Redeveloping the public lavatories on Whitechapel Road

Contributed by Survey of London on April 30, 2018

Harun Quadi settled in the East End in the early 1980, having originated in Comilla, Bangladesh. He describes how he acquired and developed the former below-ground public lavatories at 199A Whitechapel Road, and his plans for their redevelopment.

"I came in this country in 1973 [from Chittagong], I was a junior engineer for United Steamship Company, and that company sent me for further education in South Shields and in London.

My home country is Comilla but I studied at Chittagong. I studied at Marine Academy in Chittagong, from there I finished my basic marine training then I was employed by Cunard Steamship Company in London.

I finished my training as marine engineer. Two years training in Marine Academy Chittagong, and after the training then I had the apprenticeship for two years in a workshop, marine workshop. Then I was employed as a junior engineer in Cunard Steamship Company, London. Then Cunard Steamship Company, I worked four years with that company they sent me for a higher education as a marine engineer. I did my Marine engineer class one-two-three-four and chief engineer, in South Shields and in London. 1978 to '84 I completed my education.

I lived in North London first, I was there for two years and after that I bought a house in auction in 23 Casson Street, London, E1 [in 1982]. That was a derelict house, I bought that house because I thought I'm an engineer, I could repair the house and make it for my own living and business.

I bought it for £55,400 and it is a five storied building, it was derelict and about ten rooms was there, only one toilet at that time. It was cold and it was just only birds living there. As an engineer I got confidence and I employed one or two builders and I worked with them as well, I made that whole house habitable. That was my first venture, that was ten rooms and five floors. I lived in one of the floors and rented out all the four flats, four rooms for flats. They're not self-contained flats but it was like flats.

I've owned [Bengal Cuisine] for the last 25 years, and then I bought two [derelict] properties in 1993 [one on Whitechapel Road and one on Commercial Street] which were [both former public] toilets.

Finding a business opportunity

In 1993, I was looking for some kind of development project and I thought that I could develop better than anybody else because of my engineering experience. Then I saw these two toilets were misused, they are full of rubbish, they are misused and say, it was in the market but nobody thought the idea of what it can be.

Most of the people thought it could be storage, it could be toilet again but I got the information from the council, at the same time I studied it, I thought it could be business premises.

[I didn’t know] what business but I [realised that] these two premises are in a very important location, I could [develop] them into some businesses then definitely the price will be improved, the property will be improved.

199A [Whitechapel Road] at that time, it was only a toilet, there was no address on it. We applied for the address, we got the address which is 199A Whitechapel Road.

I bought it for £15,500. There was many other people thinking of buying it, but the point is that they thought only to make it as a storage and they would not go more than more than the tag price but I thought that if the price went up enough, I would have gone more.

Above-ground there was only railings there, [and] two entrances, one in each end.[It] was not being used at the time. Probably, at 1993 it [had been] unused for ten years probably, and it was a congregation place for drunk and addicts there. The whole place was full of rubbish, like cans and garbages, market garbages, and drunk population used to be there.

People were very frightened of going there to do something. Even after I got the planning permission, I started doing cleaning it, cleaning it up and they were getting together the drunk people there, saying that, "You cannot do anything here, this is our place and we are claiming it and we'll stay here and we'll not go anywhere", but I just took things easily and slow and steady. I convince them that they have to move.

Developing the site

I cleared it up and after that I applied for the planning permission. The planning permission to [convert it to] a business premises [not to build] was not easy. [Then], we got into [an] idea that we could make one story building on the ground floor. I applied for TFL permission, then we got a planning permission also. It could be 1997-8. Until that time, it was empty.

[The architects were] Clements & Porter [who were], at that time, very young, enthusiastic architects in this area. They were looking for a job and they said that, "This is wonderful project, I'll take it." I felt good that they're taking the venture with me.

[A] One-story building was a challenge. We [had] to convince the local authorities, the councilors, the people. There was investigation [as to] whether it is feasible because it is middle of the pavement. It is not in easy place, middle of the pavement very unusual planning permission also.

[The planners were] difficult to persuade. First, our next-door neighbour was saying, "That is right in front of my shop then it is going to shade me". Then I got all the information what is the regulation of the shading. We found out that we're 20 feet away, minimum 20 feet away from the other building. We have taken all the light readings also. Those readings, even I may call it tall building, it doesn't shade according to the planning regulation. At the same time to be more sympathetic towards our neighbour we made it glazing so that one side to another side it is transparent also. That problem we overcome by rules.

We [gained] planning permission A3 for restaurant. Basement it was toilet, and that from the toilet we have clear it up, and then basement was part of the restaurant kitchen, and the ventilation part, down with the kitchen is elementary, so fan was there. [In] the basement, this little part my wife made it with a little [beauty] parlour there.

Building was not very difficult. We had an Indian Sikh builder and our architect was Clements & Porter. She was good in supervision the building also reasonably good. It was blocks. Most of them are breeze blocks. I think breeze blocks looks very temporary. We cladded with tiles, black and white tiles. We put black and white tiles which was resembling to the next building to the building. I found out later that black and white tile was not a good idea, because black and white tile still [makes it look like a] toilet [while] we are going to make a restaurant, so people probably might mistake with the toilet.

I think I completed the building work over 1998. Because restaurant business was reasonably good, but again, as a restaurant, we put a service restaurant. Service restaurant was not very good there, that was a market store, all around, so other peoples are there. That was not very suitable for a service and more expensive restaurant. It could've been very cheap and fast food restaurant could've done a lot of better.

[The construction] cost about £200,000. We got a grant of £60,000. That's really boosted, helped to build the building.

The accident

[In] about 2002 or 3 [the restaurant] met an accident. At night some coach banged on it. The building was just partially damaged but council came down they said, "No, it is not safe so we will take take it down". I was not in the country, I was abroad and in the meantime this accident happened.

It was a shock. I saw the pictures that were sent to me. I hurried to flied back to London. What to say? I couldn't do much. The council put barriers all around and after the council slowly cleared all the ground and barriers still remained, but then that barrier remained about four-five years. People started [chuckles] throwing rubbish inside the barrier because of the market. We had a hard time to clear all this rubbish almost every day.

New design ideas

Then my wife went to architect MacCormac. She got the planning permission, old planning permission back. They were reputed architect also. They made a very good restaurant design again there in 2004 or 5. After it was cleared. They got planning permission easily this time just because it was a restaurant before. Very similar type of building, but better design.

Now, I forgot to say I [thought that I] could do something better. I don't want to just keep on running a restaurant. It's a beautiful site, good site. It could be beautiful for any other things. I want to make, basically, a good building. That building, it could be restaurant, it could be any other businesses, if some more enthusiastic or some more energetic company comes, a resourceful company comes, they can use it in a very much better way than me.

I hired an architect, Neil Bell from Sweden. He designed us 14 storied building there. He said that we can make a Japanese board hotel. 50 rooms, Japanese Board Hotel. I was very excited about it. Then I discussed with various planners. I went to the planning office with my architect also. They said they didn't know, 14-storied building it could be very difficult. He was saying that, "Look, it is the gateway to the city", and the Council Office says they thought that, "Gateway? No, it's not the gateway".

Then when we saw that we cannot do a 14-storied building, it was only imagination. Looked very, very well. I gathered some sponsors also to build it up. Whatever the money cost, we could have raised it. Then Neil Bell was saying that why not do something smaller than the building next door building. [There are] some five six-storied buildings, we [wanted to go] as high as them.

We are now trying to make around one, one and a half, two-storied building, so that [the] planners like it.”

Harun Quadi was interviewed by Shahed Saleem on the 17th January 2018 at No.12 Brick Lane

Walking along Whitechapel Road to the Waste, c. 1960

Contributed by patricia on July 5, 2017

To walk to Whitechapel Road, we would go down Greatorex Street, passing the bomb sites on the street, the little houses and the factories opposite Great Garden Street, turn left at the corner of Whitechapel Road, and pass by the Gas Shop, a shoe repair shop next door, Adolph Cohen Hair stylist (where Vidal Sassoon got his start), then Dolcis shoes and continued walking, past Davenant School, where my husband went to school, past Vallance Road, and go shopping along the Waste. I got my first record player plus three records at Wally for Wireless next to Whitechapel Station. There was always music playing along the Waste. Barrow boys calling out the price of fruit and veg. In the winter they had fires going to keep warm and to roast chestnuts plus lights everywhere when it got dark early. You could also get to Whitechapel High Street by going through Old Montague Street, but I never liked going that way as the houses were old and dilapidated. It was a bit scary as a child.

Childhood memories of the Taja restaurant

Contributed by Survey of London on May 15, 2018

Tanha Quadi remembers growing up with the Taja restaurant at 199A Whitechapel Road that was owned and managed by her parents in the early 2000s.

"It was somewhere we used to go everyday, we’d find something new to explore and get up to so much mischief. The place had two floors and a small loft space that we endlessly tried to reach into (we knew there were old Christmas crackers up there). It was a place of joy and happiness.

The building was bought when my mother and father were still together and they jointly ran a restaurant called ‘Taja’ that served traditional Indian cuisine. There used to be a lot of anti-social behaviour around the restaurant as there was a lot of homelessness on Whitechapel Road, along with the rough sleepers there were two hostels close to the premises as well. I remember mum feeding them to keep them under control, it did work.

As time went on my parents began going through a divorce and things became a little more tricky, the building was split with my father running the restaurant upstairs and my mother running a salon downstairs. Both ran successfully and I even recall ‘Rachel’ from S Club 7 coming to do her eyebrows at the salon (apparently we did the best eyebrows in town), an exciting day for us indeed.

Things were not always smooth sailing; as you can imagine when emotions and a business are present, nonetheless me and my brother were very much in our own world oblivious to life’s problems. We went to Kobi Nazrul Primary School which was down the road and we’d get picked up by my uncle and dropped at ‘Taja’.

Mum would be busy almost all the time so we had full rein to go wild, as we did. Bothering customers and creating ‘potions’ in the kitchen and salon. I remember customers at the restaurant complaining, saying that they had come to an Indian restaurant not a disco as the four of us would play ‘The Venga boys’ CD (that we were obsessed with) on full volume and dance and sing.

I remember quite randomly loving the chairs of the restaurant. They were thin wooden circular topped with royal blue seats and thin metal arm rails. I used to think they were so cool.

I remember finding out the building got hit in the middle of the night and my mum rushed out of the house. A coach drove straight into the building, no passengers were hurt but I remember the driver being in a coma. I don’t know what happened to him. There was a lot of mainstream news coverage of the crash.

It was a shock and we saw the devastation the next day after school. It was surreal and horrible to see. One minute it was there and the next it was gone. The downstairs was sealed off and the top structure was demolished. I remember a fireman bringing my sister's bike out from the rubble and her screaming to go get it, that’s all I remember of the day.

It was really strange. The downstairs was such a big part of our lives. The staircase was my favourite. It was metal and winded down all the way. We use to light candles all the way down to the salon and I would spend ages playing with the candle wax sitting on the stairs (and occasionally burning my hair from bending over the candles).

It feels weird to walk past and know that it’s still there. As it was. No one knows that when passing by; there’s a beautiful staircase and the ruins of a salon and a kitchen under the road. I would love to see how it looks now.

At the time the salon was also our only source of income, not only for us but for the five or so staff we hired. Lives for many that day changed.

I loved that place. We grew up in the building. Times change, I don’t know how things would be if it was still standing."

Impressions of Whitechapel

Contributed by Survey of London on April 4, 2018

On the 16th March 2018 the Survey of London collaborated with design consultants make:good and the Whitechapel Gallery in holding a workshop with GCSE students from Swanlea School, on Brady Street. One of the outcomes was the first responses from the students when thinking about Whitechapel. Their comments are posted below, and a fuller description of the workshop is on our blog (tab at top of page).

"Whitechapel reminds me of things that I do everyday in school and hanging out with my friends after school around the Sainsburys". (Rukshana Akhtar)

"I think of Whitechapel as a very busy place. There are too many people during the day and in the afternoon it is very busy". (Mohammed Abu Sufian)

"I have crystal clear memories of the crowded place, Whitechapel. Every time I walk by, the concentrated smell of various things hits my face just like a brutal punch. The noises of sirens, people and market stall people is aching". (Tamim Mazum Der)

"My memories of Whitechapel lie within helping my mother doing grocery shopping. While she talks about her day with her friends, I just think about going home and wanting to play playstation 3". (Mohammed Mustakin)

"Whitechapel reminds me of how much it has changed. There used to be a McDonalds and a Pizza Hut". (Kamran Miah)

"What I remember most about Whitechapel is how they moved the station to another place, and how after they regenerated the area around it. For example, they made the overall image of the surrounding area nicer, built a new pathway and stairs and new shops like costa". (Aksar Islam)

"I have lived in Whitechapel since birth, I have a wonderful memory of and childhood of Whitechapel". (Zahra Sarfraz)

"Whitechapel reminds me of the effort I need to put in to go to school, especially when living far away". (Nuna Irdina)

"When I think about Whitechapel, I think about the old Royal London Hospital and why they stop using it". (Md Saidur Rahman)

"Whitechapel reminds me of my first day of school. It was raining and my whole uniform was soaked. But I loved how the clouds were looking and dripping of the rain". (Eusra Mahadi)

"Whitechapel reminds me of something that I go past every day which is the Booth Memorial statue. It is interesting how it is still in the same condition as it was once buit. It also shows how other people pay tribute to others". (Adnan Alam)

"The colour combination of the market reminds me of a rainbow, before it becomes 'overpopulated'. But I think that it is still great". (Hassan Ahmed)

"Whitechapel used to be about tradition and cultures that felt close to the people living around but now is having a business meaning to it as it becomes more posh and rich getting rid of the culture." (Sofin Islam)

Working in Whitechapel's restaurants

Contributed by Survey of London on April 17, 2018

Rehana Islam Shumi came to the UK in 1998, and for the past 20 years she has been working as a chef in restaurants in East London. One of these restaurants was ‘Taja’, located at 199A Whitechapel Road until it closed. In her interview she describes her time at the restaurant and the surrounding area.

“I was born in Bangladesh, that is where I was brought up, that is where I did my schooling, and then I came to London in 1998. I came from Bangladesh for political reasons. There were political problems happening at the time and for that reason I came to London. I came on my own [and] when I first arrived I stayed in North London, I came to stay with a friend; I didn’t really have anyone here so I lived with my friend.

She [was also from Bangladesh and] had come to London a long time ago, I knew her mother in Bangladesh, so her mother gave me her number, so when I arrived I contacted her and with her help I got around and got to know other people.

Because of the politics [in Bangladesh], this was the way that people had to leave from Bangladesh, so wherever I had ended up I thought I would be better and safe.

The day I arrived to London, the following day I went to the Home Office to seek asylum. After seeking asylum, after that in North London Haringey council gave me food vouchers and a house too, a room they gave, that’s how slowly slowly I got on my own feet.

..[In North London] I was working at a solicitors' firm, I would clean the office, keep it tidy and do some administration also, this is the kind of stuff I did…

I didn’t know there was such a big Bengali community in London at the time, so after one year of living here I found out about the Bengalis in East London. It was a huge community, so I came over and started talking to people. Then a restaurant owner on Brick Lane helped me out a lot.

It was Salik’s Restaurant, Salik’s Café, I used to help them out there, used to do a few odd jobs for them, that is when the council also stopped my food vouchers and I also lost my house, so I would go there, do some jobs for them and eat with them, so slowly slowly that is how I was living at the time. [That restaurant] is no longer there.

Someone in South London gave me a place to stay, I still live there to this day. I worked seven days a week [in Whitechapel], I stayed the whole day, from 8am to 10pm, basically lived here, just basically went to sleep a little in South London.

The Brick Lane area, to me it doesn’t seem like it had developed that much, the lane still has some of its old features. I’ve been working on Brick Lane from 1999 onwards. I have been associated with them, worked for them, ate and stayed. I didn’t get paid much at all, but staying and eating did not have a cost. All that I needed at the time, I received from them. That’s how it was.

Many things have changed since before, a lot of development, Brick Lane is a lot more beautiful than it was before. When I first came the Lane was not that beautiful, as it is now. And also there were people back then, but not as much as there are now, now there are many, many people.

I mean, I never really thought anything of [being a woman in a predominantly male workplace]. I worked just as anyone else.

Well, what [was] I supposed to do? I didn’t have any other way… and for that reason I learnt how to be a chef, went to many different restaurants, shadowed many different chefs, and now through experience I am a very good chef, but I would not say I am successful yet... But still I am so proud of Brick Lane, I have been here for so many years, my livelihood has been here, I love it, East London, Whitechapel, Mile End, Stepney Green, these areas are well known to me. And the spaces are a lot nicer than what they used to be, I like it a lot.

[I like the area] now more, and before there weren’t that many Bengali ladies around. Now from Bangladesh you get a lot of students, there [are] loads of Bengalis now, tons, we have a lot of cultural parties, we get involved in politics. I have become acquainted with loads of ladies, we have the ‘mela’ [festival] too, lots of things happen.

Our Bengali new year is celebrated here in London, the council has facilitated this for us, here thousands of people get together and loads of ladies too, that enjoyment that we would have during this time in Bangladesh, this is mirrored over here, we have the same kind of enjoyment, in East London, this is where the fun is at, nowhere else. That’s why we as Bengalis are very proud of the area. Bengalis have really made the area. Even if it is an English country, this area feels like a Bengali area. The Bengalis have increased, yeah they haven’t reduced. There’s so many in this area.

Working at Taja

There was a restaurant in Whitechapel, right in the middle of Whitechapel, between New Road and Vallance Road; on the side there was a restaurant called Taja. There, there was a woman who was the owner, this woman took me over to the restaurant.

I got in contact with her as she came into a restaurant that I was working at on Brick Lane as a chef one day, she came to get some food and we started talking, then she told me she is opening a restaurant, will I come over, then she used to take a lot of care of me, she was lovely, she treated me just like a sister, Even when she couldn’t give me work, I would still forcefully stay with her, Yes I would do that, then she was really good, I really liked the restaurant, the food was good Bengali food, because I was good at making this kind of food I would go and help her out.

The building upstairs was really decorated, it was really nice, there were seats, maybe seating around fifty, people would sit and eat, and downstairs was the kitchen, the owner also had a beauty parlour downstairs. It was really nice, I really liked it. It was quite surprising, it would really catch your eyes, the building the restaurant, it was striking. Then there was a horrible disaster and the building was destroyed, through an accident. It was a night time, I was working there at the time too, I went home around 11pm, and the incident took place around 2.30am. After that the place was ruined, I felt really bad at that time.

Whitechapel Road has had a lot of changes since then, the road was very narrow, in the last two years or so have they made it wider and the road looks so much better.

Now I am still working in restaurants, I pass my time working on Brick Lane, as I am the only one I think as a woman that works as a chef on Brick Lane. All those around me are men, I don’t see anyone like myself who takes on this responsibility... I have been here for about 20 years… If they give it to me, I want to try and open my own restaurant, all with women

Right now I am very politically involved, with the main party for the UK BNP [Bangladesh National Party]. I am the general secretary for the women’s division and British women’s senior vice president. I am also part of the citizens' movement, so I do a lot of social work and I know many within Bengali media. I am well acquainted with them all. That’s all, really.”

Rehana Islam Shumi was in conversation with Tanha Quadi on the 27th February 2018. This interview was conducted in Bengali, and this transcript has been translated and lightly edited for print.

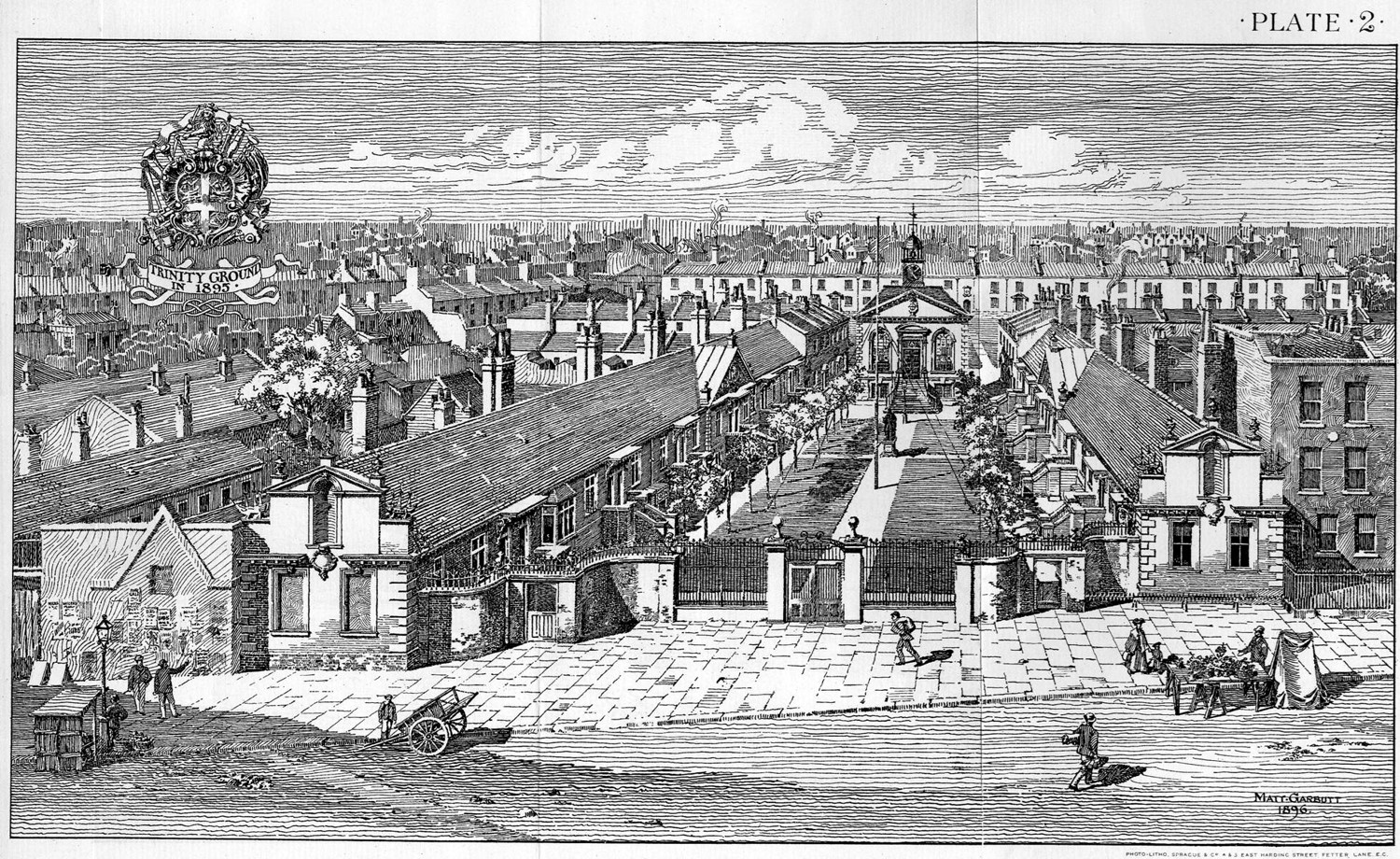

Trinity Hospital, showing

use of the Waste by costermongers in the 1890s (from C. R. Ashbee, 'The

Trinity Hospital in Mile End: An Object Lesson in National History', 1896)

Trinity Hospital, showing

use of the Waste by costermongers in the 1890s (from C. R. Ashbee, 'The

Trinity Hospital in Mile End: An Object Lesson in National History', 1896)

.jpg.265x175_q85_crop-0%2C0.jpg)