne talks about designing the Jagonari Centre

Contributed by Survey of London on Oct. 24, 2017

I was working at Matrix, a feminist design cooperative which I helped found with some other women, and we were approached by various women’s groups, one of which was Jagonari, who came to us [in 1982] and said they’d got a plot of land next to the Davenant Centre which was going to be turned into a community centre for local people, and that they wanted us to help them and advise them about what they could do on the site.

They said they wanted a place [for] childcare, they wanted a place to have big meetings, to play badminton - they wanted all sorts of things. We asked how much funding did they have and how big is this building. They said they thought it could be a Portakabin and they could fit everything in there. We asked, how many people do you think there are.

What became clear was that there were a lot of women who would use these facilities if they were available, and they did a lot of research [within] the local community. It was a really interesting group of women who started it, they were from mixed Asian communities, there was a Hindu women, a Bengali Muslim woman, a Bengali woman who was not Muslim, so quite a mixed community.

We’d been talking about being feminist architects quite a lot, and talking about how few women there were around who were architects at that point. When we set up Matrix there were approximately 5% of architects who were women, so we were in the minority. And once women heard about us they were very keen to use us.

Matrix was set up in 1982, and this was the biggest earliest project that we did, so it was quite exciting. The whole ethos of Matrix was if women haven’t ever been architects, how do we know what women would like, and on the whole women haven’t actually been asked what they want, they make do and women are generally very good at making do.

So when they said they wanted to do all of these activities we said, well that doesn't sound like a single story building in a Portakabin, that sounds like quite a big building, why don’t we see how big the building is and then go to the GLC who at the time were talking about funding this project and saying that they were very concerned that there was no provision within the Davenant centre for any women’s organisation.

It was an empty site, through bomb damage, with just a hoarding. It belonged to the Davenant centre, which was a derelict school, in a real state, quite extraordinary.

[Jagonari was founded by] five women who came together and said we’ve got to something about what’s going on locally and find a space for women to meet. There were a lot of issues in the local area about particularly a much older generation of men who had been in that area for some time, and there were a young group of women coming over to marry the men, and who were finding the change really difficult and finding life in London very difficult, and actually didn’t have the family support or connections that they had back home and were feeling incredibly isolated and really needed the facilities such as the creche and a place to eat and learn to cook and understand English as a foreign language teaching, learn how to use the library as their own resource.

So the women who were involved in setting it up were very much involved in those different communities in different ways, and were quite a strong group of women.

[The founders were] mostly Bangladeshi women, two of them were not. The whole idea was that it would be for Asian women but not centred on any one religious community, and they felt that was really important this it would welcome people from all communities but be specifically tailored.

We put these drawings together and had it costed and it was estimated at £690,000. So we put in an application to the GLC and much to our amazement we got the money, so the GLC funded the project.

They [Jagonari founders] were very convincing women.

On the design of the building

An important aspect of the building was that it was the first fully accessible building, with full disabled access.

The courtyard was geometric, and we spent quite a lot of time talking about symbols and geometry and what could and couldn’t be used. It was really important issue for the women.

Initially we had a very different design [on the front elevation] from this one, but the people from the Historic Buildings Council were very concerned that it should match the Davenant Centre, which we thought was a mistake because of the rhythm of that street. So in the end it ended up being a compromise between what English Heritage would accept and [a design that reflected the cultural identity of the users].

Initially Jagonari said they didn't want the building to have an Asian feel to it. There had been an awful lot of very serious attacks on the Asian community shortly before. All of the women in the group had had something put through their letterbox. So they were really concerned about security. But gradually as we talked through the building and as they got the money and things emerged that people got really excited about they felt really proud about the building, and the attitude changed, which was really nice.

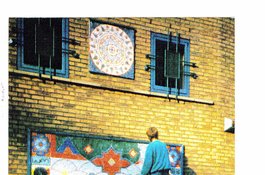

In the end we ended up with this metalwork over the windows with 11mm laminated glass behind it, because they [Jagonari] were really concerned that people would throw things, missiles, at it. The metal screening was partly about giving privacy and partly about security and the design came from studying lots of Asian buildings and talking to the group about what they wanted. We asked everybody to bring in photographs that expressed what they thought a building should look like. We had various options for the designs. [The mosaic pattern around the entrance door was] designed by [the artist] Meena Thakor.

On the first floor there is a hall which is accessed by the lift and stairs. This was a taller floor to ceiling height than the other floors, with a potential for a stage in the hall, for music and weddings, performances.

On the second floor, classrooms, a library, and a media resource room. On the upper floors admin offices and resource rooms.

The building was very well used and I was asked to come back and extend the creche at the rear. There were lessons going on, mother tongue teaching, it was used from morning to night. It was a really important hub. They were funded from the creche facilities and gradually got funding from different people.

Anne Thorne was in conversation with Shahed Saleem on 16.10.17

Sufia Alam's recollections of working at the Jagonari Women's Centre

Contributed by Survey of London on Oct. 6, 2017

I started at the Wapping Womens’ Centre in 2009…. And I was also a senior manager at the Jagonari Centre in the bigger projects, which was empowering and timely for me, it enabled me to come out of my comfort zone.

One of the projects that we did was the ‘End It’ programme for domestic violence, which was a big milestone for this community because especially women’s organisations got a lot of bad press around women breaking marriages, as perceived by men. So it was a nice project we did with the mosque, it was my first encounter of getting the mosque on board.

The Jagonari was going through some difficulties in 2013, and soon after I left it went into liquidation…. The Jagonari Centre was inclusive to women, not just Bangladeshi women, which is what it set out to be. Our focus was to empower women to be active citizens within the community, and this was happening. Women were progressing well in education, taking up careers, jobs, training. So we felt that we could offer that to more women.

One of the successful projects that came out was ‘Women Ahead’ which was working with women offenders who had come through the prison system, and we were integrating them back into society. So we had Muslim and non-Muslim women, and women from other faiths working together. Some people found it difficult because they didn’t like that change, and I think that’s where things went a bit pear-shaped. When you introduce a different community change will happen, and especially with that particular project it was women from a particular group where integrating them was a different process than integration Muslim or Bangladeshi families. These were women, Muslim, Hindu, Christian, who had been through the Criminal Justice System or they’d suffered domestic violence through which they were driven to criminal acts. We were working with them in assisting with employment and empowerment that would prevent them to offend again.

There were some Bangladeshi women, Pakistani and mostly English women. Even though the majority of the young senior managers felt this was the place where a wide range of communities could be served, the managers felt this should not be the focus of Jagonari. That, with the fact that the council put in a corporate rent, which went from peppercorn to corporate, which meant that with the market values around here, we couldn’t afford to pay, and along with funding cuts, it made it very difficult to stay.

We fought a legal battle in terms of trying to get the original lease retained, so a lot of the surplus was used up in legal costs, and that’s where it went downhill, and a lot of people were laid off.

Sufia Alam was in conversation with Shahed Saleem on 15.05.17

.jpg.265x175_q85_crop-0%2C0.jpg)