Altab Ali Park, including the site of the parish church of St Mary Matfelon

Former churchyard with medieval origins, renamed in 1994

1978: The turning point of Bengali politics in London’s East End

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah on Jan. 9, 2018

The Bengali presence in the UK can be traced back long before the Indian subcontinent gained its independence in 1947. From the mid-19th century onwards a small number of Asian professionals, mainly doctors, businessmen and lawyers had established themselves in Britain. In the beginning of the 20th century the first large group of South Asians who came to the UK were seamen, known as lascars, including Bengali seamen recruited in British India to work for the East India Company. Groups of seamen and ex-soldiers settled nearer the docks of East End of London.

1940s-1950s: Welfare of fellow countrymen

Some of these seamen began to settle in London’s East End from the 1850s onwards. Evidence of the early settlement of Bengali seamen in London can be seen in the formation of organisations such as the Society for the Protection of Asian Sailors in 1857. But an early and influential Bengali figure connected to the East End of London was Ayub Ali Master, who lived at 13 Sandy's Row (1945-59). He ran a seamen’s café in Commercial Road in the 1920s and also then opened the Shah Jalal Coffee House at 76 Commercial Street. The Commercial Street premise is still there used as a trendy bar/restaurant known as Blessings in 2017. Ayub Ali Master turned his Sandy’s Row home into an advice centre of support for Bengalis which included a lodging house, a job centre offering letter writing, form filling and a travel agency. He also started the Indian Seamen’s Welfare League in 1943. As a result most seamen headed for Ayub Ali Master’s coffee shop which was usually the first port of call for help and guidance. By the 1950s the Bengali population gradually grew and mostly men, both seamen and others who arrived in the UK by ship and by air, had established the Pakistan Welfare Association which became the Bangladesh Welfare Association after Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971. The Bangladesh Welfare Association is the oldest and largest community organisation with a membership of over 40,000. The Bangladesh Welfare Association building since 1965 is situated at 39 Fournier Street, next to historical Brick Lane Mosque, originally built for the minister of the church in 1750. It was the base of Huguenot charitable work with the local poor. Jewish charities were based here at the end of the 19th century. Until recently the Bangladesh Welfare Association building also happened to be the contact address for the Altab Ali Foundation.

1960s-1970s: Bangladeshi politics - Liberation War

From the early 1950s and throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, political developments in Pakistan and especially in East Pakistan, where Bengalis came from, were moving fast. Pakistanis were campaigning against military rule. In addition the Bengalis of East Pakistan felt that they were getting a raw deal within the framework of Pakistan. As result resentment grew against the Pakistani ruling elite based in West Pakistan. The cause of the people of East Pakistan was being championed by a party called the Awami League led by a young charismatic leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Awami League’s demand for self-autonomy soon turned into the full-fledged Independence War of Bangladesh in 1971. During the War of Bangladesh in 1971, the UK’s Bengali community played an important role in highlighting the atrocities taking place in Bangladesh, lobbying the British government and the international community and raising funds for refugees and Bengali freedom fighters. The Bengali community across the UK formed Action Committee’s in support of the liberation of Bangladesh. A key feature of this period was the support provided by members of the white British majority. Among some of them was our very own Peter Shore MP from East London. It is interesting to note that Bengalis were active in political activity before 1971 as they had supported Awami League’s Six Point programme in 1966, which demanded greater autonomy for East Pakistan and campaigned for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s release following his arrest in 1968 in the Agartala conspiracy case. An important meeting venue for the Bengali activists during 1971 was the Dilchad restaurant near Artillery Lane in East London. The owner of the restaurant, Mr Mottalib Chowdhury, was a prominent social worker. There were hardly any Bengali students who did not receive help from him. His sons followed their father’s footsteps and still are active in community and social work.

1978: The Turning Point - Political mobilisation of the second generation

Bengali community activists and anti-racist politics

From the mid-1970s many British Asians, including Bengalis who lived in the East End of London, were experiencing racism, social deprivation and a high level of unemployment. For the Brick Lane Bengali community, who had been under constant attack from racists since early 1970s, the murder of Altab Ali, a leather factory worker, in 1978 was a turning point, especially for the Bengali youth. The murder led to their mobilisation and politicisation on an unprecedented scale. On 14 May 1978, 10,000 locals marched from the then St Mary’s Gardens (now Altab Ali Park) to a rally in Hyde Park, walking behind the coffin of Altab Ali in a show of unity and strength against racial violence. The group then walked to 10 Downing Street to hand over a petition to the Prime Minister calling for action to be taken against racist attacks. This was one of the biggest demonstrations by the Bengali community since the rallies for the independence of Bangladesh in 1971. In the same period the Bengali community began to organise youth groups, community and campaigning groups and linked up with other anti-racist movements and organisations. The groups that came out of this struggle were the Bangladesh Youth Movement (BYM), Bangladesh Youth Front (BYF), Progressive Youth Organisation (PYO), Bangladesh Youth League (BYL) and the Bangladesh Youth Association (BYA) amongst others. In fact 1978 saw the emergence of the second generation of Bengali community activists who would later enter mainstream politics in the 1980s.

Naming of Altab Ali Park and Altab Ali Arch

Altab Ali Park has now become symbolic to the Bengali community. To mark the death anniversary, the Altab Ali Foundation was set up in 2010 to hold annual vigil on 4 May 2010 known as the Altab Ali Day. Usually hundreds of community leaders, activists and anti-racist activists attend in solidarity against racism and extremism in the East End. After a long standing demand from the local community, St Mary’s Gardens was renamed Altab Ali Park in 1998, an initiative brought forward by the Stepney Neighbourhood of Tower Hamlets Council to commemorate the racist murder of Altab Ali. Before that it was called St Mary’s, the site of a 14th Century white church called St Mary’s Matfelon from which the local area – Whitechapel- derived its name. It was bombed in the Blitz during World War II, and a lightning strike a few years later finished it off, only a few graves stones remain today. As you enter Altab Ali Park, from White Church Lane/Whitechapel High Street you will pass under the Altab Ali Arch. This Arch commemorates Altab Ali and other victims of racist violence. In 1989, David Peterson, a Welsh artist and blacksmith was commissioned by Tower Hamlets to make a wrought iron arch for the entrance of the park. The design is based on both Bengali and European architecture. It comprises of red coated metal wrapped around and interwoven through a tubular structure. This is meant to signify the merging of different cultures in the East End. Altab Ali Arch was erected on 25 – 27 September 1989 and unveiled on 1 October. A ceremony accompanied the unveiling in which there were speakers, Bengali music and stalls. A banner was commissioned from Cate Clarke which was hung from two trees facing Whitechapel Road. Hundreds of children from local primary schools, Osmani and Harry Gosling, made hats, flags, and ribbon accessories, and led procession through the arch after it was unveiled.

1980s: Community representations from the 1970s-1980s

In the 1970s and 80s, Bengali community politics moved away from preoccupations with political struggles in Bangladesh. Alliances were forged between some of the first generation and the younger activists. The energy of youth was consolidated in 1980 by the formation of the Federation Bangladeshi Youth Organisations (FBYO), an umbrella body that spearheaded campaigns for better housing, health and education and against racism. The FBYO was the first truly national campaigning organisation that made representation of Bengali interests and spoke for Bengalis across the borough and nationally. The youth seized the opportunity to gain both access to the local political system and to various funding streams channelled through the local council, the Greater London Authority and the education authority. They also saw the importance of building alliances with activists outside the Bengali community, such as other ‘Asians’ from Hackney, Newham, Camden, Southall, Bradford and those from the white majority community of East End. In the 1980s, 34 of the 112 community groups listed by local education authority in Spitalfields ward of Tower Hamlets were led by Bengalis. As Bengali community activism grew, many activists took prominent roles in community politics. Brick Lane became the centre of Bengali activism. Today Brick Lane has become a global icon, a branding concept as in ‘Banglatown’ and the ‘Curry Capital of Europe’. 1982 saw the first Bengalis elected to local council. Nurul Haque, an independent candidate from Spitalfields became a councillor defeating a Labour candidate. In the same year Labour’s only Bengali candidate Ashik Ali became a councillor from St Katherine’s ward. Today Tower Hamlets Council can boast the largest number of Black/Asian/Bengali councillors in any one borough. Today’s Mayor, Member of Greater London Authority, Member of Parliament and Member of the House of Lords are all directly linked to the legacy of the community’s effort, following the murder of Altab Ali, to challenge institutional racism and to enter mainstream politics in order to bring about meaningful changes for the greater welfare of the Bengali community.

Altab Ali Park

Contributed by Survey of London

On 4 May 1978 Altab Ali, a 25-year old clothing machinist of Bangladeshi origin, was murdered in Adler Street, Whitechapel, beside the park that was then called St Mary’s Gardens, a name that recalled the Church of St Mary Matfelon (the medieval ‘white chapel’) which had stood on the site until 1952.

This attack galvanized resistance to racism in the area and beyond. A decade on, Tower Hamlets Council commissioned David Petersen, an artist–blacksmith, to make the park’s wrought-iron gateway arch to commemorate victims of racist violence. Put up in 1989 at the park’s Whitechurch Lane corner, it playfully combines Mughal and Gothic ornamental motifs. Following a local campaign, the Council renamed the gardens Altab Ali Park in 1994. Five years later the south-west corner of the park gained a Shaheed Minar (Martyrs’ Monument), a semi-circular concrete plinth with five white steel screens, representing a mother and children, the former to the centre bow-headed in front of a blood- red circle. This is a smaller version of a Shaheed Minar in Dhaka, Bangladesh, designed by Hamidur Rahman, which commemorates activists of the Bengali language movement killed in 1952. Long desired and petitioned for, a Whitechapel monument began to be planned in earnest in 1996, though not at first with this site in mind. The Bangladesh Welfare Association marshalled contributions from 54 organisations and worked closely with the Council. Another copy of the Dhaka monument was made in Oldham in 1996–7. Its designers, the Free Form Arts Trust, were brought in and commissioned to make Whitechapel’s structure larger. Landscaping and the plinth were handled by the Council, and Arts Fabrications made the monument. It was unveiled on 17 February 1999 by Humayun Rashid Choudhury, Speaker of the Bangladeshi Parliament.

Altab Ali Park in 2014

(photograph by Lucy Millsom-Watkins)

Altab Ali Park in 2014

(photograph by Lucy Millsom-Watkins)

Since 2000

Further landscaping followed in 2002 with a new diagonal path through the churchyard that bore an inscription of part of a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, ‘The shade of my tree is offered to those who come and go fleetingly’. The lettering disappeared when another relandscaping of Altab Ali Park was undertaken in 2011. The layout that followed was designed by muf architecture/art as ‘a matrix of the religious and the secular’,1 and celebrated as ‘a grand collage’.2 It includes a raised green terrazzo walkway and bench that marks parts of the outline of the site’s Victorian church. Stone fragments carved by apprentices at the Building Crafts College were scattered to suggest the lines of the preceding church. Further south, hillocks, boulders and tree stumps articulate the land east of the Shaheed Minar and, with a small platform, open up a longer view of the monument.

On 4 May 2016, Tower Hamlets Council launched Altab Ali Commemoration Day as an annual event.

Earlier history as a churchyard

Whitechapel’s first churchyard is said to have been extended westwards up to Church Lane at an early date and then to have been enlarged southwards in 1591 when the south aisle was built. Further southerly extension, even crossing the parish boundary to the south-east, to make the churchyard almost co-extensive with the present-day park was achieved in 1627 and 1665. By the 1650s, perhaps much earlier, the churchyard was walled round, but the southern extension was possibly not walled before the 1750s. Land immediately east of the church was given over by the 1650s to a large property set back from the road that was probably the rectory. It was certainly such when it was replaced in brick some time before 1682, most likely by the Rev. Ralph Davenant. This house was built up to the street in front of a private walled garden.3 The rectory was again rebuilt in the early 1760s for the Rev. Roger Mather, on a smaller footprint set back from the road, double-fronted with full-height canted bays.4 It took its final form in 1838 in another rebuilding, this time for the Rev. William Weldon Champneys and to plans by John Samuel Erlam of Pink and Erlam, architects. They produced a deeper double-pile building, again double-fronted with a thinly classical façade with outer pediments. Two of Champneys’ five sons born here went on to eminence, Basil Champneys (1842–1935) as an architect, and (Sir) Francis Henry Champneys (1848–1930), as an obstetrician. The vicarage was destroyed in 1940.5

Notable burials in the churchyard included those of Richard Brandon, 1649, said to have been the executioner of Charles I, Sir John Cass, 1718, and Richard Parker, the Nore mutineer, 1797.6 Levelling and landscaping of the churchyard in 1800–5 included a footway from the church’s west door to new gates at the Church Lane corner, south of which a small watch house was built. Iron railings on dwarf walls replaced earlier churchyard walls in the early 1820s and, to the east, in 1839. In the same years a fire-engine house was added to the south of the watch house and then enlarged to replace it. The vestry ceded control of the engine house and its two engines to the newly formed Metropolitan Fire Brigade in 1866. The Commercial Road Fire Station that opened in 1875 made the facility redundant.7

Despite the existence of another parochial burial ground to the east on the north side of Whitechapel Road since 1615, the churchyard was badly overcrowded in 1839. The surgeon George Alfred Walker found it ‘extremely disgusting … so densely crowded as to present one entire mass of human bones and putrefaction.’8 In 1846 appearances were said to be ‘very far from creditable to the parish’.9 Burials ceased in 1854. A record from 1875 lists eighty-seven gravestones and monumental slabs in the churchyard.10 These have since been largely removed or tidied to the site’s edges, with the notable exception of a chest tomb for the Maddock family of timber merchants, a stout early nineteenth-century monument of Portland stone with a marble armorial panel, a pyramidal top and an urn finial. This remains in situ at what was the south-east part of the churchyard – land to its east was the rectory garden. Some other surviving gravestones were recorded in 2011. [B, 15 Aug 1846, p.388] With closure pending, the churchyard was planted with trees and shrubs in 1850–1 under the supervision of Samuel Curtis who had landscaped Victoria Park.11

The rebuilding of the church in the 1870s presented an opportunity to widen the adjacent stretch of Whitechapel Road, so in 1878 the still existing stone- coped red-brick boundary wall went up along a new setback line. It was designed by Ernest C. Lee and built by S. (Sydney) & E. Jacobs of Leman Street, using Allen’s Suffolk bricks identical to those used to face the church. It was originally topped by short piers, ornamental iron railings and two gabled aedicules, one of which housed a war memorial from 1917.12 Two former entrances from the Whitechapel Road are now blocked, the larger one still marked by remnants of stone steps.

A drinking fountain had been put up in 1860 on the Whitechapel Road railing near the old church’s east end, ‘from one unknown yet well known’, as it is inscribed, perhaps a reference to Champneys given the date. With a gabled ragstone surround to a Norman arch with pink granite colonettes and back panel, the form of the inner parts closely imitated at a larger scale London’s first free drinking fountain, put up at Snow Hill in 1859. When the church was rebuilt the Whitechapel fountain was to have been rehoused in an apsidal recess, centred between seats in an equivalent position, but it was instead moved round to Church Lane in 1879, then, making way for the Clergy House in 1894, moved again a bit further north where it has stayed in front of a surviving section of the railings of the 1870s.13 A K2 telephone kiosk was placed to the fountain’s right around 1927 and a K6 kiosk followed in the 1930s. The former remains _in situ _and listed.14

St Mary’s Gardens

When the churchyard wall was built in 1878 it was proposed that tombstones and human remains should be moved to free part of the grounds for an ‘ornamental garden’.15 The transformation of the churchyard into a recreation ground was set to be carried out by William Holmes, of Frampton Park Nurseries in Hackney, but the work was delayed by the fire in the church in 1880. The objective was achieved in 1885 when the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association, with whom Holmes worked elsewhere, assisted in opening the churchyard as public gardens with an improved layout, seats, a caretaker, and an admission charge of a penny. Basil Holmes, the Association’s Secretary, and seemingly unrelated, made a survey of the graveyard in 1897. Public use was not sustained and in 1938 new proposals were made for improving the churchyard to be a public garden with ‘a few seats and shrubs to humanise this derelict spot’. These were blocked by the Rev. Mayo who was concerned that any such garden would ‘become the resort of undesirable characters’.16

War intervened. Once the ruined church had been cleared, and with the unfenced land indeed attracting uses that aroused criticism, the London County Council set out in 1957 to buy the churchyard to be a public open space, preparing a scheme for planting and landscaping. Legal delays as to title meant that it was 1964 before progress could be made. Parks Department works were carried out by Kinman Ltd, contractors, and St Mary’s Gardens opened in 1966. The upper parts of the boundary wall had been taken down, the Whitechapel Road entrances bricked up and railings put up along Adler Street. Around 75 to 100 gravestones, most already undecipherable, were set round the boundaries where others were already placed, and the footprint of the seventeenth-century church was set out in concrete blocks flush with the ground. First intentions had been to mark the medieval ‘white chapel’, but without funding for archaeology this was impossible. Complaints about vagrancy in 1968 led to the removal of shrubberies (‘a favourite haunt’), additional tarmac paving and replacement seating. The gardens were extended south to Mountford Street in 1969.17

-

Building Design, 11 March 2011, p.4 ↩

-

London Evening Standard, 16 Nov. 2011 ↩

-

Richard Newcourt, Repertorium Ecclesiasticum Parochiale Londinensis, vol. 1, 1708, pp. 698–9: William Faithorne and Richard Newcourt, map of London 1658: William Morgan, London etc Actually Surveyed, 1682: John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, vol. 2/4, 1720, p.46: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), P93/MRY/090; P93/MRY/091, pp.20,365–74; A/DAV/01/013/2 and 51; Q/HAL/308; GLC/AR/HB/02/375 ↩

-

LMA, Collage 22156: Richard Horwood, map of London 1792–9 ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/MS19224/441: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) sub Champneys ↩

-

_ODNB_ ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/090: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), L/SMW/A/1/1: Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes, 6 Oct 1865, p.1110; 9 March 1866, p.302: Horwood ↩

-

G. A. Walker, The Grave Yards of London, 1841, p.12 ↩

-

Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. 189, Dec. 1850, p.645 ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/092 ↩

-

Historic England, Greater London Historic Environment Record, MLO3933: Post Office Directories ↩

-

The Builder, 3 Aug. 1878, p. 812: British Pathé, Whitechapel’s War Heroes, 1917 ↩

-

THLHLA, LCF00550; P10077, P10099; L/THL/D/1/1/117 ↩

-

LMA, SC/PHL/02/1193 ↩

-

The Builder, 3 Aug. 1878, p.812 ↩

-

Hackney and Kingsland Gazette, 26 Sept. 1881, p.4: East London Observer, 22 Oct. and 10 Dec. 1938; 3 June 1939: LMA, CLC/011/MS11097/1–3; CLC/011/MS22290, No.133: Isabella (Mrs Basil) Holmes, The London Burial Grounds, 1896, p.296 ↩

-

LMA, GLC/AR/HB/02/375; SC/PHL/02/1193: THLHLA, L/THL/D/1/1/117; L/THL/G/1/10/7: East London Advertiser, 1 Oct. 1965 ↩

The Church of St Mary Matfelon

Contributed by Survey of London on June 27, 2016

Medieval churches

The first church on the site that is now Altab Ali Park was built in the mid thirteenth century (by 1282), dedicated to Mary and from the outset identified as ‘de Matefelun’. This, which became Matfelon, may derive from a family name; Richard Matefelun, a wine merchant, is said to have been present in the area in 1230. If this is the derivation (matfelon as meaning knapweed is the least preposterous of numerous suggested alternatives), it was presumably in recognition of a pious benefaction, whether prompted by local need or not. It does seem clear that there would have been significant population growth in the area, and that the existing parish church of St Dunstan, Stepney, aside from being distant had been outgrown. Parish status was granted by 1320, the vicarage being in the gift of the Rector of Stepney. 1

Archaeological evidence indicates that the church, always aligned to the adjacent road and not properly oriented, was of clunch or white chalk rubble. It thus, no doubt, came to be known as the ‘white chapel’, an appellation in use by 1344. Clunch was not uncommon in medieval churches, especially to the east and north of London, though it is friable so was often mixed with other materials. The building was reportedly wrecked in a storm and restored in 1362 thanks, it is said, to a papal Bull negotiated by the absentee rector, Sir David Gower, a Canon of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, that promised sinners a remission of penance for visiting Whitechapel with an offering. There were four priests in 1416 indicating a large congregation or at least a prospering parish. Documentation of legacies and archaeological investigation both point to fifteenth-century improvements, to the fabric of doors and windows if not more. 2 Exceptionally, there were no chantries at the Reformation, when, in 1548 there were 670 communicants. 3

Little is known about the form of the medieval church. It appears to have had a four-bay nave to which a three-stage crenellated tower and a north aisle and porch might have been fifteenth-century additions. George Birch’s claim from inspection of wall footings in 1876 that the medieval church was co-extensive with that of the seventeenth century seems doubtful, if only because it is known that a south ‘aisle’ was added in 1591. This was, it seems, separately roofed, and almost as tall as the nave, though not as wide, and possibly not as long. More a room than an aisle it would have generated not just more seating for a growing congregation, but also a much more auditory and less processional interior. That would have been in keeping with the Calvinist norms of the late sixteenth century that were strongly represented in east London and firmly upheld by Richard Gardiner (or Gardner), Whitechapel’s rector from 1570 to 1617. 4

Protestantism had sparked early in Whitechapel, through the celebrated challenge Richard Hunne, a merchant tailor and probably a Lollard, had presented to the claimed rights of the rector, Thomas Dryfield, in 1511, and through John Harrydance, the Whitechapel bricklayer, arrested in 1539 for preaching from his window. 5 Gardiner, in whose time the vestry sold off the church organ, was prominent among Elizabethan puritans and was embroiled in high-level religious–political controversy in the immediate run up to the extension of his church in 1591. 6

Seventeenth-century ructions and rebuilding

In 1618 William Crashawe, an outspoken and leading London puritan, became Whitechapel’s rector, a posting that brought him upwards of £32 a year. He oversaw the insertion of a gallery in the south aisle which suggests that capacity was already again stretched. It bore a panel to commemorate the failure in 1623 of the Spanish Match. Crashawe died in 1626, preceded by 1,100 of his parishioners in the plague year of 1625. His successor in what his will called the ‘too greate Parishe’ of Whitechapel was John Johnson, another puritan, but one who married the daughter (Judith Meggs) of a wealthy parishioner in 1627 and trimmed thereafter to align with the Laudian tide. 7 Johnson moved the communion table to the east end of the church, and undertook repairs in 1633–4 with £300 raised from parishioners and more from the Haberdashers’ Company, which in making the grant took into account the relative poverty of the parish. These works left the church ‘within and without, and in every part of it, Richly and very worthily beautify’d’. 8

Archbishop William Laud and such beautifying initiatives faced strong local opposition. Johnson was among the first London clergy to be deprived of his living in 1641. In the early 1640s Thomas Lambe’s General Baptists formed in Whitechapel what was at the time ‘easily the most visible and notorious of all sectarian congregations in London’. 9 After contested elections for parish overseers and violent confrontations in the church in 1646, Whitechapel’s Independents gained control and gathered under a new rector, Thomas Walley (or Whalley). When the tables turned in 1660 Johnson was reinstated and a schism resulted, most of the congregation departing to a meeting house in Brick Lane. In 1662 Walley was arrested preaching elsewhere in Whitechapel; he soon after emigrated to New England. 10 Johnson was revealed as corrupt and deprived of his living in 1668, chiefly through the agency of his son-in-law, Ralph Davenant, who became the next rector of Whitechapel. A fellow of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and a descendant of Bishop John Davenant, the moderate Calvinist who had represented the English church at the synod of Dort in 1618, he was also a cousin to Thomas Fuller. 11

The largely medieval church was rebuilt in 1672–3. Davenant and the vestry came to an agreement about the project in January 1672 and work was probably complete by the end of 1673 which date was carried on a stone tablet that remained on the east side of the tower through subsequent rebuilds. Some joinery and other work was yet to be finished in June 1675. The principal benefactor was William Megges, who had one of the parish’s largest houses where Johnson, his brother-in-law, had lodged in the 1650s. Megges had been a member of Johnson’s vestry from 1660 and commemorated his parents' earlier patronage of the church with a large black-and-white marble aedicular mural monument. These links with Johnson notwithstanding, Crashawe’s panel of 1623 was relocated onto the new south gallery and a monument to Crashawe himelf was conspicuously re-erected on the north wall. Puritan inheritance was not obscured. 12

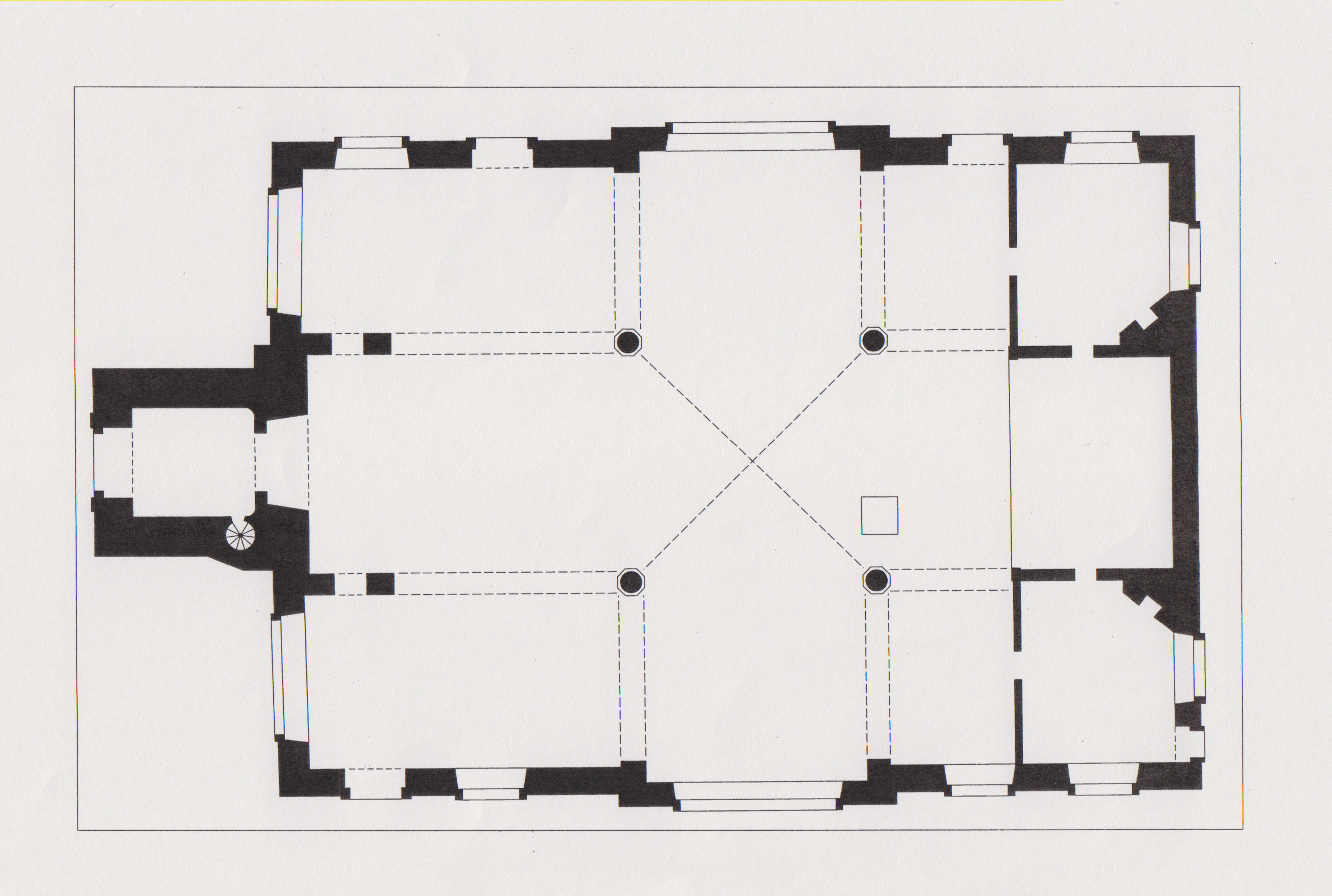

In its architectural form the new brick-built church represented a rapprochement with moderate Nonconformity. It reused some old footings and lower parts of the tower, but in its regular cross-in-rectangle plan, 90ft by 63ft, with shallow transept projections and angle quoins, it closely followed pre-Restoration Calvinist models at Westminster Broadway and Poplar. High- level round windows to north, south and east, perhaps derived from Inigo Jones’s work of the 1630s at St Paul’s Cathedral. The Serliana to the west also had pre-Restoration precedents in London. There were transept pediments to north and south, segmental pediments above inner-bay entrances to the north and pine-cone finials. The less prominent south side was more humbly finished, with an outer-bay entrance. The west door had rusticated pilasters, cherub- head capitals and a pediment. Architects and builders remain unknown, but there are circumstantial reasons for suspecting involvement on the part of Robert Hooke. 13 The assuredly if impurely classical auditory interior was ‘very lightsome and spacious’. 14 The main east-west axis was emphasized by three ribbed cross vaults supported by four Portland stone Corinthian columns, their bases obscured by box pews. There was a step up to the chancel, otherwise only articulated by the inclusion of flanking vestries. The chancel was backed by a pedimented and enriched Corinthian reredos. Shallow north and south galleries were probably original. A mural monument to Megges was erected after his death in 1678, identical to that he had put up for his parents in the 1660s save for its arms and inscription. 15

Church of St

Mary Matfelon, plan as rebuilt in the 1670s

Church of St

Mary Matfelon, plan as rebuilt in the 1670s

Vicissitudes, alterations and repairs, 1700 to 1860

Davenant was succeeded in 1681 by Dr William Payne, a latitudinarian, fellow of the Royal Society and leading Whig among London clergy who was keen to embrace dissenters. The living was reduced by the loss of Wapping from the parish in 1694, and the liturgical politics of Whitechapel changed dramatically in 1697 with the appointment of the Rev. Richard Welton, a high- church Tory and Jacobite. Welton attacked Nonconformity and spurned the area’s recent Huguenot immigrants: ‘This set of rabble are the very offal of the earth, who cannot be content to be safe here from that justice and beggary from which they fled, and to be fattened on what belongs to the poor of our own land to grow rich at our expense, but must needs rob us of our religion too.’ 16 He made beautifying alterations, moving the font and altering pews, oversaw the casting of six new bells by Phelps’s local foundry in 1709, and attracted high-profile controversy in 1713 when he placed a painting of the Last Supper by John Fellowes in the church as an altarpiece. Judas was prominently represented as a likeness of Bishop White Kennett, an antagonist of Welton’s. Through the Bishop of London, Kennett saw to the altarpiece’s removal in 1714. The same phase of works included an organ by Christopher Schreider, perhaps also the west gallery in which it stood. The organ case was later described as ‘carved and gilt, with carved oak trusses and gilt cherubim, surmounted by four richly-carved and gilt figures’ 17 The gallery front sported a finely carved wood panel depicting King David playing the harp flanked by musical instruments. This survives close by in the church of St Botolph Aldgate. Refusing to swear loyalty to the Hanoverian succession, Welton was deprived of his position in 1715. Figures of Moses and Aaron were thereafter placed flanking where Fellowes’s altarpiece had been. A square window above, seemingly with painted glass, was surmounted by a painted glory, rays of light representing the Holy Spirit. 18

The advowson was purchased by Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1708, then in 1711 the Commissioners for Building Fifty New Churches decided that Whitechapel needed two more churches.19 These did not materialize, but under a succession of latitudinarian rectors Whitechapel’s church appears to have steered clear of further controversy making it a quieter but duller place. It was ‘repaired and Beautified’ in 1735 and again repaired, in what was a wealthy parish, with funds raised through an Act of Parliament in 1762–3 when the tower, possibly unstable, was to have been cased in Portland stone – it was probably rendered instead. The clock stage gained aedicules and a large cupola took the place of the small bell turret. Similarities with the exactly contemporary St George’s German Lutheran Church on Alie Street suggest that the carpenter–architect Joel Johnson may have been in charge of this project. 20

The pulpit was to have been removed in 1771, but perhaps nothing was done – a carved oak pulpit on fluted columns and with a tented tester that does not look later in date was present a century later. 21 There were repairs worth £2,000 in 1805, with seats in the galleries divided into pews. Then in 1806 the pulpit was moved and there were more repairs for £4,133 11 2½, with James Carr as surveyor. These works probably included a cornice on the tower. By 1815 the east window had been replaced with an 18ft-tall arch-headed stained- glass Adoration of the Shepherds, said to have cost £600 and possibly by James Pearson. Structural repairs involving iron tie rods and costing £1,113 13 3½ followed in 1825–6, with John Shaw (the elder) as surveyor. Even so, the tower became dangerous. James Savage acted as surveyor for yet further repairs in 1829–30, for £1,686 8 4. To keep to the chronology and note in passing, on 12 January 1832 St Mary's was the location for the marriage of Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, age 19, and Sarah Ann Garnett, age 22, who died on 27 May 1832 a week after giving birth to their daughter Anne. In 1839 Edward Blore reported on the state of the church and recommended rebuilding. Discussion was adjourned for a year, but not resumed, the notion presumably deemed too costly. 22 The tower was again repaired in 1865, and given a new cast-iron bell frame made by Mears & Co. 23

From 1837 to 1860 the Rev. William Weldon Champneys was Whitechapel’s rector. An evangelical, he started with a congregation of about 100, in a population of about 34,000, and by 1851 had built attendances up to more than 4,000 across three services on a Sunday. He brought numerous reforms to Whitechapel, from a Sunday school and mothers’ meeting, to ragged schools and a coal club and shoe black brigade. He attempted to convert Whitechapel’s many Jews, and battled cholera and house farmers. Champneys also divided the parish, founding three new churches. 24

Victorian rebuildings

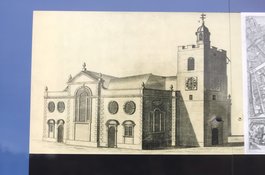

An inspection in advance of an intended redecoration led to another condemnation of the seventeenth-century church as structurally unsafe in 1873. The parish reluctantly geared up to spend £4,000 on essential repairs. Then, in June 1874, Octavius Edward Coope (1814–1886) came to the rescue. Coope's father and grandfather had been sugar refiners on the west side of Osborn Street where he continued before attaining greater wealth as a brewer. He was a founder of Ind Coope & Co. in Romford in 1845, which firm maintained an Osborn Street depot and expanded to Burton-on-Trent in 1856. Coope had been an MP in 1847–8, but was unseated on grounds of bribery. After a long interval he was again elected to Parliament as a Conservative MP for Middlesex in February 1874. With that newly acquired status, Coope stepped forward claiming to be a Whitechapel parishioner, though he had been born and lived in Essex and, when in London, resided on Upper Brook Street in Mayfair. He offered to pay up to £12,500 towards a new church, presenting plans by his architect nephew, Ernest Claude Lee, who had been a pupil of William Burges’s, for a red-brick and stone-dressed High Gothic Revival building to seat 1,400. The offer was initially accepted with great relief and joy, but Coope had soon to defend the proposed use of red brick, averring, wrongly, that ‘our great church architect Street invariably uses it’. 25 It was in fact to James Brooks’s recent red- brick churches in Haggerston, St Columba and St Chad, that a Vestry committee went for comparative inspection. This committee was led by the Rev. James Cohen, a converted Jew who had been Whitechapel’s rector since 1860, and subsequently spearheaded by Augustus William Gadesden, another sugar refiner. They were not impressed, convinced in their dislike of red brick, and anyway keen to have a larger church. Overall costs were estimated to be about £6,000 more than Coope was offering. Cohen’s committee concluded in September, with diminished alacrity, that ‘it is expedient that the offer of Mr Coope be accepted.’ 26 Rebuilding began in 1875 when Cohen was succeeded by the Rev. John Fenwick Kitto. The builder was John T. Chappell, of Little George Street, Westminster. Work was completed in October 1876 and there was a consecration in February 1877. The upper stage of the tower and spire followed in 1878, built by Edward Conder of Kingsland Basin. The estimated total final cost had risen to about £30,000 of which it was later said around £10,000 came from public subscription, the rest from Coope. 27

The large brick church comprised a nave (109ft long and 78ft high) and aisles, a round-apsed chancel, a baptistery under a west gallery and a three-stage north-west tower with an octagonal spire and corner turrets rising 175ft in all, sited so as to be prominent on the main road. It extended further west and south than its predecessor and was set less squarely to the road, to minimise disturbance of the graveyard and avoid building on southerly ground that was only leasehold. While adhering to red brick, Lee had amended his plans. The church had only 1,250 sittings and omitted a full-height north transept in favour of a gabled organ bay at the east end of the north aisle. An unusual feature, reflecting the local mission and a memorial to Champneys, was an external pulpit, placed on a staircase turret at the north-west corner of the nave. There was a large ‘church room’ to the south-east in which relics from the old church were displayed. The interior had ornamentally carved Bath stone dressings to naked brick surfaces (some at least were intended for painted decoration), Minton floor tiles and a ceiled wagon-vault, a form chosen for auditory reasons, ill-advisedly as the building had very poor acoustics. The old clock and bells were reset. Lee deployed thirteenth-century style details and himself designed fittings including the pulpit, lectern, font and a mosaic apse floor, executed by Burke & Co. of Regent Street. Horatio Walter Lonsdale, Lee’s brother-in-law, supplied stained-glass windows. Stone carving was by Thomas Earp of Lambeth. 28

This church was short-lived, suddenly gutted by fire on a summer’s Thursday afternoon, on 27 August 1880. Flames in the organ chamber swept up the organ pipes into the timber roof. Little more than the shell and tower survived. Kitto and Gadesden led an approach to Coope, still an MP, who undertook to use his influence to secure insurance cover of £16,800 and to stump up further rebuilding costs. The acoustical shortcomings of the destroyed interior led him to make replacement conditional on a redesign by Lee. 29 The church was rebuilt in 1881–2 on the same plan, but with a polygonal apse and an open pseudo-hammerbeam roof beneath a lower ridge which did bring acoustical success. The nave west wall was given three windows in place of two, and there were other detailed variations that favoured a style more characteristic of the fourteenth century. The interior was yet more richly sculpted than its predecessor, and this time lavishly decorated with stencilling that shows the influence of Burges. Conder was the builder and Lonsdale supervised painting and glass. 30

The Church of

St Mary Matfelon, around 1920

The Church of

St Mary Matfelon, around 1920

An alabaster reredos intended since 1878 was at last made in 1886–7 as a memorial to Coope. Carved by Earp, it represented the Last Supper and the Tree of Jesse, and stood in front of stencilled decoration of the early 1880s by Lonsdale that included large angels for the Twelve Gates of the Heavenly Jerusalem. 31

Rebuilds notwithstanding, church attendance was lower than it had been under Champneys. It was estimated in the early 1880s to be around 1,500 on Sundays, albeit in a reduced parish with an estimated population of 14,000, the main impediment being what the Rev. Arthur James Robinson called ‘the old story of indifference’. 32 Yet this was among the best attended of East London churches, with fully choral services and psalms chanted morning and evening. By 1884 Robinson’s team included two Missioners to Jews, the Rev. J. H. Bruhl and the Rev. A. Bernstein. The open-air pulpit was in regular use, and by the 1890s and well into the twentieth century special services were conducted for Jews in Hebrew and German, with sermons preached in Yiddish to congregations of up to 500. A last notable rector was the Rev. John Augustus Mayo, who in 1917 lent a cellar (possibly in the rectory) to Maria Dickin for the first People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals of the Poor. Mayo also gave the first radio sermon in 1922.33

The Church of

St Mary Matfelon in May 1941

The Church of

St Mary Matfelon in May 1941

St Mary’s Church was gutted once again, this time by fire bombs on 29 December 1940. The ruined shell of the building was cleared in 1952. 34

-

Victoria County History Middlesex: vol. 11, Stepney, Bethnal Green, 1998, pp.1–7, 13–19, 70–81: Jane Cox, Old East Enders: A History of the Tower Hamlets, 2013, p.52 ↩

-

ed. A. H. Thomas, Calendar of the Plea and Memoranda Rolls of the City of London: vol. 1, 1323–1364, 1926, pp. 208–9: G. Reginald Balleine, The Story of St Mary Matfelon, 1898, p.10: Kevin McDonnell, Medieval London Suburbs, 1978, pp.141–2: Historic England, GLHER, MLO3933 ↩

-

ed. C. J. Kitching, London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate 1548, 1980, pp.xxx–xxxi, 6 ↩

-

George H. Birch, ‘Stray notes on the Church and Parish of S. Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, old series, vol. 5, 1881, pp.514–18: LMA, Collage 35135: Richard Newcourt, Repertorium Ecclesiasticum Parochiale Londinensis, vol. 1, 1708, p.698: Balleine, p.14 ↩

-

Balleine, pp.12–13: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for Hunne ↩

-

George Hennessy, Novum repertorium ecclesiasticum parochiale Londinense, 1908, p.457: Patrick Collinson, Richard Bancroft and Elizabethan Anti-Puritanism, 2013, pp.110-11 ↩

-

ODNB for Crashawe: Balleine, p.15: Derek Morris, Whitechapel 1600–1800, 2011, p.152: TNA, PROB11/356 ↩

-

Newcourt, Repertorium, p.699: John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, vol. 2/4, 1720, p.45: Keith Lindley, ‘Whitechapel Independents and the English Revolution’ Historical Journal, vol. 41/1, 1998, pp.283–91 at p.286 ↩

-

Murray Tolmie, The triumph of the saints: the separate churches of London, 1616–49, 1977, p.76 ↩

-

London Metropolitan Archives, DL/C/344, ff.170v–72r: Lindley, loc. cit.: A. G. Matthews, Walker Revised, 1948, p. 52: A. G. Matthews, Calamy Revised, 1934, p.508: Balleine, pp.15–18 ↩

-

Newcourt, Repertorium, p.700: ODNB for John Davenant and Fuller ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/090; P93/MRY/091, pp.341–64; DL/C/345, ff. 88v, 112v; Collage 22631: Edward Hatton, A New View of London, vol. 2, 1708, p.406: Strype, p.45: Matthews, Walker Revised, p. 52: Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, London, vol. 5: East London, 1930, pp.71–2 ↩

-

Peter Guillery, ‘Suburban Models, or Calvinism and Continuity in London’s Seventeenth-Century Church Architecture’, Architectural History, vol. 48, 2005, pp.87–92: Birch, op. cit. ↩

-

Newcourt, Repertorium, p.699 ↩

-

Hatton, p. 406: Strype, p. 45: RCHM, op. cit., p.71: LMA, Collage 22632; P93/MRY1/092, pp.7,9 ↩

-

As quoted by Anne J. Kershen, Strangers, Aliens and Asians: Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields, 1666–2000, 2004, p.170. When this was quoted by G. Reginald Balleine in 1898 he added ‘how blind this prejudice was … May we learn the obvious lesson for ourselves!’, Balleine, p.22 ↩

-

The Builder, 30. Jan. 1875, p.93 ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/90: Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives, LC6854, P/MIS/330 and P10051: ODNB for Payne, Welton and Fellowes: Balleine, pp.19–25: David Hughson, London being an accurate history etc, vol. 4, 1807, p.431 ↩

-

Lambeth Palace Library, MS2690, p.10 ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/90: St James’s Chronicle, 19–22 Jan 1762: THLHLA, P100058: Balleine, pp.28–9: Morris, op. cit., p.165 ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/90: B, 30 Jan. 1875, p. 93 ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/90: Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 85/2, 1 July 1815, pp.28–9: information kindly supplied by Michael Kerney: Alexandra Wedgwood, 'Pugin's first and second wives', True Principles, vol. 3/2, summer 2005, pp. 67–9 ↩

-

The Builder, 18 March 1865, p.200; 30 Jan. 1875, p.93 ↩

-

ODNB: Balleine, pp.33–5: Lambeth Palace Library (LPL), Tait 440/433; Tait 441/457 ↩

-

THLHLA, L/SMW/A/1/1: LMA, P93/MRY1/092: Post Office Directories: Mark Girouard, The Victorian Country House, 1979, p.397 ↩

-

THLHLA, L/SMW/A/1/1: LMA, P93/MRY1/092 ↩

-

District Surveyors Returns: The Builder, 30 Jan. 1875, p.108; 24 July 1875, p.659; 23 Oct. 1875, p.962; 27 Jan. 1877, pp.89–90: Illustrated London News, 24 July 1875, p.93: The Times, 3 Feb. 1877; 1 Sept. 1880 ↩

-

LMA, P93/MRY1/092; P93/MRY1/173–4: THLHLA, LCF00550: Building News, 8 Sept. 1876: The Builder, 27 Jan. 1877, pp.89–90; 16 March 1878, pp.266–9: The Architect, 4 Aug. 1877; 15 Dec. 1877, p. 328: V&A Drawings, E2286–7-1911: RIBA Drawings Collection, PB179/23: Gordon Barnes, Stepney Churches, 1967, pp.48–53 ↩

-

THLHLA, L/SMW/A/1/1: The Times, 1 Sept. 1880, p.3; 12 Oct. 1880, p.7; 14 Oct. 1880, p.4: The Standard, 30 Aug. 1880: ILN, 4 Sept. 1880, p.248: Pictorial World, 4 Sept. 1880, p.432: Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes, 15 Oct. 1880, p.467: The Builder, 20 Nov. 1880, p.630 ↩

-

THLHLA, LCF0051: Building News, 12 May 1882: THLHLA, A. J. Robinson, A short history of the parish church of Whitechapel, 1886: V&A Drawings, E2280–2284-1911: RIBA Drawings Collection, SD65/18 ↩

-

V&A Drawings, E2285-1911 and 2288-1911: Bishopsgate Institute, E. C. Lee, A short history of the parish church of Whitechapel, 1887, pp.15–16 ↩

-

LPL, FP Jackson 2, f.513 ↩

-

LPL, Benson 25, ff.96–8: Henry Walker, Sketches of Christian work and workers, 1896: THLHLA, Parish of St Mary Whitechapel, Annual Report and Accounts, 1913, pp.32–7: ODNB sub Dickin: information kindly supplied by Dr Sharman Kadish and Howard Spencer ↩

-

LMA, P93/PAU2/044/1; GLC/AR/HB/02/375 ↩

Maddock tomb

Contributed by Survey of London on June 27, 2016

This chest tomb for the Maddock family (timber merchants on Rosemary Lane, now Royal Mint Street) is a stout early nineteenth century monument of Portland stone with a marble armorial panel, a pyramidal top and an urn finial. It remains in situ at what was the south-east part of the parish churchyard – land to its east was the rectory garden. Some other surviving gravestones were recorded in 2011. 1

-

Historic England, GLHER MLO3933: Post Office Directories ↩

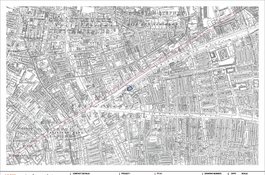

Ley Street and Queen Matilda's 12th-century Bypass

Contributed by Mark Willingale on Oct. 13, 2017

This account describes how Ley Street, the original direct Roman road through Essex, became obscure and how the Chapel of St Mary Matfelon marks the point where Queen Matilda’s 12th-century bypass departed east from the Roman road to cross the two branches of the Lea further south with two new bow-arch bridges, each with their own chapels dedicated to St Mary, and converged with the original road just beyond a new bridge over the Roding also with a new chapel dedicated to St Mary, the Hospital Chapel of St Mary the Virgin at Ilford.

Ley Street, seen on the Chapman and Andre map of 1777 and named on later maps, is a short stretch of road in Ilford that once formed part of the original Roman military road through Essex. 'Ley' is an Anglo-Saxon term for a forest clearing and Ley Street was the road through the Essex forest from Caesaromagnus via Durolitum to the ford of the Roding at Ilford, built with the technology and resources of 1st-century AD surveyors, for military use during the invasion. The Great Essex Road converged with Ley Street beside the hospital Chapel of St Mary the Virgin just above the ford of the Roding and is a later, less direct Roman route through Essex. How then did Ley Street, the original direct route through the forest, become obscure to be replaced by the less direct route of the Great Essex Road?

Rome controlled Britain for well over three centuries so there was plenty of time for new roads to develop serving the same destinations and for the original demands to make way for new patterns of connectivity and use. As the invasion advanced inland to the west and along the coast to the north the primary purpose of the roads in southern Britain changed from military to civilian use. The tactical and logistical roles of advancing the invasion inland changed to providing connectivity to the coast. Both functions depended on tidal access, which had already been developed before the invasion to support trade between Britain and Rome. The iron production of the Weald for the navy and the agricultural production of the East Coast for the Army had been strategic targets for the invasion. Once the invasion had advanced to the north beyond The Wash and west to Dorchester the estuaries of Kent and Essex including the Thames could start to be developed. Iron Age agriculture and industry already occupied the higher, well-drained land above the flood plains of the rivers, creeks and saltmarshes around the coast. Much of this estuary and coastal land had already been deforested and was above the risk of flooding. The Romans had the manpower and resources to increase agricultural production by draining and developing the flood-risk, low-lying land on the estuaries of the East Coast. The Thames Estuary with relatively low rainfall and high tides would be a good place to start. Here a dam across a tidal creek with a sluice at low tide could add a significant area of newly accessible and fertile land for agriculture requiring only a modest network of new drainage ditches, dykes and canals. Agriculture and industry developed across the Thames basin, where the busiest and safest roads became those serving the growing population that settled along the coast away from the forest. Watling Street on the south side ran close to the estuary, passing creeks and crossing tributaries on the way, so this remained the primary access route after the change from military to civilian use and the development of agriculture and industry. Ley Street on the north side ran further inland on higher ground without river access and for much of the way, from Colchester to the crossing of the River Lea, the road passed through the Essex forest. The population density and pattern of connectivity developed along the estuary rather than the military road through the forest and in time the route from Brentwood to the crossing of the Roding became busier and took precedence over the inland route from Navestock Side via Durolitum to the crossing of the Roding at Ilford. The lower route of the Great Essex Road with gentle gradients through Romford and Ilford was also better for bringing produce to market by ox and cart. The diversionary course of the road, to become known much later as the Great Essex Road passing through places like Ingatestone and Margaretting, suggests a route that evolved from subsidiary tracks between existing farmsteads as they became larger agricultural settlements during the Romano- British period. The changing alignment of the road through these settlements reflects the different alignments of earlier tracks between separate farmsteads.

The less direct Great Essex Road, composed of subsidiary Roman roads, would not have been a recognised primary road of the ancient world. Furthermore, the Great Essex Road has no Saxon name while others exist for the main military Roman roads elsewhere. This encourages the view that Ley Street was the Saxon name for the original road that has been all but lost with the loss of the original military road. With over three centuries of development across South Essex and the Thames basin there was plenty of time for the old direct military road from Colchester to the crossing of the Lea to have declined during the Roman occupation and then been neglected after the army withdrew at the beginning of the fifth century. Undefended and unrepaired the old military road with steep gradients through the Essex forest, away from the settlements and access of the estuary, would have become relatively hazardous and neglected while the diversionary but more populous estuary route continued to develop. The site of a royal hunting lodge at Havering in the 7th century indicates that the old road still existed when Essex controlled London and use was still being made of the direct route from London into the forest. A later Saxon palace at Havering, complementing one at Old Windsor to the west, also suggests that the direct road still existed, ineed without some form of direct access it is doubtful that Havering-Atte-Bower could have become the site of a royal palace serving London.

The Anglo-Saxon heptarchy, followed by the Viking invasions through the late 8th and early 9th centuries, shifted power to Wessex rendering the East Coast and Thames Estuary a frontier zone. It is probably in this period that the old direct Roman military road through Essex fell into disuse with parts becoming obscure. London itself waned as control passed from the Old Saxon settlement of Lundenvic, a western appendage outside the abandoned Roman walls, to the Danelaw of Mercia and the Vikings. It does not recover until Alfred the Great retakes London in 886 and establishes Lundenburg within the old walls in 889. The treaty of 886 between Alfred and Guthrum established the Danelaw boundary between Wessex and the Danes, following the River Lea to the Thames and then running east along the Estuary to the sea. Ermine Street from Lundenburg to Lincoln would have reached the frontier of Wessex at Ware and routes east from Lundenburg would have reached the frontier at Old Ford. The severing of routes to the east beyond the Lea would have placed emphasis on north–south connectivity at the expense of east–west connectivity within Mercia, resulting in the decline and final abandonment of the old direct Roman military road through Essex. After Alfred the Great’s son Edward the Elder had annexed Essex and East Anglia for Wessex London re-emerges as the dominant centre but from this time with a main northeast radial following the route of the Great Essex Road to Colchester.

The growth of population in the vicinity of London would contribute to the next significant change in the course of the road through Essex. The proximity of the City led to the gradual change of the Manor of Stepney from a royal hunting ground to a populated area of market gardens held by the Bishop of London for supporting the Tower of London. Similarly, the land held by Barking Abbey on the east side of the River Lea down to the Thames was developed from forest chases to abbey estates and became more settled. The population increased on both sides of the River Lea south from the line of the Roman road through Old Ford. For the growing population on the land of Barking Abbey estates the crossing of the Lea at Old Ford represented a diversionary route to the City. At the same time what had before been a point of maximum divergence of the old road, at the crossing of the Roding, from the direct bearing between Chelmsford and London via Havering-Atte-Bower and Ilford now presented the possibility of an alternative and more direct route west from Ilford to the City crossing the branches of the River Lea south of Old Ford. Events came to a head in the early 12th century when the bridges and causeway of the route through Old Ford were in a poor state of repair and a risk to the lives of travellers during flood tides. Queen Matilda, wife of Henry 1, is said to have nearly drowned during a journey to Barking Abbey and in response ordered the construction of two new stone bridges and a causeway c.1110-1118. The bridge over the wider channel made use of bow-shaped arches, the first in this part of the country, hence the name Bow Bridge and in due course the name of Stratford-by-Bow on the west bank of the River Lea. Bow Bridge was located over half a mile south of Old Ford, thereby realising the more convenient and direct route from Barking Abbey to the City, serving the growing population along the north bank of the Thames estuary.

Queen Matilda’s bypass is recorded by the route of the current main road, running some 10.9km from the Hospital Chapel of St Mary the Virgin at Ilford, by the bridge of the Roding, via Bow Bridge over the Lea to converge with the old road close to the Chapel of St Mary Matfelon, later known for the bright lime wash applied to its walls as the White Chapel. The ancient line of the Roman road through Whitechapel to Aldgate High Street can be traced along the rear property boundaries of the terraced plots fronting the northwest side of Whitechapel Road, from Durward Street, formerly Buck’s Row, across Vallance Road and Davenant Street to Greatorex Street. The frontage of Durward Street, the flank end-of-terrace wall on the west side of Vallance Road just north of the Whitechapel Road and the shallow turn and rise in the ground level on Davenant Street as it runs northwest from the Whitechapel Road all record the line of the old Roman road.

Queen Matilda gave tidal mills and land at West Ham to Barking Abbey as an endowment for maintaining the new road and bridges. This led to a dispute involving Stratford-Langthorne, a Cistercian Abbey founded in 1135 and also dedicated to St Mary, which was not settled until 1315. Accordingly, it appears that there were originally four chapels of ease each founded c.1140 and dedicated to St Mary associated with Matilda’s new road, one by the merge with the old road at Whitechapel, another at the far end near the merge with the old road beyond the bridge at Ilford, this becoming the Hospital Chapel of St Mary the Virgin, one at Bow Bridge later becoming the church of St Mary and Holy Trinity, Stratford and another at West Ham on the east side of the Lea responsible for the Channelsea River Bridge later becoming the foundation church for Stratford-Langthorne Abbey. Matilda’s new road from the City, on its approach to Ilford, chose to cross the Roding on a new bridge a little south of the old one and align itself with the Ley Street, the old road heading northeast towards Havering-Atte-Bower rather than the road to Romford, indicating the continued significance of the old royal forest road at this time.

It is notable that the chapels of ease for Queen Matilda’s bypass were aligned with the road rather than the traditional east–west axis for a church. The late 14th century Church of St Edward the Confessor at Romford is also aligned with the Great Essex Road and had replaced the old church located to the south closer to the ford of the Rom, indicating that this too had been founded to fund and manage a river crossing of the road, indeed the Great Essex Road through Romford and Brentwood may have become the main artery only after the construction of Matilda’s bypass, in due course resulting in the development of estates like Gidea Hall for Thomas Cooke, a draper in Cheapside who became Lord Mayor of London in 1462 and was appointed custodian of the forest at Havering. The old royal forest road from London across the Lea at Old Ford and on towards Hainault continued to be used into the 17th century, with Samuel Pepys recording rides into the countryside, a fashion that had been established centuries earlier. The Fairlop Fair in the 18th century, around the Fairlop Oak, an ancient tree that had a girth of thirty-six feet and cast shade over an acre of ground on Fairlop Chase in Hainault, was popular with the block and pump makers of Wapping. They journeyed to the fair via Old Ford and Woodford and returned via Ilford. Just as the route of the road through Essex had moved further south in response to a growing population along the estuary in the 2nd century so in the early 12th century the route from Ilford to the City had moved further south to serve the growing population along the estuary in the vicinity of London.

From the 13th century the imparking of country estates contributed to the diversion and fragmentation of the original route. Wanstead Park embraced south western stretches of the Roman roads to Great Dunmow and Chelmsford. Havering, Bowers and Pyrgo Parks in the southwest, Writtle and Hylands Parks in the northeast, contributed to diverting Ley Street from its original direct course. The well-surveyed military road through the Essex forest is fragmented into diversionary by-ways around imparked estates.

The forests of Epping, Hainault and Havering continued to be royal hunting grounds. A 1618 Liberty of Havering Map indicates the boundary of Havering Park following the bearing of Ley Street from Orange Tree Hill southwest to the South Gate and beyond. A tenement marked Brick Hill on the 1806 Ordnance Survey (OS) map and Havering Grange on the 19th-century OS map was known as Cely’s Place in the 16th century and held by the keeper of the gate, a post of some local significance. The gate provided an entrance from Collier Row Common to the royal hunting grounds at Havering. The line of the Roman road continued directly southwest from this gate to Ilford Bridge, following the surviving stretch of road called Ley Street. Accordingly Collier Row Common was a former purlieu of the forest and the most convenient way to reach the South Gate of the royal forest from London was along the line of the old Roman road, which defined the south-eastern purlieus of Epping, Hainault and Havering forests, passing on the way a series of gates into the forests; Forest Gate by Upton Park into Epping, Padnalls or Roselane Gate, Marks Gate and another Forest Gate at Collier Row into Hainault and finally South Gate from Collier Row Common into Havering Park. The ancient forest road, though not recognised as the original Roman road, had provided a direct route from the City to the royal hunting grounds of Essex.

Padnalls is first named in 1303 and its 16th-century buildings stood in Rose Lane before being demolished in 1937. Marks Gate was named after the manor of Marks that had the right of estovers from Hainault Forest indicating a Saxon origin of the tenement. The route of the direct Roman road had continued to provide access from London to the royal hunting grounds through to the 17th century but once the purlieus and forest fringes were enclosed the road fell into disuse. The process was hastened by the disafforestation of Hainault Forest in 1851. The trees, mainly hornbeams, were grubbed up in 1853 and Forest Road, New North Road, Romford Road and Hainault Road were laid out by 1858 superseding the old routes. Ivan Margary’s attributes of a Roman road can be found on the old route from Ilford to the summit of Broxhill at Havering- Atte-Bower but little direct evidence survives. The lack of building materials in Essex compounded by the proximity of London probably resulted in the gravel of the road being robbed for use elsewhere or used in situ as hardstanding for houses and so the line of the road is obscured by development.

The southern road through Romford and Brentwood was also diverted by imparking, for example where Gidea Hall deflected Hare Street south from the original line. The name Great Essex Road for the southern route, like the Great North Road is much later and dates from the turnpike trusts of the 17th and 18th centuries set up by Parliament to raise tolls for the upkeep of the principal roads. The turnpike trusts fell into decline with the rise of the railways in the 19th century and were abolished in 1888 when their powers were handed by Act of Parliament to the Local Authorities. The Ordnance Survey maps from the first edition of 1806 through the 19th and 20th centuries first helped to clarify the routes of Roman roads and then started identifying archaeological and historical sites. Through them the Great Essex Road became identified as the primary Roman road through Essex. Only with the recent, online Historic Environment Records and the tools of Google Earth can the traces of Ley Street, the original direct military road through Essex be re- established.

Love In An English Republic

Contributed by redcoat on June 22, 2017

My Birmingham family had no desire to go to London so neither did I, until I followed my maternal Clarke pedigree via wifi in Australia. I've been digging deep into the working and middling sort of ancestors for years, making full use of the global sharing of knowledge.

My husband and I emigrated with our families when we were 14 years old and both ignorant of the English Civil Wars, but drilled in the Tudors, so my explorations in 17th-century London have been electrifying. With imagination sparking I have a novel in progress I call Providence, or Love in an English Republic.

According to the Stepney Parish Church registers, St. Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel was where Hugh Cannaday, a mariner/roper, married Thomasine Bond on January 13, 1631 (my 13x great grandparents).

Two months later, daughter Thomasine Cannaday was born in Gun Alley, Wapping, followed by Tabitha and three sons. Unlike her siblings, Thomasine survived, fell in love with John Clark and followed in his footsteps, literally as a Redcoat.

She followed her heart and her God, to receive her '15 minutes of fame' in a ballad about her time as a cross-dressing military drummer! At some point I will have to tread my way to the former church burial ground where she was buried: 5th March 1690 ~ a woman from Well Close in Well Street.

The famous Woman-Drummer

Or the valiant proceedings of a Maid which was in love with a Souldier,

and how she went with him to the wars, and also of many brave actions that she

performed after he had made her his wife, shal here be exprest in this ensuing

Ditty. to the tune af wet and weary.

OF a Maiden that was deep in love

with a Souldier brave and bold sir,

Ile tel you here as true a tale

as ever hath been told sir:

And what brave actions she performd

after she was his wife sir.

And how she did behave her selfe

to save her husbands life sir:

She marcht with him in wet and dry,

in Winter and in Summer,

For he was then a Musketier,

and she became a Drummer.

When first this couple fell in love,

a bargain she did make sir,

That when that he had need of her

she would not him forsake sir:

And so they went for two Comrades

most lovingly together,

And plaid their parts most actively,

like two Birds of one feather:

she marcht with him in wet and dry,

in winter, etc.

She had got mans apparrel on,

gay doublet and brave hose sir,

And manfuly she beat her Drum,

her enemies to oppose sir:

And she was daintily bedeckt,

acording to her Colours,

And she was like a man indeed,

just to great Mars his followers:

she marcht with him in wet and dry, etc.

They have been both in Ireland,

in Spain and famous France sir,

where lustily she beat her Drum,

her honour to advance sir.

Whilst Canons roard and Bullets flye,

as thick as hail from Sky sir,

She never feard her forraign Foes

when her Comrade was nigh sir;

She stood the brunts in heat and cold,

in winter and in summer,

Her husband was a Muskettier,

and she was then a Drummer.

In every place where she did come,

she shewd herself so valiant,

And few men might, compare with her,

her actions were so gallant:

She manage could her sword full well,

and to advance a pike sir;

But for the beating of a Drum,

you seldome saw the like sir:

In frost and snow, in wet and dry,

in winter and in summer,

Her husband was a Muskettier,

and she a famous Drummer.

She beat with three men at one time,

and won of them a wager,

And had not one strange chance befell,

she should have been Drummajor:

Her belly it began to swell

and she grew plum and jolly

But she usd all the means she could,

whereby to hide her folly:

She marcht by day and watcht by night,

in winter and in summer,

And still they took her for a man,

she was so stout a Drummer.

In company she would merry be,

and sometimes sing a song sir,

And take Todacco oftentimes,

and drink strong Beer among sir:

If any one had angred her,

or done her any evill,

Sheed quickly make them for to know

they were better crosse the Devil:

Near Tower-hill sho quartered was

in famous London Citie,

But more strange newes I have to tell

before I end my Ditty.

For she was grown so big with child,

which made her fellows wonder,

And in a short time after that,

poor soul she fell asunder:

But when her painful hour approacht,

I doe not lie nor flatter,

The women cut her Codpeece point,

to see what was the matter.

But to be brief, it came to passe,

as I must tell you truly,

She was delivered of a son

the sixteenth day of July:

The women all were kind to her

whilst that she was in labour,

Because she was a Souldiers wife,

they shewd to her much favour:

They [f]urnisht her with every thing,

as [m]eat and drink and clothing,

For child-bed linnen and the like,

they let her want for nothing:

Her husband was a Muskettier,

and she a lusty Drummer,

It seems they soundly plaid their parts

in winter and in Summer.

Let no man nor no woman think

that she hath been dishonest,

But what she did was done in love,

as she before had promist.

To keep her husband comany,

the truth of all was so sir,

And pleasure him both day and night

where ever they did go sir:

Her husband was a Musketier,

and she a famous Drummer,

It seems they plyd their businesse well

in winter and in summer.

You Maidens all that hear this Song,

consider what is told here.

Concerning of this woman kind,

that dearly lovd a Souldier:

If you with Souldiers be in love,

I wish you to be loyal,

For they to you wil faithful prove,

if you put them to the trial:

Her husband was a Musketier,

and she a famous Drummer, etc.

For love is such a powerful thing,

if it be rightly given,

There cannot be a better gift

under the ropes of Heaven;

So now brave Souldiers all adieu,

remember what is spoken,

Come buy my songs and send them to

your Sweet-hearts for a token:

Her husband was a Musketier,

and she a warlike Drummer,

I would that I had such a Mate,

to walk with me this Summer.

The Church of St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel, in May 1941

Contributed by Historic England

Altab Ali Park

Contributed by Judit Ferencz

The Church of St Mary Matfelon, interior view looking east in 1888

Contributed by Historic England

The Church of St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel, in May 1941

Contributed by Historic England

Carved panel of 1714 from west gallery of the Church of St Mary Matfelon, in St Botolph Aldgate

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Altab Ali Park from the north-west in April 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Hoardings outside the Royal London Hospital showing church c.1755

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Former churchyard wall, Whitechapel Road, summer 2018

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Mary Matfelon, c. 1920

Contributed by Survey of London

Altab Ali Park, northern section from the west in April 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Altab Ali Day

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Martyrs Day/International Mother Language Day

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Altab Ali

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Altab Ali Day 2015

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Altab Ali Day 2016

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Poster publicising unveiling of Arch, 1989

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

Altab Ali Park

Contributed by Lucy Millson-Watkins

Altab Ali Park

Contributed by Lucy Millson-Watkins

Altab Ali Park

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Gateway at north-west corner of Altab Ali Park from inside the park, April 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Altab Ali Day 2017

Contributed by AnsarAhmedUllah

St Mary Matfelon from the north-west around 1910

Contributed by Survey of London

Altab Ali Park from the south-east in 2021

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Roman road through Whitechapel

Contributed by Mark Willingale

Unveiling the war memorial at St Mary Matfelon, 1917

Contributed by Aileen Reid on Sept. 20, 2016

Altab Ali Park in 2009 before relandscaping in 2011

from YouTube - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cApAoCW37G8. This amateur film, showing Altab Ali Park before it was relandscaped in 2011, has a voiceover reflecting the filmmaker's interest in the Jack the Ripper murders

Contributed by Aileen Reid on Sept. 12, 2016