The Royal London Hospital

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

The Royal London Hospital is one of the capital’s largest teaching hospitals,

serving a diverse population of 2.6 million in east London. The institution

was founded in 1740 as the first charitable infirmary on the east side of

London, intended to offer relief to merchant sailors and labourers, and

supported largely by voluntary contributions and donations from its foundation

until the establishment of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948. The

hospital has been an important landmark on the south side of Whitechapel Road

since it transferred to this site in 1757, when it was surrounded by open

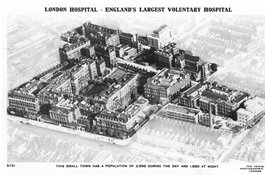

fields. Over the next 250 years the hospital expanded gradually to become a

sprawling healthcare complex, due to local population growth and advances in

medicine and surgery. Its piecemeal evolution was also a reflection of

uncertain finances and fundraising efforts. From the late nineteenth century,

the hospital spilled into purpose-built detached specialized blocks and a

cluster of nurses’ homes was constructed in its immediate vicinity. The

footprint of the hospital has recently contracted for the first time in its

history, with its transferral to a modern tower block to the south of its

historic base. Overlooked by its towering successor, the retained former

hospital is set to be refurbished and extended to provide a new civic centre

for Tower Hamlets Council. Along with its long and continuing significance to

the public life of the area, the Royal London Hospital is celebrated for its

association with brilliant minds and significant individuals, such as the

pioneering surgeon Henry Souttar and the heroic nurse Edith Cavell. A darker

fascination endures around the hospital’s faint connection with Jack the

Ripper and its provision of a permanent and compassionate home for Joseph

Merrick, known popularly as ‘the Elephant Man’.

Early History, 1740–1778

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

Foundation

The Royal London Hospital traces its beginnings to September 1740, when seven

men met at a tavern in Cheapside to consider plans for establishing a new

infirmary. Shute Adams, druggist, Josiah Cole, apothecary, John Harrison,

surgeon, and Richard Sclater, were affiliated with the medical profession,

while Fotherley Baker, lawyer, John Snee, girdler, and George Potter were

associated with commerce and the law. At its inception, the hospital joined a

rich thread of charitable infirmaries in the capital, including St Thomas’s

and Guy’s in Southwark, St Bartholomew’s and Bethlehem in the City, and St

George’s at Hyde Park Corner. Its founders possessed a common concern for the

care of labourers and merchant seamen, along with their wives and children.

There was not yet a hospital to serve the east of London and its rapidly

growing population, mostly dependent on employment in industry and trade

connected with factories, sugar refineries and the port. A fund was raised to

establish a new hospital that would offer assistance without charge to its

patients. At the first official meeting of the founders, Harrison presented a

five-year lease of a house in Featherstone Street, Moorgate, taken for the new

infirmary. A motion to establish the charity met with unanimous approval. No

time was wasted in acting upon this resolution and in November 1740 the

hospital opened its doors to patients as the London Infirmary. The charity

received patients sent by its governors, as well as people who arrived without

a recommendation. The house contained about thirty beds for inpatients and

cases were also taken as outpatients, but incurables were not admitted.

Harrison, Cole and Dr John Andree, a physician who had trained in Reims,

attended on a daily basis without pay as surgeon, apothecary and physician.

These honorary posts were supported by salaried staff, including a matron, a

porter, nurses, and night watches.

Within six months of its foundation, plans were afoot for the infirmary to

‘take a larger house in a more convenient situation’. By April 1741, a

house was secured on the south side of Prescot Street, Goodman’s Fields. This

location was judged to better serve the charitable interests of the hospital

due to its proximity to the dwellings of both Spitalfields labourers (who were

overwhelmingly weavers) and merchant sailors near the Thames, and its distance

from any other hospital. A lease of the house was agreed for a term of just 3½

years. The infirmary moved the following month and opened with room for about

forty beds. A shop was also purchased in nearby Alie Street for an

apothecary’s store and, in 1742, another house was taken on Prescot Street to

isolate patients with venereal disease.

Need for enlargement

By 1743, the expiration of the lease was looming and its renewal under

consideration. Plans for the provision of a new building for the hospital were

sparked by the intervention of Isaac Maddox, Bishop of Worcester, who was

invited to deliver a sermon at the charity’s annual anniversary feast in April

1744. The matter of the lease was still unresolved and uncertainty surrounding

the hospital’s future in Prescot Street probably struck a chord with the

bishop’s philanthropic interests. From modest origins as an orphan, Maddox

rose to become a prominent and charismatic voice in support of charitable

hospitals, including the St Pancras Smallpox Hospital and Worcester County

Infirmary. He is commemorated by a funerary monument in Worcester Cathedral

which bears a depiction of the Good Samaritan and an epitaph that remembers

him as an ‘Institutor of Infirmaries’. In his sermon, the bishop argued

that the infirmary was overcrowded and inadequate: ‘admittance is impossible;

the scanty building waits your necessary assistance to enlarge its

bounds’. This declaration spurred the charity into action; a donation of

twenty pounds from the bishop was allocated for the enlargement of the

hospital and a fund opened for a new building.

An agreement with Richard Alie, landlord at Prescot Street, satisfied the

immediate need for enlargement. The house was re-taken on a lease of twenty-

one years from Christmas 1744, along with three adjoining houses and a shed at

the end of the garden. An extensive programme of repairs and improvements

followed which, by 1745, had reached such an intensity that the supervision of

a surveyor was required. Isaac Ware was appointed to this honorary role in

return for compensation of his travel expenses. Ware was in a secure position

to perform the duties of hospital surveyor, having been the architect of the

conversion of Lanesborough House at Hyde Park Corner into St George’s

Hospital.

An inspection of the houses by a committee of governors, including surgeon

Harrison, initiated plans to repair or rebuild the shed. It became apparent

that it was too dilapidated for renovation and that a new building was

required to accommodate a range of functions, including a waiting room, a

chapel, a laundry, a distillery, a laboratory, a mortuary, and a cold bath.

Ware was instructed to prepare designs and Joel Johnson and Robert Taylor were

contracted as builders in partnership. The building was completed in 1747, yet

the House Committee was troubled by reports that the cold bath was poorly

finished and complaints from neighbouring residents about a cesspool emptying

into Chamber Street. By June, Ware judged it ‘impossible’ to continue as

surveyor due to ‘the distance of his abode, and the multiplicity of his other

business’. James Steer was invited to take his place. The committee may

have hoped to benefit from Steer’s experience as surveyor at Guy’s Hospital,

where he designed its east wing in 1738–9. Yet Steer’s involvement was

fleeting: like his predecessor, he was distracted from his honorary post by

fee-paying ‘business’. Boulton Mainwaring, surveyor and son of a Staffordshire

surgeon, was then invited to assess the cold bath and sanitary arrangements

and by August 1747 was acting as surveyor. This was the beginning of a long

tenure as hospital surveyor; Mainwaring was to play a pivotal role in securing

the site for a new building on Whitechapel Road and designing the hospital’s

first purpose-built home.

Search for a site

Consideration of the need to secure a permanent home for the hospital

continued after the building works of 1746–7. While these measures had

improved conditions at the infirmary, they did not guarantee a long-term

solution to the problem of overcrowding. The refusal of a lease extension

struck a fatal blow to any plans to remain at Prescot Street. In June 1746,

Richard Leman (formerly known as Alie), confined to his country estate with

gout, had declined to grant an additional term. This outlook, coupled with

concern that the houses would be ‘too old and ruinous to continue in longer’,

prompted the House Committee to revisit the Bishop of Worcester’s campaign for

a new building. In December 1747 a committee of governors was appointed

to secure a suitable piece of ground on the east side of London, close enough

to the City for the convenience of its governors, physicians and

surgeons.

The sub-committee was ordered to proceed in its search with ‘great management,

secrecy and expedition’. They had not met with any success by April 1748,

and the task of finding a site was delegated to Mainwaring. In June, he

reported that the only suitable site was that ‘commonly known by the Name of

White Chappel Mount and the Mount Field’. Situated on the south side of

Whitechapel Road, an arterial road which offered a direct route to and from

the City, the largely open site was well-positioned to answer the charitable

aims of the hospital, being near to the workplaces and dwellings of its

nominal patients and at a distance from any other hospital. It was in the

possession of Samuel Worrall, most likely the carpenter and builder prominent

in development in Spitalfields between 1720 and 1750. He offered to part with

his interest in the land in Whitechapel, which he held on a sixty-one-year

lease from the City, for £750. Mainwaring intended offering about £600 and

thought a longer term could be obtained easily as the City held the land from

the Wentworth estate for a term of 500 years. Worrall insisted that his high

price would only cover the expense already incurred of some new buildings on

the land.

The hospital began negotiations with Worrall, specifying an interest in the

undeveloped land. In October 1748, newspaper reports stated that the hospital

had taken a piece of ground and was proceeding to erect a building, when the

matter was actually far from settled. The hospital was still in negotiations

with Worrall, and considering other properties. These included sites in Lower

East Smithfield, Leadenhall Street, Houndsditch and Bethnal Green, along with

the adaptation of London House in Aldersgate Street. Greater consideration was

given to two other sites in Whitechapel, yet one was too expensive and the

other objectionably close to a white-lead works. In August 1749, the situation

was still uncertain and Worrall now offered his land for the higher price of

£800, which was received as ‘very improper’. William Myre, a governor, was

asked to make an appeal to his acquaintance Lucy Alie for the hospital to

purchase the freehold of its premises at Prescot Street. This tactical

change may be ascribed to a hope that their new landlady, who had recently

inherited Leman’s estate, might be more amenable. Yet the scheme led nowhere

and by October the committee had returned to Worrall, who now offered a £40

deduction and asked for his son to be made a life governor of the charity to

compensate for his expenditure on improving the land. In December the hospital

reached an agreement with Worrall to purchase the land for £800, with the

condition that the City would grant the hospital its long-term copyhold.

Negotiations with the City Lands Committee for its 500-year lease from the

Wentworth Estate were no less intricate. As the hospital was not an

incorporated body, the City could not make an agreement with the charity but

was prepared to make a deal with six or more gentlemen acting on its behalf.

The City also indicated that it was only willing to part with the field lying

east of Whitechapel Mount. Richard Coope, George Garrett, Dr James Hibbins,

Boulton Mainwaring and Richard Sclater offered to act on behalf of the

hospital. By July 1750, they had agreed to acquire the City’s interest in the

Mount Field for the remainder of its 500-year lease.

Mainwaring’s design

In May 1751, the hospital’s building committee instructed Mainwaring to

prepare a plan for a building to accommodate 200 patients, with provision for

future enlargement. He presented five plans to the building committee, of

which two were selected for further consideration. No drawings of the five

designs survive but the minute books record that one of the selected plans was

designed to accommodate 198 patients in each wing with a total capacity of

396, whereas the other would accommodate 366 patients.Mainwaring was

instructed to seek advice from the hospital’s physicians and surgeons,

particularly in relation to room height, and to prepare estimates. The

committee decided that the projected expense of both plans was excessive and

that a smaller building ‘might be sufficient for the present’. Mainwaring

was asked to draw up a new plan ‘as near as he could’ to one of the proposals

for a hospital for 300 patients that could be extended as required in the

future, along with estimates for the building with, and without, ornament.

Revised designs for a building for 312 patients were presented to the

committee in September and ‘plan and elevation number six without the

ornaments’ approved.

The chosen design was for a hospital composed of three detached ranges linked

by colonnades. No drawings of this early plan survive, but a description of

its basic form recalls Wren’s unexecuted designs for Greenwich Hospital of

1694–1700 and Gibbs’s plan of around 1730 for the rebuilding of St

Bartholomew’s. Mainwaring might also have borrowed from the Foundling

Hospital, built between 1742 and 1754 to designs by Theodore Jacobsen. The

main hospital buildings there were planned as three detached ranges linked by

short lobbies, enclosing three sides of a courtyard.

Whatever the projected advantages of the chosen plan, by the next month it had

been reconsidered ‘under the several heads of accommodation, convenience,

durableness, and expense’, and declared ‘capable of great improvements’.

Mainwaring, whose efforts had moved to examining the site in preparation for

foundations, prepared a new design for a single building with attached

wings. This was considered superior on each of the four points. Firstly,

it would accommodate 350 patients. Secondly, its arrangement was judged to be

more convenient for patients and staff, with south-facing wards (deemed the

preferable aspect for patients) and protection from weather conditions and

dust from Whitechapel Road. Thirdly, the committee argued that a continuous

building would be ‘in its nature stronger and more lasting, than the same

quantity divided into three’. Finally, the plan for a smaller building was

less costly and saved the expense of colonnades. In another economising

measure, plans for a chapel were omitted as prayers could held in the court

room. It was also decided that the hospital should be positioned parallel to

Whitechapel Road and set back by seventy feet or more for the governors’

coaches. In December, Plan No. 8 was approved by a General Quarterly Court and

Mainwaring appointed as surveyor for the proposed building.

The final plan was publicized by an engraving produced by John Tinney, who was

commissioned to carry out the work with ‘all expedition’. Three hundred copies

were circulated to the governors to generate donations to the building fund,

and also to reassure benefactors that there was ‘nothing ostentatious,

sumptuous or unnecessary intended’ in its design. Mainwaring’s final

design for the new hospital reflects this concern for avoiding extravagance.

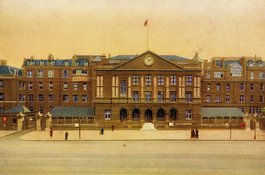

The north front was to have a plain, symmetrical façade of twenty-three bays

with a projecting centre capped with a pediment. With ornament on the exterior

restricted to a Doric entrance porch, a dentil cornice and stone doorcases at

the side entrances, the main elevation was modest yet dignified in character.

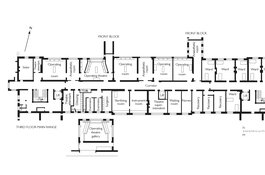

The new building had a U-shaped plan composed of a three-storey central block

with two rear wings, east and west. The main block contained a central

corridor and two large wards positioned on the south side of each floor. The

wards were serviced by lobbies containing sinks, privies, and nurses’ rooms.

On the ground floor, the north side of the central block was occupied by

offices for the apothecary, physicians, nurses and stewards. The first floor

had a large court room that doubled as a chapel at its centre, flanked by

offices for the surgeon, matron and secretary. The rear wings, identical in

plan, contained back-to-back wards separated by spine walls with central

fireplaces; an arrangement similar to the ward blocks at St Bartholomew’s.

Construction

The hospital was constructed to Mainwaring’s plain and practical design

between 1752 and 1778. The central block was built first and completed in 1759

under his supervision. The east wing was built in 1771–4 and the west wing in

1773–8, both under the supervision of Edward Hawkins, who succeeded Mainwaring

as hospital surveyor in 1771.

Central block, 1752–9

After plans for the new building were settled in December 1751, Mainwaring’s

efforts turned to its construction. John Mann, carpenter, and Thomas Andrews,

bricklayer, were contracted to build up to first-floor level. The foundation

stone was laid on 11 June 1752 in a ceremony attended by noble patrons and

dignitaries. Progress was swift, yet it seems that the building committee felt

that it would be too risky to attempt the entire building. When the workmen

completed their contracts in December, Mainwaring was asked to prepare

separate estimates for finishing the central block and its wings. In February

1753, new contracts were advertised for completing only the central block. Yet

before any were agreed, Mainwaring’s report on the cost of finishing the

central block delivered a blow to the building committee. His estimate of

£5,300 was far higher than the sum of cash held in the building fund and

annuities held in the name of trustees, leaving a shortfall of more than

£1,150. Despite the shortage of funds, building works stumbled along. In April

and May, Edward Gray was hired as bricklayer, Joseph Clark as carpenter and

Sanders Oliver as mason. Progress remained steady, suffering only occasional

setbacks. The only serious and recurring obstacle was cash flow. Mainwaring

increased his estimate for the central block to £5,700, and, though it was

covered in by the end of March 1754, work then came to a halt due to a lack of

funds. The suspension of building activity coincided with worsening

conditions at Prescot Street. The hospital’s governors convened to consider

the situation and emphasized the importance of finishing the new building. A

subscription was launched to raise funds and the building committee ‘readily

agreed’ to an offer from several governors to lay one of the floors at their

own expense. Donations trickled into the building fund and work resumed

in 1755, when workmen were employed to finish the new building. Gray and

Oliver continued as bricklayer and mason, and Joel Johnson was appointed as

carpenter and joiner, despite the debacle over shoddy workmanship at Prescot

Street. Building works now progressed steadily without any serious hiccups

and, though they continued until 1759, the hospital moved into its new

building in Autumn 1757. The lease of the infirmary’s houses on Prescot Street

was relinquished immediately.

The allocation of rooms in the completed range did not differ from

Mainwaring’s final design. The cellar storey comprised a long passage

providing access to stores, laundries and wash-houses paved with Purbeck

stone. The south-facing wards of the central block had large stone

chimneypieces and were furnished with plain wooden bedsteads. A handful of

rooms, including the court room, the committee room and offices for the

physician, surgeon and apothecary had wainscoting to a height of five feet. A

surgery, a bleeding room and a cold bath were positioned on the ground floor,

and an operating theatre in the attic. The central block successfully brought

together all of the hospital’s activities under a single roof, with room at

first for 130 patients. The number of beds increased in the following years

and by 1765, there were 190.

East wing and west wing, 1771–8

After the completion of the central block, plans to build the proposed side

wings rested until 1770. The revival of building activity coincided with

improved finances, bolstered by a legacy from Anne Crayle, a spinster

landowner who bequeathed much of her wealth to the capital’s voluntary

hospitals. Despite this significant boon, the newly reinstated building

committee proceeded cautiously. At first Mainwaring was asked to prepare a

plan and an estimate for a single wing, to be constructed on the foundations

already laid. His plan for the east wing conformed to the original design for

identical three-storey wings of six bays, with paired wards on each floor and

a basement. In 1771, Thomas Langley was appointed as carpenter, Thomas Barnes

as bricklayer, and Isaac Ashton as mason. As work on the east wing commenced,

Mainwaring warned that he was struggling to perform his duties, particularly

‘the constant attendance upon the workmen requisite’, due to the distance from

his home. He recommended that Edward Hawkins, a local developer on the Leman

Estate in Goodman’s Fields, should act as surveyor in his absence, yet

promised to attend as frequently as possible. However, poor health

intervened and at the end of the year, at the age of sixty-nine, Mainwaring

resigned.

Under Hawkins the building works progressed steadily. Contracts were agreed to

finish the east wing in 1772 and by the following spring, its completion was

in sight as advertisements were circulated for a contractor to furnish it with

ninety beds. At this point, there was enough optimism for the hospital to

assemble a building committee to manage the construction of the west wing;

that took place in 1774–8 and included many of the same workmen.This ambitious

strategy soon faltered under financial pressure. An appeal for donations in

1774 revealed that the completion of the east wing and shell of the west wing

had depleted the building fund, leaving a shortfall of cash to pay the workmen

and a deficiency of almost £900 to finish the building. Despite these

financial straits, work trundled forward. A plea for support was successful by

the following year, when the building committee reported that its fund

contained over £1,000 for finishing the west wing. This news prompted a flurry

of activity and by December 1777, the west wing was largely finished.

The completion of the west wing in 1778 signified the realisation of

Mainwaring’s design for the hospital’s first purpose-built home. At this point

in its history, the hospital overlooked Whitechapel Road from its position

east of the Mount and was bounded by open fields to the south. By the mid

1780s, a narrow range had been added at the west end of the hospital to

provide coach houses and a mortuary. Improvements were also made to the

hospital’s immediate surroundings: a patients’ garden was nestled between the

ward wings and a kitchen garden cultivated from waste ground at the west. The

charity, by now known as the London Hospital, released pamphlets which boasted

of its convenient location close to the shipping activities of the port and

Spitalfields, a nucleus for manufacturing, as well as the health benefits of

its ‘airy situation’. With eighteen wards fitted up with about 215 beds, the

new building offered a permanent base from which the charity could intensify

its work. By 1786, the charity had treated nearly 450,000 patients since its

modest beginnings, cementing its status as an institution of critical value to

impoverished working families in the east of London.

West wing and east wing extensions, 1830–42

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

Plans for the first substantial enlargement to the hospital arose in 1830 in

response to rising patient numbers, a by-product of rapid population growth.

The establishment of the enclosed docks and the expansion of local

manufacturing demanded an army of labourers. Many ended up residing in densely

populated slums prone to the spread of disease, and were exposed to ‘fearful

and appalling accidents’ at work. A newly assembled building committee

observed that within a year, the hospital had been forced to refuse admission

to more than 870 cases. A wing extension promised to provide ninety additional

beds and separate wards to isolate contagious patients. These motivations

coincided with low construction costs and a significant legacy from Edward

Hollond, a governor with property in Cavendish Square and Suffolk. The

committee anticipated that an extension to one of the rear wings would cost

£8,000, which would be covered securely by Hollond’s bequest, existing funds

and a fundraising campaign.

Alfred Richardson Mason, hospital surveyor since 1821, was asked to prepare

plans for a wing extension. His father, William Mason, was a local bricklayer

and governor who had applied unsuccessfully for the post of surveyor during

its last vacancy in 1806 and served on the hospital’s building committee. The

chosen plan was reviewed by the medical staff and many of their

recommendations adopted. Mason proposed extensions to the east and west wings

to provide new wards. The external appearance of the extensions matched the

austerity of Mainwaring’s design. On each side a three-bay projection, capped

with a pediment, connected the existing wing to a new ward wing composed of

six more bays. On the ground, first and second floors, Mason’s plan followed

the arrangement of paired wards separated by a spine wall with a central

fireplace. The new wards were connected to the earlier wards by lobbies, each

containing a washing room and a bath room, along with a kitchen and a nurses’

room. In the basement of the west wing, the extension was allocated to the

hospital’s medical officers: a long patients’ waiting hall was bordered by a

dispensary and separate physicians’ consulting rooms. Staircases in the

second-floor lobbies rose to an attic storey with rooms for special cases,

including separate rooms for private patients in the east wing and a ward for

contagious cases in the west wing. The hospital was surrounded by an

assortment of open spaces, including a drying ground adjacent to the laundry

and a burial ground to the south of the quadrangle.

William Colebatch was employed as contractor for the west wing extension in

June 1830, and construction began without delay. The new wards opened in

August 1831 and were fitted up with fifty iron bedsteads, an improvement from

the earlier wooden beds judged to be ‘receptacles for and filled with

vermin’. Although the number of beds was considerably less than the

ninety initially intended, the extension proved to be of immediate value as it

opened before the first outbreak of a cholera epidemic. Sir William Blizard,

eminent surgeon to the hospital, circulated a plea to the House Committee for

special procedures to combat its spread, including the provision of an

isolated place to receive sufferers. Although the hospital declined to admit

cases of cholera, on the grounds that it was an untreatable disease, the new

attic ward was used to isolate infected inpatients.

A lack of funds delayed the construction of the east wing extension, as the

hospital struggled with financial pressure caused by rising patient numbers.

An appeal for donations launched during the charity’s centenary year was a

success. Robert and George Webb were contracted as builders in December 1840.

The extension was finished in 1842 and Mason paid a fee equal to five per cent

of the building costs; by now the position was no longer honorary and this was

termed the ‘usual’ surveyor’s commission. The only significant departure

from Mason’s earlier plan wasthe provision of separate wards for Jewish

patients, which arose from a request delivered in 1837 by a committee of

Jewish gentlemen devoted to ‘the more effectual relief of the sick poor of the

Jewish community requiring medical aid in and about London’. This deputation

on behalf of ‘Gentlemen of the Hebrew Nation’, noted for their generosity and

support towards the hospital since its inception, was made by Joel Emanuel and

Abraham Levy. In addition to exclusive wards for Jewish patients, the

committee requested a team of Jewish medical staff and a separate kitchen to

prepare kosher food. By these measures, it was hoped that Jewish patients

would ‘receive that consolation and peace of mind which would prove most

consonant with their religious feelings’. Although the committee offered

some financial support and predicted the initiative would encourage donations,

the project was deferred until funds were secured for the hospital’s

enlargement. The centenary festival attracted donations and, when the east

wing extension was completed, two wards in the earlier part of the hospital

were set aside for men and women.

The effects of this improvement were not permanent due to demand for beds. By

1854 the House Committee had decided to allocate portions of wards to Jewish

patients as an interim solution until a future enlargement of the hospital.

Despite this failure, the wing extensions were considered an overall success.

Their completion was followed by a sharp decline in mortality rates inside the

hospital from ten per cent to eight per cent, and then as low as six per cent.

Further alterations to the east and west wings followed in 1853–4, with the

addition of fireproof staircases and water closets at the south ends to

designs by Mason. This extension was carried out by George Myers, along with

the formation of staff dormitories in the attics of the north end of each

wing.

Alexandra Wing, 1864–6

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

Over time, the hospital was increasingly inundated with patients arriving from

the local area and remoter parishes such as West Ham. Since the completion of

the wing extensions of 1830–42, the volume of patients had more than doubled.

By the 1860s, more than 30,000 people were treated as inpatients and

outpatients each year. Overcrowding was not confined to the wards, as medical

officers and nurses endured cramped conditions with little promise of rest.

Due to prolonged shifts and a lack of dormitories, nurses were frequently seen

to be ‘overcome with sleep’ and the matron insisted that her staff could not

be increased without additional sleeping accommodation. By 1862 the situation

had become untenable and a report on overcrowding pronounced ‘a very serious

defect in the arrangements of the London Hospital’.

The hospital turned to its surveyor, Charles Barry Jr, to prepare plans for an

extension to the outpatients’ department. Acting as hospital surveyor from

1858, Barry approached his responsibilities in an efficient manner from

offices in Sackville Street, proposing to attend committee meetings for an

extra charge in addition to a nominal salary and commission rate. Barry

designed a long single-storey building that would run parallel to the existing

surgical and physicians’ outpatients’ departments housed in the west wing. Yet

plans for this extension were stalled as the House Committee contemplated a

solution for the longer term. The matter was delegated to a building

committee, which promoted substantial alterations and argued that ‘the entire

system is one of undue pressure, subversive of sanitary arrangements,

inconvenient to the professional staff, (and) unfair towards the patients and

the servants of the hospital’.

The proposed solution was to build a three-storey wing with a basement and an

attic, extending west parallel to Whitechapel Road. Barry’s plan promised room

for about seventy beds, with separate wards allocated for children, obstetric

cases, and Jewish patients. The hospital had received a series of requests for

the reinstatement of separate Jewish wards since their closure, but was

limited by the pressure on hospital spaces. The wing extension enabled the

hospital to arrange Jewish patients in separate wards on one floor, near to a

kosher kitchen. The new wing was divided roughly into two parts. A three-

storey maisonette with bedrooms and servants’ quarters was carved from the

west end of the wing for the house governor, a resident officer who managed

the daily workings of the hospital and its expenditure. Each floor of the east

side of the building comprised a central corridor flanked by wards or offices.

The basement secured a new surgical outpatients’ department, with an extensive

waiting hall to make the customary ‘lengthened detention’ less onerous, and a

consulting room flanked by rooms for dressing injuries. An attic dormitory for

night nurses addressed fears that a lack of supervision compromised their

efficiency and ‘quality’. The intermediate floors were given over to wards,

with the exception of a new committee room and secretary’s office positioned

on the ground floor.

The exterior of the west wing reflected its disjointed plan. On the north

elevation facing Whitechapel Road, a projecting bay capped with a pediment

marked the junction between the wards and the house governor’s residence. The

west elevation had a raised entrance porch to the house governor’s maisonette,

which overlooked a private walled garden at the south. A significant

innovation in the new wing was the construction of a narrow tower to contain

sanitary facilities, specifically a water tank at its peak and water closets

below. At Barry’s insistence, the building was constructed with fireproof

concrete floors and staircases. The House Committee initially hesitated over

the additional expense, yet was persuaded by the surveyor’s warnings that the

hospital could be criticized for failing to introduce fireproof floors, which

also possessed soundproof and ‘verminproof’ qualities.

The new wing was constructed in 1864–6 by Hill & Keddell, contractors

based in Whitechapel Road. It was financed partly by charitable donations,

including substantial gifts from local businesses and the brewer Sir Thomas

Fowell Buxton, chairman of the House Committee. Many of the hospital’s staff

and supporters were recognized in the naming of the wards: one was named

‘Buxton’, and ‘Davis’ commemorated the present and former vice-presidents. A

ward was named ‘Blizard’ in memory of the hospital’s eminent surgeon. The

foundation stone was laid in July 1864 in a ceremony that saw Whitechapel

awash with crowds and decorated with bunting. The building was bestowed with

the first name of the new bride of the Prince of Wales, an association

intended to inspire ‘respectful admiration’. Its opening was not

accompanied by such celebration; formal inauguration had to be abandoned due

to another outbreak of cholera. In July 1866, patients were moved into the new

wing to provide space for cholera patients.

The completion of the Alexandra Wing allowed various improvements to be

effected elsewhere in the hospital, as rooms were modified and reassigned.

These alterations were also carried out by Hill & Keddell and continued

until 1868. In the basement, an ophthalmic ward was set up and the medical

outpatients’ department extended into rooms formerly occupied by its surgical

counterpart. On the ground floor, the entrance vestibule was extended and a

large receiving room added at its west. Bedrooms, sitting rooms and offices

were provided to improve conditions for the medical officers and their

pupils.

Rowland Plumbe and Joseph George Oatley oversaw various alterations to the

Alexandra Wing in the twentieth century, including the formation of a

coroner’s court in the basement and a single-storey extension at the west. An

endowment by James Hora, a vice-president of the hospital, led to the opening

of the Marie Celeste maternity department in 1905. Due to persistent pressure

on vacant space for hospital expansion, the house governor’s private garden

was not destined to survive. By 1960 it had been converted into an ambulance

station, with a covered parking bay and ramped entrance into the hospital.

This in turn was short-lived, as the Alexandra Wing and the adjoining

ambulance station were cleared for redevelopment in 1974.

Grocers’ Company’s Wing and further expansion, 1873–6

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

The hospital expanded eastwards in 1873–6 with the construction of the

Grocers’ Company’s Wing, a post mortem department and a nurses’ home. Their

completion secured the London Hospital’s status as one the largest general

hospitals in the country, with almost 800 beds. The only surviving remnant of

this building programme is the north range of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing,

which presents an orderly 120ft frontage to Whitechapel Road terminating at

its junction with East Mount Street. Two bays of the south part of the wing

survive in 2019; the rest was cleared in the 1960s for the construction of the

Holland Wing.

This significant enlargement was catalysed by rising numbers of inpatients.

Despite the completion of the Alexandra Wing in 1866, the hospital struggled

to keep pace with the demand for beds. In 1870 the house governor, William

Nixon, recorded an ‘extreme pressure of inpatients’, exceeding 500 at any one

time. Parts of the old medical college were converted into quarantine

wards for contagious cases and wards for patients afflicted with erysipelas, a

bacterial skin infection, opened in a single-storey building in East Mount

Street. The provision of isolation wards evidently failed to secure a long-

term solution to overcrowding. A few years later, Nixon reported an alarming

‘state of repletion’ in the wards. He declared that the hospital was ‘not

large enough’ to fulfil the demands of the surrounding district, despite its

strict policy of admitting only urgent and curable cases. This deficiency

was exacerbated by the practice of providing separate accommodation for more

than twenty-one types of inpatients, for the most part divided by gender,

treatment, and medical condition. This classification system led to frequent

shortages in beds for particular cases, which made it necessary to mix

different types of patients in the wards. Additional room was most urgently

required for medical cases, children and obstetric patients.

The proposed solution was to extend the hospital to provide 200 additional

beds, increasing the number of inpatients by a third. A public fundraising

campaign was launched with the aim of securing £100,000 towards the

construction and operating costs of an enlarged hospital. A new wing extending

east from the central block was deemed preferable to ensure the proximity of

wards to the ‘working centres’ of the hospital, namely the lifts, the staff

offices, the laundry, the kitchen, the operating theatre, and the

depository. The intended site was occupied by the old medical college and

a carriage shed fronting Whitechapel Road, along with various workshops, sheds

and stables in East Mount Street. The building programme was overseen by

Charles Barry Jr, who had assumed the position of consulting architect to the

hospital in 1870. The House Committee had reorganized Barry’s responsibilities

amid concerns that he was ‘too much engaged in other directions to give

sufficient personal attention to his duties’. He was invited to adopt an

advisory role and to delegate supervision of repairs to a salaried surveyor.

This task was assigned to J. A. Thornhill, the clerk of works during the

construction of the Alexandra Wing.

The centrepiece of this wave of hospital expansion was the Grocers’ Company’s

Wing, named in recognition of a donation from the City livery company. Their

gift was accompanied by various conditions, including that the wing should be

completed within three years. While the House Committee had intended to

postpone building work until the fundraising campaign had realized its target,

the Company stipulated that construction should begin immediately. As the

projected expense of the wing exceeded £25,000, it was reasoned that sole

responsibility for its design should be entrusted to Barry. He planned a

three-storey wing with a basement and attics, with an L-shaped plan composed

of two blocks; a north range extending east from the front block in line with

Whitechapel Road, and a south range running along East Mount Street. This

arrangement preserved a yard between the extension and the main building, with

the benefit of supplying light and ventilation to the inward-facing wards. The

principal floors followed the pattern of the earlier ward wings in plan,

comprising paired back-to-back wards separated by a central spine wall with

fireplaces. Partitions at the west end of the wards formed linen stores and

areas for water closets, kitchens and sinks. The attics provided dormitories

for seventy nurses.

The foundation stone was laid on 27 June 1874. Construction by Perry & Co.

was complicated by the intended route of the East London Railway, set to curve

beneath the north-east corner of the wing. As a precautionary measure, the

foundations nearest the railway line were excavated to a depth of thirty-five

feet and filled with concrete. The outward appearance of the wing matched the

austerity of the Alexandra Wing, with plain brick elevations decorated by a

string course and a dentil cornice of Portland stone. Its tiled roof was

punctuated by pedimented dormer windows and tall brick chimneys with

oversailing tops. Two rear sanitary towers rose above the roofline of the wing

with louvred openings and steeply pitched roofs; one contained a water tank

and the other was fitted with a ventilation shaft. There were fireproof

floors. At street level, a wooden carriage shed built in 1876 occupied the

narrow stretch between the north front and Whitechapel Road.

The Grocers’ Company’s Wing was formally opened by Queen Victoria in March

1876, in a celebration reported to have lent ‘an attractive and joyous aspect

to (an) ordinarily dull and dingy but busy quarter’. In the following

months, patients were moved gradually into the new wards, which were praised

for their ‘light and pleasant aspect’. The wards were fitted with

specialized ventilation systems devised by Thomas Elsley and George Jennings.

Two rows of evenly spaced beds extended across the long walls of each ward.

This utilitarian arrangement was relieved by potted flowers and pictures on

the walls, and formal plaques bearing the name of each ward. At the time of

writing (2019), the appearance and plan of the north range of the Grocers’

Company’s Wing had survived with only minor alterations, despite adaptation

and changes in room use.

The scale and siting of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing precipitated improvements

elsewhere in the hospital. The new wing was preceded by the reconstruction of

the post mortem and pathological departments in 1873–4. These departments were

formerly housed in the old medical college, and set to be displaced by its

demolition (see below). Their new base was a single-storey building in East

Mount Street. As no drawings survive, little is known about the form of the

post mortem department aside from its provision of a pathological room and a

post mortem theatre. The building was constructed by Perry & Co. to

Barry’s design. Plans for the new wing also gave rise to a scheme for the

hospital’s first purpose-built nurses’ home.

Remodelling and enlargement, 1890 to 1905

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

Between 1890 and 1906, every part of the hospital was extended, rebuilt or

remodelled under the supervision of the architect Rowland Plumbe. This

ambitious building programme upgraded the hospital in line with shifting

ideas, innovations and specialization in healthcare. The use of anaesthetics

from the 1840s had extended surgical practice, contributing to an increase in

the number of operations carried out in general hospitals. This pattern was

reflected at the London Hospital, where 420 operations were performed in 1881,

1,114 in 1891, and 2,711 in 1901. New operating suites were designed with

separate anaesthetic rooms to relieve patients from entering theatre in a

conscious state. Ventilation was an established planning concern in hospitals

due to the miasma theory, which held that disease is spread by noxious air.

From the late 1850s, hospital planning was influenced by Florence

Nightingale’s recommendation of cross-ventilated pavilion wards and sanitary

towers separated by airy lobbies. Although miasma theory was outmoded from the

1880s by the acceptance of germ theory, the modern principle that disease is

spread by bacteria, the tenets of pavilion planning continued to be widely

adopted. An increasing focus on eliminating germs led to the redecoration of

hospital spaces with smooth, impermeable and easily cleaned surfaces. Like

other institutions of its kind, the hospital installed new manufactured and

sanitary finishes such as terrazzo flooring, Opalite wall tiles, and linoleum.

The discovery of Röntgen rays and the invention of the Finsen lamp in the

1890s led to the formation of specialized departments for radiography and

light treatment. Alterations to the main hospital building were carried out in

parallel with the construction of purpose-built blocks to accommodate

specialized departments, including an outpatients’ department, an isolation

block and a laundry. This ambitious building programme relied on the

resourcefulness of the hospital’s chairman, Sydney Holland, the second

Viscount Knutsford, to attract donations. Holland was elected to the

chairmanship in 1896, and in the following year the Prince of Wales Hospital

Fund (later known as the King’s Fund) offered an annual subscription of £5,000

on condition that the hospital would spend £100,000 of its own capital on

making its buildings ‘up-to-date and efficient’.

Rowland Plumbe

In 1883 the House Committee decided to abolish the position of consulting

architect and seek advice from ‘various persons from time to time instead of

keeping to their own officer’. In the following year Plumbe was requested

to draw up plans for a large extension to Old Home, the nurses’ home adjoining

the east wing (XREF). Plumbe was an experienced architect with local origins.

He was born in 1838 in Goodman’s Fields, where his parents managed a business

selling arrowroot for medicinal use. The Plumbe family had links with the

Wycliffe Chapel in Philpot Street; his father served as a deacon at the chapel

and was a friend of its minister, Dr Andrew Reed. Plumbe studied architecture

under T. L. Donaldson at University College London and was articled to N. J.

Cottingham and Frederick Peck, followed by an interlude with F. C. Withers in

America. After returning to London in 1860, Plumbe started working as an

architect from Tokenhouse Yardin the City, establishing an extensive and

varied practice. Plumbe developed an interest in medical buildings, taking on

commissions at Poplar Hospital, St Mark’s Hospital and the National

Orthopaedic Hospital. Despite its fruitfulness and longevity, Plumbe’s

association with the London Hospital was not formalized till 1906 by his

appointment as consulting architect and election to serve on the House

Committee. Plumbe’s involvement in the hospital’s affairs continued till his

death in 1919 at the age of eighty-one. A bronzed terracotta bust by Sir

George Frampton, a gift from one of Plumbe’s daughters, was subsequently

placed in the surveyor’s office of the works department.

Front Block, 1890–1

The front block, built in 1890–1 by Perry & Co., was intended to improve

the practicality of the central block, yet also to bestow the hospital with a

dignified public entrance. A five-bay arcade provided a porte cochère for

horse-drawn ambulances, with sloped side approaches and a central stepped

entrance for pedestrians. The principal storey was occupied by a chapel,

expressed externally by round-arched traceried windows. The composition was

crowned by a pediment with a clock, and flanked by a pair of pavilion towers

with pyramidal roofs and finials. The front block was designed to remedy

a number of deficiencies in the central block, including the obstruction of

the main corridors by the double-height chapel and the impracticality of a

stepped entrance for emergency cases. The operating theatre and space for

clinical teaching were also outdated due to the rising number of operations

and the implementation of anaesthetics and sterile surgical techniques.

The porte cochère opened into a vestibule with a porter’s box and an office

for medical students. A hallway beyond provided access to a waiting room,

examining rooms and a receiving room. The upper floors were separated from the

central block by a light well. The first floor of the front block contained a

new chapel, furnished with a pulpit, seats and chancel furniture from its

predecessor. A five-light stained-glass memorial windowby Arthur J. Dix,

depicting ‘Christ Healing the Sick’, was donated by Emily Mary Coope in memory

of her husband Octavius Edward Coope, the local benefactor and brewer.

Dormitories for nurses and servants were in the attic storey. The transferral

of the chapel to the front block enabled the reconfiguration of the upper

floors of the central block, including the provision of a clinical lecture

theatre and an operating theatre on the second floor.

These building works were undertaken in collaboration with Dr Louis Parkes, a

leading sanitary expert engaged as assistant professor of hygiene at

University College London. The hospital’s matron Eva Lückes had raised

concerns about conditions in 1889, after observing illness among the nursing

staff. The matron’s observations were reinforced by reports of blood poisoning

and infected wounds among patients. Parkes was appointed to consider ‘every

sanitary detail connected with the hospital’, and submitted an exhaustive

report in 1890. The hospital resolved to carry out the most critical

recommendations, including the removal of old brick sewers and the

construction of a new drainage system formed of salt-glazed pipes with

manholes and traps. Parkes stressed the importance of building sanitary towers

to the east wing, the west wing and the Alexandra Wing, each containing baths,

water closets and sink rooms. He also recommended the replacement of ceiling

ventilators with Tobin’s tubes in the old wards, the installation of sash and

hopper windows, and redecoration with impermeable surfaces such as glazed

tiles and linoleum. After examining the improvements in 1893, Parkes concluded

that the work had been ‘exceedingly well done’. Between 1888 and 1894 the

hospital invested approximately £38,000 on building works, including £18,560

on the front block. The addition of sanitary towers cost £7,616, while £8,000

was spent on other improvements. Outbuildings at the east end of the hospital

were reconstructed by Perry & Co. to provide a Jewish mortuary (or Bet

Taharah),a new carpenters’ workshop, a destructor and a disinfector.

Remodelling and extension of the main hospital building, 1899–1905

The front block extension and sanitary improvements were the first components

of an extensive building programme overseen by Plumbe. The works intensified

between 1899 and 1905, when each portion of the hospital was remodelled and

extended. The scale and scope of the works were determined by 1901, when the

House Committee announced plans to enlarge and reconfigure the hospital and

construct a number of purpose-built blocks in its vicinity, including an

outpatients’ department, a post mortem department, an isolation block, and a

laundry. The estimated cost of £370,000 was described as ‘huge but absolutely

necessary expenditure’, yet it was calculated that the final cost reached

nearly £410,000.

Not a single patient bed was closed during the building works, owing to the

construction of temporary buildings in the hospital’s gardens. A single-storey

iron building containing wards for ninety-eight patients and space for the

photographic and X-ray departments was constructed in 1898–9 by the Bermondsey

builder William Harbrow, who claimed a specialism in iron buildings. This shed

also contained the hospital’s first Finsen lamp, a pioneering light radiation

machine designed to treat lupus vulgaris, a tuberculous skin infection. The

lamp was named for its Danish inventor and Nobel laureate Niels Ryberg Finsen,

and donated by Queen Alexandra in 1900. Another temporary building was

assembled on the house governor’s garden in 1899–90 to provide space for the

outpatients’ department. This shed was constructed by Humphreys of

Knightsbridge, a leading supplier of prefabricated iron hospitals. Both

buildings were demolished in 1905.

Central block and front block

Significant alterations were undertaken in the central block and the front

block by Perry & Co. between 1900 and 1903, after the acceptance of a

tender of £61,380. Building works proceeded immediately, commencing with the

underpinning and strengthening of the walls in preparation for two new

storeys. Spacious top-lit well staircases were inserted at the east and west

ends of the wing, connected on each floor by the existing corridors. Each

staircase lobby contained separate lifts for passengers and dead bodies, along

with sink rooms and water closets. In the basement, the kitchens and the

porter’s offices were replaced by dormitories for the housekeeping staff and

laundry maids. A boiler room was installed for supplying hot water and

sterilized air to the operating theatres. The ground-floor receiving room was

extended and remodelled, and most of the chapel was converted into staff

dormitories and a clinical theatre. A redecoration scheme included the

application of mosaic floors by Diespeker & Co. over the main lobby and

the receiving room, and linoleum in the main corridor.

The third-floor extension secured an extensive operating department containing

a large theatre for teaching demonstrations, four operation rooms, and

adjoining anaesthetic rooms. Only one operating theatre and three operation

rooms were intended initially, but a modification to the building contract

secured an extra suite. The department was arranged along the north side of

the central block, with large windows forming a rambling sequence of glazing

that has not been altered substantially. A top-lit corridor divided the

operating suites from a series of south-facing offices, including examination

rooms, waiting rooms, surgeon’s offices, and rooms for instruments and

sterilization. Recovery rooms were conveniently flanked by rooms for sisters

and nurses, who were also allocated bedrooms on the fourth floor. The £13,000

cost of the operating department was donated anonymously by Benjamin (or Benn)

Wolfe Levy, a businessman and philanthropist, on condition that the theatres

were ‘open to every poor patient irrespective of creed or nationality’. Levy’s

generosity was commemorated by a plaque erected after his death in 1908. A

flat roof was fitted with water tanks with a capacity of 10,000 gallons,

approximately a day’s supply for the hospital.

East wing and west wing

Plans for the remodelling and extension of the east wing were approved in

1901. The work was carried out by Perry & Co. in collaboration with W. G.

Cannon & Sons as hot water engineers and James Slater & Co. as

ventilating engineers. Works commenced with the underpinning and strengthening

of the spine walls with stanchions for the construction of two new storeys.

The basement laundry was transferred to a purpose-built detached block, and

its former rooms converted into porters’ accommodation. A number of

alterations were effected to improve ventilation in the wards, including the

enlargement of windows and the raising of ceilings on the second floor. The

insertion of openings between the back-to-back wards provided a degree of

natural cross-ventilation. The attics were rebuilt to provide a new ward on

the third floor. The fourth-floor extension provided a new kitchen with a

scullery, pantries, offices, and an external goods lift. The south end of the

floor provided bedrooms for nurses and sisters, adjacent to Old Home.

The west wing was also extended by two storeys and its existing wards

remodelled. Plumbe’s plans were submitted in June 1901 and Perry & Co.

instructed to start work immediately. Yet the impracticality of builders

taking over the west wing, which housed the medical outpatients’ department,

swiftly became apparent. The building work was postponed till the completion

of the new outpatients’ department, and carried out in 1903–4. The basement

rooms formerly occupied by the medical outpatients’ department were converted

into a series of isolation and padded rooms for psychiatric cases and patients

requiring constant supervision. The rest of the basement was devoted to an

ophthalmic department containing specialist wards, an operating theatre, and a

refraction room for eye examinations. The wards on the upper floors were

remodelled to improve ventilation and the comfort of patients. The first- and

second-floor wards had access to external balconies, reflecting a growing

interest among medical practitioners in the beneficial effects of fresh air

and sunlight.

The fourth-floor extension was devoted to Jewish patients, with two wards

divided by a central lobby containing a kosher kitchen and a scullery. One for

men and one for women, these wards were named ‘Rothschild’ and ‘Goldsmid’

respectively. The reinstatement of dedicated Jewish wards reflected the

reality on the ground that the London Hospital was the principal hospital used

by the now significantly larger Jewish community. These wards were formally

opened in November 1902 by the prominent banker and philanthropist Leopold de

Rothschild, in his capacity as vice-president of the hospital. Other Jewish

philanthropists such as Sir Samuel Montagu and Sir Benjamin L. Cohen served on

the House Committee, organized appeals, and made personal donations to the

hospital.

Alexandra Wing and Grocers’ Company’s Wing

The external appearance of the Alexandra Wing was not much altered during the

building programme, yet its interior spaces were remodelled extensively. The

alterations were completed in 1905 by Perry & Co., with Cannon & Sons

as hot water engineers, Slater & Co. as ventilating engineers, and the

plumber R. A. Marshall. The removal of the surgical outpatients’ department

from the basement provided space for a coroner’s court with a public gallery,

a witness room and a coroner’s office. The basement also contained a massage

department and offices for the hospital’s surveyor. The ground floor was

converted entirely to administrative use, with a new committee room,

secretarial offices and an estate office. The rest of the wing was devoted to

maternity cases, with a first-floor obstetric operating theatre and a south-

facing ward with a balcony. The Marie Celeste maternity department was

formally opened on the second floor in 1905. Named in memory of the wife of

James Hora, a vice-president of the hospital, the suite contained a labour

room, an isolation room and a lecture room. Three small wards extended along

the south side of the second floor, opening onto a balcony with views over the

rear garden. The attic dormitories were assigned to the maternity staff and

pupil midwives. The Grocers’ Company’s Wing was altered on a

comparatively modest scale. South-facing ward balconies were installed and

windows were enlarged and fitted with patented ‘Luxfer’ prism glass to

maximize light. The basement was reconfigured to form a large surgical ward

for male patients, and the ground floor contained a female surgical ward

equipped with an operating suite. These alterations were completed in

1905.

Gardens and forecourt

Plans were produced for redesigning the gardens in 1906, after the building

works created a state of disarray. The rear quadrangle was bestowed with a

bronze statue of Queen Alexandra created in 1907–8 by George Edward Wade, a

favoured sculptor among the royal family. The statue commemorated her

longstanding support of the hospital and consent to serve as its president, a

title she retained from 1904 to her death in 1925. Alexandra agreed to pose

for the sculpture, which depicts her standing with dignified composure,

holding a sceptre in her right hand. She is garbed in coronation robes, her

state crown, jewels and a pearl necklace. The robust stone plinth has an

inscribed bronze plaque and a bronze bas-relief panel depicting a royal visit

to the Finsen light department in the outpatients’ department. At the centre

of the composition, Alexandra bends to observe a patient receiving treatment

with the use of a Finsen lamp. She is accompanied by King Edward VII and an

entourage of representatives of the hospital, including its chairman Sydney

Holland, the surgeon Sir Frederick Treves, and the matron Eva Lückes. Wade’s

statue is currently positioned on the south side of Stepney Way, in an

incongruous spot beneath the canopy of the new hospital.

In its original position on a raised plinth at the centre of the quadrangle,

the statue was encircled by an asphalt path with straight offshoots leading to

the central block, the east wing and the west wing. A pair of timber shelters

for patients was positioned at the south end of the quadrangle, screening it

from the open ground on the north side of Stepney Way. A porter’s lodge was

also built at the south-east corner of the garden. Perry & Co. were

contracted to construct the lodge and the shelters, along with the weighty

stone pedestal of the statue. The narrow wedge-shaped courtyard to the east of

the hospital, known colloquially as ‘Bedstead Square’ for its proximity to the

steward’s stores, was decorated with planters gifted by the local brewing firm

Mann, Crossman & Paulin. Timber shelters were also built on the forecourt

of the hospital to accommodate patients’ relatives and friends, these

constructed in 1912 by Perry & Co. to designs by J. G. Oatley.

Additions and alterations in the twentieth century

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

The rebuilding and expansion of the hospital under Plumbe’s supervision

created a large medical complex that functioned on modern and efficient lines,

requiring few alterations for some time. The important work of the hospital

during the First World War has been chronicled in the second volume of A. E.

Clark-Kennedy’s institutional history. After emerging from the war in

significant debt owing partly to higher wages and the rising cost of medical

treatment, the hospital opted to introduce a fee of 10s. per week for

inpatients who could afford it. This shift from the institution’s policy of

providing treatment without any charge to its patients was bolstered by the

Insurance Act of 1911, which protected workers from a loss of earnings during

illness. The hospital was associated with discussions over the organization of

healthcare through its physician Lord Dawson of Penn, whose 1920 report

foreshadowed the establishment of the NHS. Despite the introduction of patient

fees, the hospital’s finances were so troubled that 200 beds were closed

temporarily in 1921. Approximately half of these beds were reopened after a

fundraising appeal in 1923, but the rest were sacrificed to provide space for

specialist equipment, offices and staff accommodation, leaving a total of

approximately 850 beds in the hospital.

Interwar alterations

The interwar period witnessed few substantial alterations to the main hospital

building, owing to financial struggles and the longevity of the improvements

made by Plumbe. The works department was headed by J. G. Oatley, who continued

as hospital surveyor till his retirement in 1933. He was succeeded by his son,

Norman Herbert Oatley, who served until the 1950s. Most alterations were

precipitated by the installation of specialized departments, which multiplied

in general hospitals after the First World War. By 1926, the hospital

contained eighteen operating theatres and fourteen specialized departments.

The central block and the front block were the focus for alterations in the

main hospital building, but a number of departments were established in

purpose-built detached blocks in the immediate vicinity. The clinical theatre

adjacent to the chapel in the front block was transferred to the Bearsted

Clinical Theatre to provide space for laboratories, and all but one of the

traceried windows were replaced with a series of workmanlike apertures. A

gynaecological operating suite was installed on the third floor of the central

block, with a bay window that survives on the north front. This facility was

funded by a donation from Louis F. Stanton Bader, a coal dealer of Boston,

USA, in gratitude for the treatment of his wife by the obstetric surgeons

Russell Andrews and Eardley Holland. In 1929, a radium laboratory was

installed on the second floor of the front block.

A covered way was constructed in the quadrangle by William Wood & Sons of

Taplow in 1929–30. The pergola extended from the rear entrance of the central

block along the east side of the garden, providing shelter for patients and

staff. It was financed by Sir William Paulin, the honorary treasurer of the

hospital. A memorial tablet designed by Edwin Lutyens was unveiled in the

front hall in 1933 to commemorate Sydney Holland, the hospital’s chairman.

Isolation wards were installed in the Grocers’ Company’s Wing by Walter

Gladding & Co. in 1935, facilitating the conversion of the Fielden

Isolation Block to wards for private patients.

Post-war rebuilding schemes and extensions

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

In 1940 a bicentenary campaign was launched for a programme of repair and

reconstruction. The earlier building works overseen by Plumbe were commended

for their solid construction and spacious planning, which obviated the need

for large-scale redevelopment. The hospital required new departments to pursue

advances in medicine, such as dietetics, blood analysis and psychology.

Research was restricted by a lack of space and the dispersal of laboratories

around the hospital. William Goschen, the hospital’s chairman, urged that it

would be ‘impossible to keep pace with modern developments without an

extensive scheme of reconstruction’. In the first phase of the proposed

scheme, the clearance of attic nurses’ dormitories was intended to provide

room for clinical laboratories and new aural wards. Later phases promised to

secure improved facilities for the radiology department, a new wing for a

casualty department and fracture clinic, wards for infected surgical cases,

and a new genito-urinary clinic, dental department and light treatment clinic.

The hospital also intended to modernize the operating theatres and the general

wards.

The bicentenary programme was abandoned due to the onset of the Second World

War, which plunged the hospital into preparations for air raids and

casualties. In 1940, the Alexandra Home, the Eva Lückes Home and the medical

college were hit by bombs. The hospital evaded severe destruction until August

1944, when the east wing was damaged severely by a V-1 flying bomb. The

hospital also emerged from the war in significant debt, with meagre hope of

repairing bomb damage and carrying out improvements without assistance from

the state. The establishment of the NHS in 1948 brought the hospital under the

administration of a board of governors that reported to the Ministry of

Health. All patient fees were eliminated and salaries introduced for the

medical staff, who had previously devoted their time to the hospital as

honorary consultants while maintaining private practices elsewhere.

Two ambitious rebuilding schemes were mooted after the Second World War. The

first proposal by Adams, Holden & Pearson, drawn up in 1947, was not

implemented due to limited funds, and the second scheme by T. P. Bennett &

Son was drastically curtailed in the 1970s by the listing of historic

buildings. The unexecuted scheme of 1947 proposed to extend the hospital’s

footprint southwards to Varden Street, producing an extensive and functional

teaching hospital with 1,000 beds. The main hospital building was to be

remodelled to contain administrative offices, laboratories, and wards in the

Alexandra Wing and the Grocers’ Company’s Wing. The southern portion of the

hospital complex was to be mostly cleared for new buildings. A low-lying

receiving block and accident department, flanked by medical and surgical ward

wings, was designed to provide a new public entrance to the hospital. An

operation block was planned for the site of the medical college, adjacent to a

rehabilitation department and surgical wards. Extensions to the Edith Cavell

Home and the Eva Lückes Home were intended to accommodate more than 700

nurses. A scattering of buildings on the hospital’s estate, including St

Philip’s Church and the students’ hostel in Philpot Street, were to be

preserved and engulfed by a series of uniform buildings grouped to provide

distinct quarters for outpatients, inpatients and the medical college.

In the event, inflation put paid to these plans for redevelopment. Post-war

alterations and additions proceeded in a piecemeal manner, based on the

framework set out in the bicentenary campaign. The works department embarked

on numerous alterations in the years immediately after the war. A new

receiving and accident department was formed in the front block, along with

first-floor research laboratories replacing children’s wards on the south side

of the central block. These laboratories were assigned to bacteriology and

industrial diseases. Additional works were carried out in 1952–3,

including the formation of a genito-urinary department, alterations to the

laundry, and the enlargement of the dental division of the outpatients’

department.

The most significant alterations to the main hospital building in the 1950s

were carried out by W. H. Watkins, Gray & Partners, an architectural firm

with substantial experience of hospital work. Watkins, Gray & Partners

worked in association with the hospital’s surveyor R. M. Halsey, who succeeded

Oatley. The upper storeys of the bomb-damaged east wing were rebuilt in

1958–9, followed by a five-storey extension to the west wing to provide

additional wards. Bennett & Son oversaw further alterations to the main

hospital building, along with the construction of the Holland Wing and the

rebuilding of the Alexandra Wing. Leonard Abbott, an associate (1966) then

partner (1973) in the firm, supervised the works due to his specialism in

hospitals. The main public entrance to the hospital was altered around 1969 by

the application of marble cladding. Bennett & Son also developed

proposals for the rebuilding of the hospital on expanded lines, with large

blocks engulfing the eastern side of its estate. This fifteen-year project

aimed to raise the size of the hospital from approximately 750 beds to 1,300

beds by 1972. The scheme was partially realised by the construction of

Knutsford House, the Institute of Pathology, the Princess Alexandra School of

Nursing, John Harrison House, a computer centre, and a cluster of nurses’

homes. The listing of the main hospital building in 1973 thwarted plans for

its redevelopment, and only the Alexandra Wing was rebuilt.

Link Block, 1959–62

The post-war building programme encroached on many of the open spaces

surrounding the hospital. The quadrangle was mostly sacrificed for the Link

Block in 1959–62. This six-storey extension was designed by Watkins, Gray

& Partners in association with R. M. Halsey and consulting engineers Oscar

Faber & Partners. The block provided additional wards and kitchens,

connecting the west and east wings. The upper floors were elevated by a series

of reinforced-concrete piers to preserve a route between the remainder of the

quadrangle and the hospital’s gardens. The north and south elevations

incorporated metal-framed projecting balconies, breaking the monotony of sheer

expanses of brickwork. Single-storey clinics for dialysis and radiology,

flanking the ground-floor passageway, were added by Bennett & Son in

1967–8.

Holland Wing, c.1968

The Holland Wing, named after the hospital’s longstanding chairman, replaced

the southern portion of the Grocers’ Company’s Wing and the Bernhard Baron

Pathology Institute in the late 1960s. This five-storey block designed by

Bennett & Son was described in design stages as a ‘decanting building’, a

name that captured its assorted administrative, medical and teaching

functions. The block was positioned on the west side of East Mount Street,

with brick-clad elevations divided by horizontal bands of glazing and mosaic.

Each floor contained a central north–south corridor, extending from the

Grocers’ Company’s Wing to a lift lobby at the south end of the block. The

internal spaces were divided by partition walls to ensure future adaptability.

A cardiac department was installed in the basement, and the ground floor

contained staff offices and a board room. The first and second floors were

devoted to a maternity department, composed of delivery suites, isolation

rooms, and four-bed wards with ancillary rooms. An intensive neonatal unit was