St Philip's Church Library and the Royal London Museum

Red brick church of 1888–92 designed by Arthur Cawston and converted into a medical library in the 1980s.

Whitechapel Library, Newark Street (formerly the Church of St Augustine with St Philip)

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 1, 2017

The red-brick church that lies behind the former Royal London Hospital was built in 1888–92 to the designs of Arthur Cawston. It is on the site of a chapel raised in 1818–21 and subsequently dedicated to St Philip. Almost islanded by Stepney Way, Turner Street, and Newark Street, Cawston’s church is a commanding landmark despite the abrupt base of its unbuilt tower. The quality of his work culminates in the rich interior spaces of St Philip’s, deemed to be an ‘architectural masterpiece’ by the Gothic revivalist Stephen Dykes Bower.1 St Philip’s was merged with nearby St Augustine’s, Stepney, after the Second World War and declared redundant in 1979. The church was converted into a medical and dental library for the London Hospital Medical College in 1985–8.

Whitechapel Library (formerly the Church of St Philip with St Augustine), view from the east behind the new Royal London Hospital. Photographed by Derek Kendall in 2016 for the Survey of London.

Stepney New Church, 1818–21

The chapel which preceded the present church was at first known variously as Stepney Chapel and Stepney New Church. It was probably dedicated to St Philip the Apostle in 1836, when it was assigned a district from the parish of Stepney. Plans to build a chapel of ease in the neighbourhood of the London Hospital originated in nine Trustees, namely Thomas Barneby (Rector of Stepney), Harry Charrington, Nicholas Charrington senior and junior, William Cotton, William Davis, Charles Hampden Turner, James Peppercorne, and Christopher Richardson junior. Each of the Trustees was prominent in local affairs, business and philanthropy, and nearly all were governors of the London Hospital. Cotton was also an energetic promoter of Anglican church attendance, as a founder of the Church Building Society and a supporter of the Churches Act of 1818. The Trustees determined that, of all the hamlets in Stepney, Mile End Old Town most urgently required a new church. A vacant piece of ground south of the London Hospital and straddling the parish boundary with Whitechapel was deemed to be convenient, being at the heart of a growing neighbourhood in the throes of development. The Trustees set about raising subscriptions towards a new church for 2,000 worshippers that would offer free sittings for two-thirds of the congregation and derive its income from pew- rents.2

For its design the Trustees turned to John Walters, an architect and engineer who, as the surveyor to the London Hospital from 1806, was probably familiar to many of the Trustees. This attribution has been confused by a letter written to John Soane, who had enquired about the size and expense of the church following the Act of 1818. Francis Goodwin, then employed as a clerk in Walters’s office, wrote in October that ‘although Mr Walters was the appointed architect to the Stepney New Church – I had the honour to make the design, and to superintend the building’. This claim may need to be treated with caution, given Goodwin’s later opportunistic pursuit of church commissions.3

The progress of the church was marred by financial complications and its intended size diminished accordingly. Despite commencing building on a ‘limited scale’ in June 1818, when the first stone was laid by the Duke of York, funds were depleted by the end of the next year.4 An application for a grant from the newly formed Church Building Commission secured £3,500 with the condition that the sum would only be paid after the finished church was surrendered to the Commissioners. The promise of an influx of cash failed to distract the Trustees from entering into a legal dispute with their builder, Francis Read of Islington. In May 1816 Read had agreed to build the chapel and install the pews for £6,200 within three years, yet his work was not finished until Spring 1821. During this interlude a number of additional contracts were agreed to cover the cost of the pulpit and interior fittings, raising the contract price to £6,815. Read’s final account of £12,400 surprised the Trustees, who determined that his calculations were ‘in a very incorrect and imperfect state’.5 This startling discrepancy was explained as ‘extras’, and a protracted legal case followed, which concluded in a payment of £2,000 to Read.6

Due to this setback, the finished church stood unconsecrated, dormant, and neglected for nearly two years. Writing in The Gentleman’s Magazine, Edward John Carlos deplored that ‘its windows were broken by idle boys, and its walls made the repository of inflammatory inscriptions’.7 Its site was finally conveyed to the Commissioners in 1822, and the consecration followed in January 1823. Stepney Chapel stood behind iron railings at the centre of an island site bounded by newly formed streets on the London Hospital Estate. This Perpendicular Gothic church was in contrast to the sober neoclassicism of nearby St Paul’s Church in Shadwell (1817–21), built simultaneously to designs by Walters, who had died exhausted in October 1821 at the age of thirty-nine. Stepney Chapel was a brick-built rectangular structure coated with Hamelin’s Mastic, a stucco favoured for ornamented surfaces. The public front in Turner Street was adorned by a large west window above a central entrance flanked by octangular buttresses with pointed spires. Plainer side entrances stood below decorative niches and pierced quatrefoil parapets. This neat tripartite arrangement was replicated at the east front, which contained two vestry doors. The decoration bestowed on the entrance fronts was diluted in the treatment of the side elevations, each composed of six evenly proportioned bays defined by buttresses with crocketted pinnacles. The Gothic window frames were modelled in artificial stone by J. G. Bubb.8

The west front of the church opened into a passage with north and south porches fitted with stairs to the galleries. Beyond the five-bay nave and aisles, the east end terminated in a large traceried chancel window behind a carved pulpit and desks for the reader and the clerk. The recessed chancel was flanked by vestries and the nave arcades were supported by cast-iron columns faced with mastic. The nave was overlooked on three sides by galleries, bestowed at the west end with an organ in a finely carved case. Deal pews decorated with Gothic panels secured 408 sittings, supplemented by 754 free seats. This number was significantly less than the 2,000 sittings first contemplated, and still fewer than the 1,500 sittings calculated erroneously on the working drawings. Judging from J. H. Good’s calculation of sittings in 1840, a proposal to install flaps in the side aisles to raise the capacity to 1,338 was executed.9

Later history and alterations

The smooth mastic coating of Stepney Chapel was not destined for longevity, as in its ill-fated application at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. In a visitation return of 1841, the Rev. Joseph Heathcote Brooks complained that the mastic was ‘all coming off’.10 The condition of the church had worsened considerably by 1858, when the Rev. James Bonwell claimed that it was ‘falling down’.11 Bonwell shocked the neighbourhood as the rakish culprit of the ‘Stepney scandal’ wildly reported in the press. Efforts towards the restoration of the church were deferred until after Bonwell’s dismissal in 1860, when his temporary successor the Rev. J. G. H. Hill arranged repairs and improvements. The arrival of a perpetual curate in July 1862 brought stability and a renewed attempt at restoration. As the son of Charles James Blomfield, the former Bishop of London, the Rev. Alfred Blomfield was a prestigious appointment to a district parish shaken by Bonwell’s misdemeanours. Blomfield established a public appeal for funds to build a parsonage and rectify the failing mastic. The exterior repairs were overseen by James Knight and completed in 1863.12

Blomfield’s promotion in 1865 led to the appointment of the Rev. John Richard Green, who was to gain renown and influence through writing A Short History of the English People (1874). Green arrived at St Philip’s with experience of impoverished east London parishes, namely Holy Trinity, Hoxton, and St Peter’s, Cephas Street. In a letter of 1869 to William Boyd Dawkins, Green described his situation at St Philip’s, and its connection with nearby St Augustine’s in Settles Street:

In plain English, I am incumbent of St Philip’s, Stepney, which the work of Blomfield here has made the ‘crack’ parish of this end of Town. There is a good church, a fine choir, a capital parsonage, and good schools – 16,000 people, of whom 6,000 are cut off to form a mission district. Two curates work with me at the church, two more are in charge of the Mission.13

Green resigned his living due to ailing health in 1869 and devoted the rest of his life to writing. He was succeeded by the Rev. Alexander Johnstone Ross, who heartily started to raise money for a complete restoration of the church. Ross enlisted the advice of E. W. Godwin and contemplated rebuilding, until it became apparent that funds were too scarce. A faculty issued in 1871 authorized restoration works to designs by Godwin. The organ was transferred to the north side of the chancel, effected by removing part of the north gallery, a new pulpit was raised, and choir stalls were installed with distinctive carved ends hollowed into upturned crescents. In 1875 a memorial window was completed to designs by William De Morgan for the social reformer Edward Denison, who had lived briefly in Philpot Street to intensify his work with the poorer classes of east London.14

The restoration of St Philip’s collapsed due to a shortage of funds. The earlier works had been funded by a private loan taken out by Ross, who was increasingly burdened by interest payments. Ross intensified his fundraising efforts, concerned that many of his congregation had ‘been drawn into the handsome dissenting chapel’ in Philpot Street ‘by the dismal condition of the parish church’.15 A catalogue of desirable alterations and repairs in 1876 included the reseating of the nave, aisles and gallery, new windows, and a drainage course to salvage the exterior walls from damp. It is not certain that these works were completed, aside from external repairs and the insertion of a ceiling in the crypt.16

Rebuilding, 1888–92

A rebuilding scheme for St Philip’s Church was precipitated by the Rev. John Sidney Adolphus Vatcher, who found it in a ‘disastrous and disgraceful state’ after his arrival as vicar in 1883.17 Vatcher began to raise funds towards a new church, yet reputedly a substantial contribution was derived from his private wealth, which probably stemmed from his family in Jersey. The foundation stone was laid in July 1888 and construction by A. Bush & Sons was executed in two phases. The east side of the earlier church was preserved temporarily for worship, accessed by an iron entrance porch installed to the south. The west side of the church, including the nave, the aisles, the transept piers and the baptistery, was completed in 1889 and used for worship from the next January. The east end followed in 1890–2, and the finished church was consecrated on 27 October 1892. At this time, it was described by William Sinclair, Archdeacon of London, as a ‘magnificent gift to the Church’ that had ‘cost £40,000 out of Mr Vatcher’s own pocket’.18

St Philip's Church, photographed by Derek Kendall from Newark Street in 2016.

The building is a rare example of the work of Arthur Cawston, a lesser-known architect whose early death in 1894 aged thirty-seven severed a nascent career. Cawston was articled to Habershon & Brock and worked in the office of Edward I’Anson before designing a handful of residential, civic and institutional buildings. Prior to St Philip’s, Cawston had taken only tentative steps in ecclesiastical architecture with the Ascension in Balham Hill (1883) and St Luke’s in Bromley Common (1886). Both red-brick churches bear the plain Early English style adopted at Cawston’s final church, yet lack its imposing scale and grandeur. The ambition of Cawston’s design testifies to the generous brief set by Vatcher, who wished to raise ‘a building worthy of the great purpose to which it is put; an interesting place for the parishioners to rest and hide themselves for a time from their neighbours, and a permanent protest in this practical age against the everlasting question, “Will it pay?”’.19

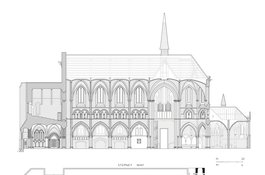

The east end of former St Philip's Church, photographed by Derek Kendall in 2016 after the demolition of the Royal London Hospital's Fielden House and Pathology Block.

The irregular footprint of the church sprawls over more of the site than had been neatly occupied by Walters’s chapel, leaving open spaces for repose. The west end is flanked by small gardens graced by a fig tree and a tall lime tree at the south, and a leafy walled cloister extends along the south side of the church, screened from Newark Street by a tall stock-brick wall. The asymmetrical plan and stark red-brick walls with Ancaster-stone dressings are consistent with Cawston’s earlier ecclesiastical work, yet also recall the manner of the east London churches of James Brooks. Unlike in his earlier commissions, Cawston was presented with the rare challenge of designing an urban church visible from every angle. A plain Early English style was adopted in deference to the austerity of its neighbourhood. The narrow nave is expressed externally by a four-bay clerestory, its other faces concealed by a lively cluster of buildings. The west end is dominated by the unfinished tower, of which only the lower stages were built. A surviving model of the proposed tower by C. N. Thwaite indicates that an octagonal turret was once envisaged, yet Cawston also produced drawings for a sturdy square tower. The exposed corners of the tower are supported by angle buttresses, with a corbelled staircase suspended at the north-west. Its north face is encroached by a gabled porch, intended as the ceremonial entrance to the church yet rarely used. A stock-brick passage in Stepney Way had been added by 1916, yet this route to the hospital is now blocked. The usual entrance to the church has probably always been the stock-brick south porch, originally approached through the cloistered garden. The north and south aisles comprise four bays articulated by brick buttresses and windows, each embellished with dissimilar tracery. The east and west transepts rise to brick gables with vacant stone niches, placed above three lancet windows and a perforated stone parapet. The east end of the church was intended to overlook a public garden, sacrificed in 1899 for hospital expansion by the construction of Fielden House. Its recent demolition has exposed the angular projection of the morning chapel, its plain battlemented walls converging at a central gable with a triple lancet window. A steep flèche marks the crossing of nave and transepts, rising above Welsh slate roofs. The vestry which abuts onto Newark Street seems to have been built by December 1892, despite its omission from early plans. Its plain stock-brick walls climb to high windows and a tiled hipped roof. The east and west elevations bear Gothic entrances, yet it is plausible that the discreet blocked doorway opposite the former vicarage served as the usual entrance.20

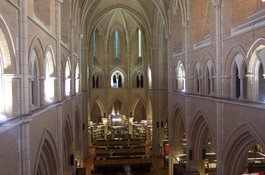

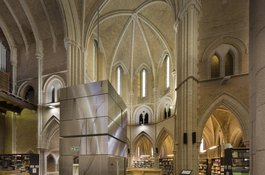

View of the nave from the former baptistery in December 2017. Photographed by Derek Kendall.

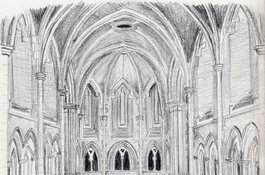

The heavy blocky exterior of St Philip’s cloaks the grandeur and grace of the interior. Vatcher’s aspiration for the church to provide an ‘artistic resting- place’ for his parishioners is manifest in bold vistas generated by stately proportions and stock-brick vaulting dressed with Bath-stone ribs, reminiscent of the work of John Loughborough Pearson.21 The west end is occupied by a baptistery, where the font from the early church was installed, and a barrel- vaulted gallery. The narrow four-bay nave lies between double aisles and rises through a triforium and clerestory to an imposing height. The nave advances to the crossing of the north and south transepts, originally fitted with choir stalls, and culminates in a five-bay arcaded apsidal chancel encircled by a vaulted ambulatory. The chancel arcade affords fragmentary views of the intricate vaulting of the morning chapel, in plan a compact octagon similar to the Lady Chapel at Wells Cathedral. A ground plan of 1887 suggests that the east end was initially to be closer to that of St Luke’s in Bromley, with a long arcaded chancel terminating in a semicircular apse and a rectangular morning chapel adjoining the north transept.22

View of the stock-

brick vaulting over the nave and the chancel. Photographed by Derek Kendall in

2017.

View of the stock-

brick vaulting over the nave and the chancel. Photographed by Derek Kendall in

2017.

The nave was furnished with free seats and contained a marble pulpit with three carved relief panels, including a bust of Dorcas thought to be a likeness of Marion Vatcher, the vicar’s wife. Accessed by an oak spiral staircase, the organ gallery over the north transept was fitted with an instrument built by the Ginns Brothers of Merton, restored by Noel Mander in 1961. In the interval between the completion of St Philip’s and its conversion into a medical library, its interior witnessed few alterations. Stephen Dykes Bower supervised works to the sanctuary in 1949, including repaving with Portland stone and Westmorland slate. This scheme was intended to commemorate the former vicars of St Augustine’s, which had been irreparably damaged by incendiary bombs. The reredos from St Augustine’s, designed by G. F. Bodley, was later transferred to the morning chapel.23

View from the west gallery, looking east towards the nave. Photographed by Derek Kendall in December 2017.

Conversion into a medical library

St Augustine with St Philip’s Church was converted into a library for the London Hospital Medical College in 1985–8 to plans by Fenner & Sibley. Following the assimilation of the college into Queen Mary University of London in 1995, the building continues in use as a medical and dental library.

The formal redundancy of the church in 1979 coincided with concern that the library in the adjacent medical college was overcrowded and inadequate. The disused church fortuitously presented an extensive space at the heart of the London Hospital campus. A feasibility study and plans for its adaptation were prepared in 1982 by William Sibley of Fenner & Sibley, a practice formed by partners in the office of H. Reginald Ross after his retirement. The college’s fundraising appeal won support from a number of benefactors and received grants from the GLC Historic Buildings Division and English Heritage (from 1984) towards the restoration and repair of the church. After the redundancy scheme received official sanction in July 1985, the work was executed in two stages by the highly regarded local builders R. W. Bowman. The first phase covered the restoration of the exterior, including the removal of an extension to the north porch. The next stage of the works witnessed the repair of the interior and its conversion into a library. As a precaution against the weight of books, the ground floor was reinforced with brick piers and structural steel.24

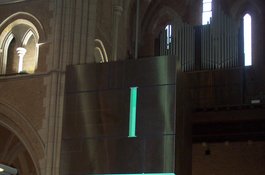

View of the crossing of the nave and the transepts, looking south-east, showing the lift designed by Surface Architects. Photographed by Derek Kendall in December 2017.

The library entrance was transferred to the south-west courtyard, bypassing the walled garden that had originally formed the public approach to the church from Newark Street. The south passage leads to a library issue desk installed in the former baptistery, adjacent to a computer room in the north porch. The west gallery is devoted to historical and rare books. The vestry was converted into staff offices by the insertion of a mezzanine level and light partitions. Early drawings suggest that it was intended from the outset to transform the nave, choir and sanctuary into a dignified reading space, bounded by book shelving in the aisles and the morning chapel. The crossing of the nave and transepts was initially furnished with reading desks, yet has acquired an unusual focal point with the installation of a lift designed by Surface Architects in 2003. The adaptation of the crypt occurred after the opening of the library in September 1988. Comprising only the eastern side of the church from the third bay of the nave, the well-lit crypt has been divided into storage, teaching and computer rooms for the library west, and the Royal London Hospital Museum east. The passageway to the museum, which encircles the former vestry, is lined with Portland stone plaques inherited from hospital wards. Its north side is bordered by a fragment of railings with castellated finials, which probably survive from the earlier church.25

Railings outside the Royal London Hospital Museum in the crypt of former St Philip's Church, which probably survive from the church of 1818–21.

The fittings and furnishings of the church were removed after the approval of the redundancy scheme, with the exception of monuments. The north aisle contains a neoclassical marble tablet to Eva C. E. Luckes, matron of the London Hospital from 1880 to her death in 1919. Other monuments include a slate tablet commemorating the restoration of the sanctuary in 1949, and several memorial plaques. Two tablets in the south aisle commemorate windows installed at the earlier church in 1873.26

An important addition to the library is the distinctive stained glass installed in the north and south aisles in 1999–2002 to designs by the German artist Johannes Schreiter, whose aborted scheme for the Heiliggeistkirche in Heidelberg attracted the interest of stained-glass artist Caroline Swash in 1989. The idea to commission stained glass on medical and scientific themes for the library was derived from her husband Michael Swash, Professor of Neurology at the London Hospital Medical College. The collaboration which unfolded between Schreiter, Swash and medical minds at the Royal London Hospital and St Bartholomew’s resulted in eight stained-glass windows crafted at the studio of Wilhelm Derix in Taunusstein. As described fully in Caroline Swash’s book, Medical Science and Stained Glass, the themes of the north windows are The London Hospital, Gastroenterology, AIDS/HIV, and Ethics, while the south windows comprise Medical Diagnosis, Influenza Pandemic, Molecular Biology, and The Elephant Man.27

The Molecular Biology Window in the south aisle. Photographed by Derek Kendall in December 2017.

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), DL/A/C/02/095/087. ↩

-

Church of England Record Centre (CERC), ECE/7/1/20850/1; LMA, DL/A/C/MS/19224/614; Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 14 June and 28 July 1817; LMA/4441/01/3143; VCH; ODNB; Pevsner, The Buildings of England, London 5: East (2005), p. 392. ↩

-

Soane Museum (SM), Correspondence 2, X.E.3., cited by Michael Port, ‘Francis Goodwin (1784–1835): An Architect of the 1820’s. A Study of His Relationship with the Church Building Commissioners and His Quarrel with C. A. Busby’, Architectural History, Vol. 1 (1958), pp. 61–72; Colvin; Royal London Hospital Archives (RLHA), RLHLH/A/5/14, p. 243; RLHLH/A/5/17, pp. 95–9. ↩

-

CERC, ECE/7/1/20850/1. ↩

-

CERC, BARNES 3/4/10, BARNES 3/2/3/14. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHINV/883; Gordon Barnes, Stepney Churches: An Historical Account (London: The Faith Press for the Ecclesiological Society, 1967), pp. 70–4; LMA, DL/A/C/MS/19224/614; CERC, ECE/7/1/20850/1. ↩

-

‘Account of the New Chapel at Stepney’, The Gentleman’s Magazine (January 1823), pp. 4–7. ↩

-

John Summerson, Architecture in Britain 1530–1830 (1993), p. 439; Colvin; Thomas H. Shepherd, Metropolitan Improvements (1827); Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 3 June 1820; RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/17, pp. 95–99; CERC, ECE/7/1/20850/1; LMA, DL/A/C/MS/19224/614; OS 1873; The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol. 99, Part 2, Vol. 146 (1829), pp. 578–9; ‘Account of the New Chapel at Stepney, The Gentleman’s Magazine (January 1823), pp. 4–7. ↩

-

CERC, CBC/7/1/5, p. 87; SM, Nos 5543, 6799; Thomas Allen, Histories and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southward and Parts Adjacent, Vol. 5, Part 3 (1828), pp. 483–4. ↩

-

Lambeth Palace Library (LPL), FP Blomfield 72/140. ↩

-

LPL, TAIT 440/366. ↩

-

East London Observer, 2 November 1861, 20 August 1862, 24 January 1863, 2 May 1863; 2 January 1864; London Evening Standard, 28 October 1865; LMA, DL/C/A/020/MS11725. ↩

-

Letters of John Richard Green, edited by Leslie Stephen (London: Macmillan, 1901), pp. 159–60. ↩

-

ODNB; The Architect, 23 December 1871; LMA, DL/A/K/09/10/458, Letter by A. J. Ross, 26 October 1876; LMA, DL/A/C/02/v17/014; East London Observer, 22 July 1871, 22 March 1873, 10 April 1875; LPL, No. 7419. ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/K/09/10/458, Letter by A. J. Ross, 28 January 1875. ↩

-

LPL, Jackson 50, f. 103; LMA, DL/A/C/MS/19224/614. ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/02/034/026; LPL, FP Jackson 2/553. ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/MS19224/614; LMA/4441/01/3143, DL/A/C/02/034/026; The Builder, 11 October 1890; 1861 Census; LPL, FP Jackson 2/553; Building News, 28 October 1892, 2 December 1892, 9 December 1892, 23 December 1892; CERC, ECE/7/1/20850/2. ↩

-

The Builder, 17 January 1891, p. 50; 16 June 1894, 11 October 1890. ↩

-

The Builder, 11 October 1890; RLHA, RLHINV/884; Building News, 2 December 1892, 9 December 1892; LMA, DL/A/C/02/045/029; OS 1916; RLHA, RLHINV/143. ↩

-

The Builder, 7 March 1891, p. 193; Historic England Photographic Library, B940812–3, A910644–6, 64/5757–67; 66/3729–30. ↩

-

The Builder, 11 October 1890, 7 March 1891; LMA, DL/A/C/02/039/017. ↩

-

LMA, DL/A/C/02/095/087; Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley and the architecture of the later Gothic Revival in Britain and America (New Haven and London, 2014), p. 450; Historic England Historians’ file TH40, PM 851, January 1979; Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives, P09989, P09992–7, P09995, P10005–6, P10012–3. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/MC/X/38; RLHLH/MC/A/24/127; ‘Book Case’, Building Design Supplement (August 1989), p. 48. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/TH/A/13/8; RLHA, RLHLH/MC/S/4/12; RLHLH/TH/A/13/8; LMA, DL/A/C/MS/19224/614; Information from Richard Meunier, Archivist at the Royal London Hospital Archives & Museum; ‘Ambiguous Object’, PA/03/01267; ‘Surface feels uplifted’, Building Design (27 August 2004). ↩

-

RHLA, RLHLH/MC/X/38; RLHLH/MC/A/24/127; LMA, DL/A/C/02/095/087; LMA, DL/A/C/02/056/027. ↩

-

Caroline Swash, Medical Science and Stained Glass: The Johannes Schreiter Windows at the Medical Library, the Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel (Malvern Arts Press, 2002); Caroline Swash, The 100 Best Stained Glass Sites in London (Malvern Arts Press, 2016). ↩

Historic England list description for St Augustine with St Philip's Church

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London on Aug. 26, 2016

Excerpt from Historic England list entry for St Augustine with St Philip's Church (listed at Grade II*):

STEPNEY WAY E1 4431 (South Side) St Augustine with St Philip's Church (Formerly listed as St Philip's Church) TQ 3481 15/504 29.12.50 B GV 2. 1888-92. Architect Arthur Cawston. Early English style. Red brick with white stone dressings. Lofty building with shingled fleche over dressings. Brick intersecting vaults with stone quoins. Ambulatory arcade to apsidal chancel and apsidal Lady Chapel at east end. Porch at west end is base of a tower which was never built. Good example.

St Augustine with St Philip's Church forms a group with Nos 28 to 42 (even) Newark Street.1

-

Historic England, National Heritage List for England, list entry number: 1065066 (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1065066, accessed 26 August 2016). ↩

St Philip's Church, view from the south-west in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

View from the north-west, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Philip's Church, long section and ground plan - drawing by Helen Jones

Contributed by Survey of London

View of the exterior of the former morning chapel from the south, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

View from the south-west, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Philip's Church, view from the east in 2016

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Brick vaulting over the nave, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

View of the nave, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

View from the former baptistery looking east towards the nave, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

West gallery, looking east towards the nave, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

View of the nave looking towards the north aisle, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

View of the nave, looking west

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The south ambulatory, looking east towards the former morning chapel, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The crossing of the nave and the transepts, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Influenza Pandemic Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The London Hospital Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Gastroenterology Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The AIDS/HIV Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Ethics Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Elephant Man Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Molecular Biology Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Medical Diagnosis Window, December 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

St Philip’s Church, Architectural model, north elevation

Contributed by matthew

St Philip’s Church, Architectural model, view of interior

Contributed by matthew

Monument to Eva Luckes, hospital matron, on the north wall

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

View of the organ

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Monument commemorating the laying of the foundation stone in 1888, on the west elevation

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Plaque for Fitzgerald ward, the Royal London Hospital

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Plaque for William IV ward, the Royal London Hospital

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Plaque for the Richmond ward, the Royal London Hospital

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Plaque for Adelaide ward, the Royal London Hospital

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Plaque for Turner ward, the Royal London Hospital

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Library drawing

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Stained glass window

Contributed by paula

Construction of the ambiguous object

Contributed by paula

Construction of Ambiguous Object

Contributed by paula

Construction of Ambiguous Object

Contributed by paula

Construction of Ambiguous Object

Contributed by paula