Toynbee Hall

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 24, 2018

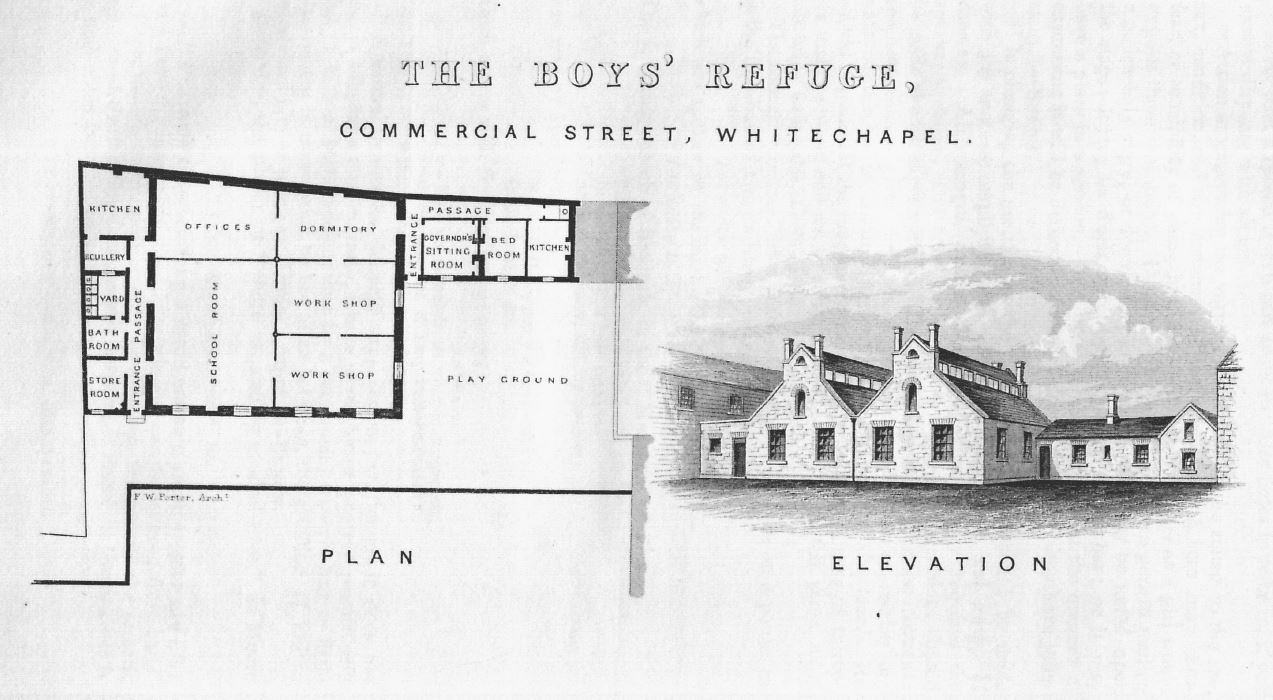

The Boys' Refuge provided a literal foundation for the building of Toynbee

Hall, the first university settlement, which opened in 1884. Samuel Barnett,

the incumbent since 1873 of the neighbouring St

Jude’s,

had since his appointment been pursuing his mission to enable his parishioners

to realise their ‘best selves’ through various pastoral and educational

initiatives. From before his arrival in Whitechapel, Barnett had been involved

in social reform initiatives, as a founder with Octavia Hill of the Charity

Organisation Society, which sought to make sense of the hundreds of diverse

charitable and philanthropic organisations, and to fight against ‘doles’, that

to give ‘indiscriminant charity’ without a means test was further to pauperize

the poor. In Whitechapel he had involved himself in civic as well as

church activities, as a Poor Law Guardian, a campaigner for the adoption of

the Public Libraries Act, and a

founder of the East End Dwellings Company.

All these activities stemmed from Barnett’s mission to break down class

barriers, and belief in the duty of the fortunate, educated middle classes to

share the benefits of their education with the less fortunate, to enable them

to realise their ‘ best selves’, and as a lubricant to mutual understanding

between the classes. For Barnett’s friend Matthew Arnold, it had a particular

cultural flavour, that class consciousness had impeded the goal of ‘sweetness

and light’ and ‘[t]he humanising, the bringing in to one harmonious and truly

humane life, of the whole body of English society’. These ideas had been

maturing among Barnett’s associates since the 1860s, particularly in Oxford,

promoted there by the philosopher T. H. Green, who, although he had abandoned

orthodox Christianity, believed in God’s immanence within the self, that the

discovery of that was the path not just to individual enlightenment but,

pursued, as was the duty of the affluent and educated, by one-on-one personal

connection with the less fortunate, demonstrating by their leadership how

others could realise their better selves as part of a larger community.

One of Green’s pupils and another friend of Samuel Barnett, the historian

Arnold Toynbee, believed in the need for a disinterested elite to ‘give up the

life with the books and those we love’ to help the poor, who must be prepared

to pledge themselves to ‘lead a better life’, as framed by their educated

betters.

Although Barnett’s pursuit of these ideas was to be the best known attempt to

realise these ideas, East London had already attracted others with similar

ambitions. The social historian, the Rev. John Richard Green (1837-83) had

been the incumbent at St Philip,

Stepney in 1865-9, with

similar aims in mind, and the reformer and some-time MP Edward Denison

(1840-70) had gone to live in Philpot Street in 1867 in the belief that only

by living among the working class would a genuine community be created, of men

and women of all classes devoted to a common purpose of social improvement:

‘Build school-houses, pay teachers, give prizes, frame workmen’s clubs, help

them to help themselves; lend them your brains’.

It was in this spirit that from the late 1870s Barnett, chafing ‘against the

constrictions imposed by parish concerns’, began to put these ideas into

practice, encouraging undergraduates and others, among them Arnold Toynbee, to

come and give of their time and education in Whitechapel and, as Henrietta

Barnett put it: ‘we put them to such work as was possible during the

vacations’. In November 1883 Barnett gave a paper in Oxford on ‘University

Settlements in East London’, which set out a more ambitious plan for the

establishment of a settlement house in a poor area of London, which would

become ‘a common ground for all classes’, with lectures, conversations and

receptions which would afford ‘all sorts and conditions of men’ the chance to

come to know each other. ‘[T]houghts and feelings which are now often spent in

vain talks at debating societies will go up to town to refresh those who are

spent by labour, or to find an outlet in action… by sympathy and service to

the lives of the people, settlers would ‘bring the light and strength of

intelligence to bear on their government’.

In December 1883 a committee of Oxford men and London supporters, including

the Liberal MP James Bryce had been set up to realise these aims, funds were

raised, and by February 1884 the decision had been made to set up a settlement

in London, on condition that Barnett be its warden.] That month the Boys’

Refuge building next to St Jude’s was bought for £6,350, the new building to

accommodate ‘rooms for 16 men, classroom for 100, large drawing or

conversation room, billiard room and drawing room’. The Universities

Settlement Association was formally registered in July 1884 as a joint stock

undertaking, its objects being ‘education and the means of recreation and

enjoyment for the people in the poorer districts of London and other great

cities’ and the wider ‘inquiry into the condition of the poor and to consider

and advance plans to promote their welfare’.

It was Henrietta Barnett who offered the name Toynbee Hall for this first

settlement in Whitechapel, a memorial to Arnold Toynbee who had died, aged 31,

in 1883.

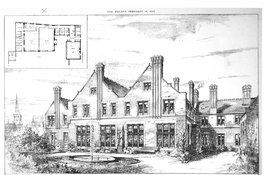

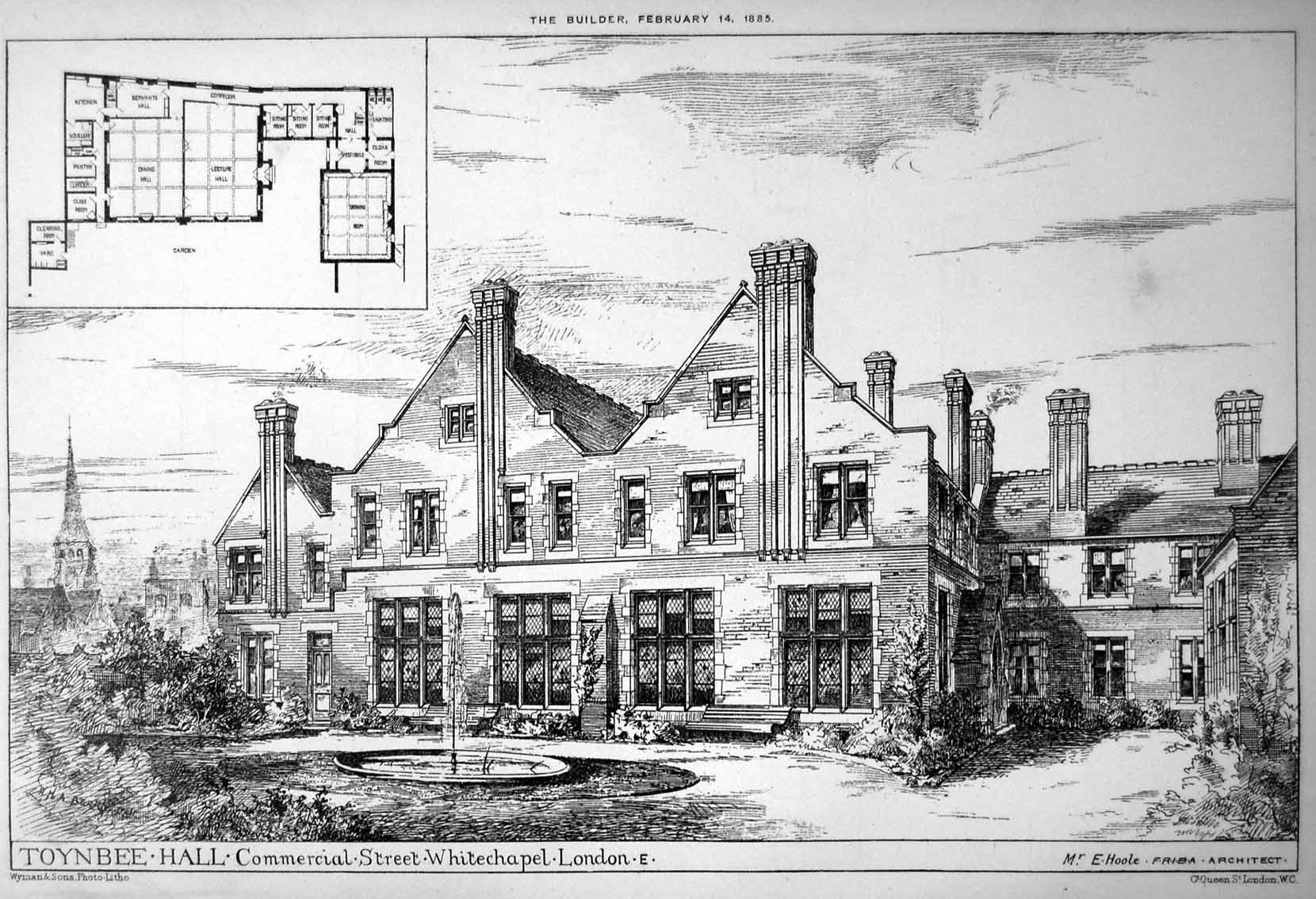

The building of Toynbee Hall was essentially a recasting of the Boys’ Refuge

rather than a completely new building: when the site was acquired, the

buildings were described by Barnett as already ‘half-demolished’. Elijah Hoole

(1838-1912), the Nonconformist London School Board architect, was tasked with

the ‘object of using them as far as possible’ and with producing plans ‘with

the utmost regard to economy’, though the overall cost of the site, buildings

and furnishing and fitting was estimated at £8,000. The workmen started

work on 29 June and, according to Barnett, were to ‘give us a habitable place

by 13 Sept’. Certainly, the work was recorded only as ‘alterations to

Boys’ Refuge’, and the new building followed the footprint, and presumably

used the foundations, of the Refuge, with the settlers’ sitting rooms

occupying the site of the governors’ house, and the lecture hall of Toynbee

Hall occupying the site of the Refuge’s workshops and dormitory, and the new

dining hall on the site of the old schoolroom and offices; the kitchen wing on

the north side was virtually unchanged. Billiards had to wait until the

conversion in 1887 of a workshop into clubroom etc adjoining College

Buildings in Wentworth Street, but a short wing

was built west from the former Boys' Refuge governor’s house site along the

side of St Jude’s with a second entrance and a large drawing room in its own

pitched-roof building.

On the first floor, above the lecture room and dining room, were the rest of

the settlers’ rooms, some two-room sets, others bedsitters, surrounding a

central common room lit from dormers in its pitched roof.

The hall also followed, probably coincidentally, the general disposition of

the Refuge, with steeply pitched gabled fronts to the main building, but its

Tudoresque architectural expression in warm red brick with Box-stone

dressings, stone-mullioned and transomed leaded-light windows and assertively

tall ribbed chimneys, was more aspirational: Barnett called it ‘a manorial

residence in Whitechapel’, but what it resembled more, especially with the

sense of enclosure provided by the gatehouse and the warehouses fronting

Commercial Street, was an Oxford college. Barnett had been in

correspondence with Hoole for some years before this, on the subject of

industrial dwellings, which was soon to bear fruit in Whitechapel in College

Buildings. The style

fitted with commonly held romantic ideas of an ideal communitarian but

hierarchical society existing in the middle ages, and Hoole was himself, at

heart, a Goth.

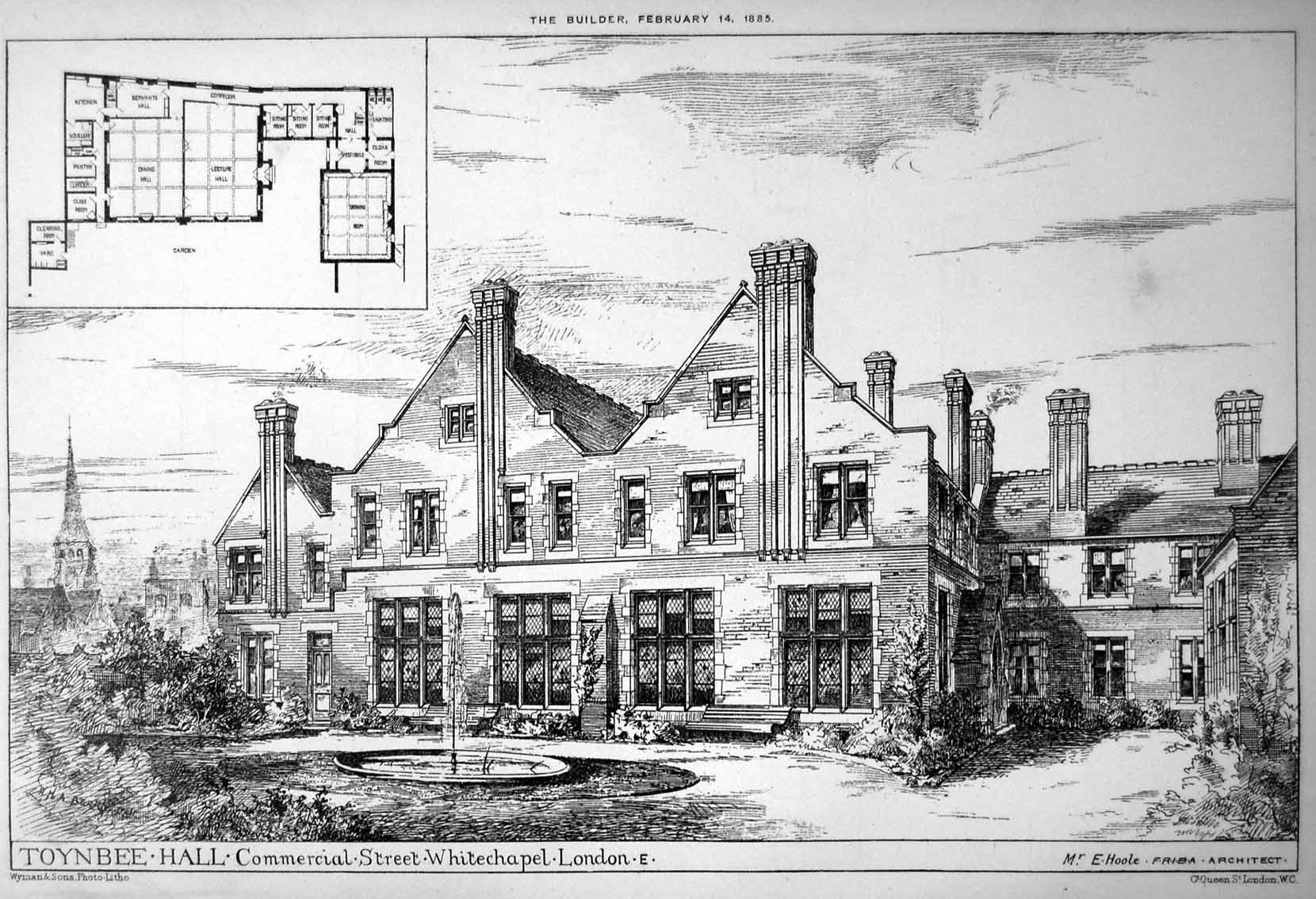

The drawing room at Toynbee Hall

(now the Toynbee Studios

café), c.

1890.

The drawing room at Toynbee Hall

(now the Toynbee Studios

café), c.

1890.

The interior of Toynbee Hall reflected the tastes and ambitions of its

founders. The drawing room was furnished in a mix of Aesthetic and Arts and

Crafts styles, with improving prints and sculpture, the leaded windows draped

incongruously in rich curtaining: ‘we … decided to make it exactly like a West

End drawing room, erring, if at all, on the side of gorgeousness’. The

students’ rooms were more simply furnished but ‘in all rooms neutral drabs

were abolished: Whitechapel needed lovely colours’.

Toynbee Hall staircase,

2018. Photograph © Derek Kendall.

Toynbee Hall staircase,

2018. Photograph © Derek Kendall.

The staircase at the south-east corner was an especial tour de force, the

balusters composed of circular fretwork discs of twining leaves.

The hall’s opening was ‘cruelly delayed’ in Barnett’s view, and the first two

Oxford settlers C.H. Grinling and H.D. Leigh, stayed in Toynbee Hall on

Christmas Eve 1884. The building was not ready to be opened – by the Prince of

Wales - till the end of January 1885, though the settlers’ rooms were soon

filled.

Soon a wide array of classes in history, economics, literature, chemistry,

botany and languages were being offered, along with reading groups and

‘conversaziones’, entertainments, sports clubs and social events where

settlers could invite four ‘pals’ each into the collegiate dining room.

Though the fees – from one shilling – did not preclude anyone but the very

poorest, and evening classes were held for those who had work to attend to

during the day, the level of the teaching, which soon included university

extension classes, was aspirational.

These aims were especially evident in the dining room, decorated by the young

Charles Robert Ashbee, who had arrived at Toynbee Hall in 1886 to teach

classes on Ruskin, despite his reservations that the venture might represent

‘top hatty philanthropy’. At Cambridge in the early 1880s he had come under

the spell of ideas similar to those that had energised Barnett in Oxford. His

was an avowedly non-Christian world view, but in a similar vein to that of

Barnett and T.H, Green; he came, in Alan Crawford’s words, ‘to look on all

material things and the manifold details of experience as the revelation of a

deeper spiritual reality’.

But Ruskin meant also, to Ashbee as to so many idealistic architects of his

generation, a veneration for the materials of building and the free will of

the workman in working them, as well as a horror for the industrial system and

its dehumanising division of labour.

Soon Ashbee and his Ruskin students were putting what they read in to practice

in the dining room, in 1887 adding plaster medallions of a stylised tree and

T, for Toynbee Hall, designed by Ashbee; around these discs were painted

sunflower leaves. Painted plaster coats of arms of Oxford and Cambridge

colleges ran in a frieze around the tops of the walls.

Ashbee had developed, too, from discussions with Edward Carpenter, a notion of

manly comradeship, the common humanity beneath the differences of class. It

was in this spirit that he founded the Guild and School of Handicraft, its

first premises on the top floor of a converted warehouse at 34 Commercial

Street, beside the entrance to Toynbee Hall.

The idea was for the Guild to operate as a commercial concern, making ‘simple

but high-class work in wood and metal’, the workmen also to teach their skills

to apprentices. Ashbee had consulted William Morris, whose firm Morris

Marshall Faulkner & Co, founded nearly thirty years earlier, can be seen

as a model at least in artistic terms, and whose romantic ruralist vision of

medieval England as a civilised communitarian utopia had enraptured a

generation of idealistic young architects and designers. But Morris was

discouraging. By the time Ashbee called, Morris was convinced that only the

overthrow of society by revolution could sweep away its ills; art schools,

even on comradely terms, were pointless. Ashbee never reached that point,

believing in an evolutionary not a revolutionary path.

But Ashbee was tiring of Toynbee Hall, as some others had, because of its

cloistered unreal atmosphere. The success of the Guild also meant he needed

bigger premises, and in 1891 he moved to Essex House in Mile End Road, and in

1902 on to Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds, to begin another chapter in the

Arts and Crafts story.

Toynbee Hall continued to evolve. By 1886 one of the worst slums locally, New

Court, adjoining east to Toynbee Hall, had been pulled down as part of the

Flower and Dean Street Improvement and on it its site were built an extension

to St Jude’s National

Schools,

College Buildings and a tennis court. In

1886-7 a three-storey library wing, including a laboratory, with spiral

staircase in a corner tourelle and an open cloistered ground floor, was added

by Lathey Bros, builders, at the hall’s northwest corner.

In 1892 a cloister-like brick colonnade between the gatehouse and the drawing

room was added, with a picturesque tile-hung clock tower atop it, paid for by

Bolton King, a long-term Toynbee resident, financial supporter and Secretary

of Toynbee Hall. Barnett, having resigned as incumbent of St Jude’s, moved

next door to the gatehouse building, converted into a Warden’s Lodge by Elijah

Hoole, with an imposing oriel window added on the first floor overlooking

Commercial Street.

By the early twentieth century the Barnetts were less involved with day-to-day

life at Toynbee Hall, preoccupied, among other matters, with the creation of

Hampstead Garden Suburb, and Samuel resigned as Warden in 1906. There was

already a shift in the tone at Toynbee, a recognition of the greater role

other organisations had to play in social reform, and Barnett promoted the

participation of trade unions, encouraging them to hold their meetings there.

Even Barnett came to accept, as Arnold Toynbee had before him, the essential

role of the state in achieving social reform. By the time William Beveridge

arrived as sub-warden in 1903 the tone was shifting further. Beveridge

disliked ‘soup kitchens and genial smiles for the proletariat’, and wished to

make it a centre ‘for the development of authoritative opinion on the problems

of city life’. This echoed one of the founding tenets of Toynbee Hall,

that of ‘inquiry into the condition of the poor’, one that had been pursued in

the form of Charles Booth’s magisterial surveys of London labour and the poor,

and of religious life, many of whose assistants, notably Ernest Aves, were

based at Toynbee Hall. Another assistant on and off for around ten years

from the early 20th century was Clement Attlee, the future prime minister who

was to bring Beveridge’s plan for the welfare state into existence after the

Second World War, the most ample realisation of Barnett’s hope that Toynbee

should act as the crucible for the country’s future leaders.

The settlement model had found traction elsewhere, however. By the First World

War there were twenty-seven residential settlements in London, thirty-nine

throughout the country, and the movement was represented internationally

notably in the United States (where there were 400 settlements alone by 1913),

France, Japan and the Netherlands.

Times were changing and Toynbee Hall changed with them, notably under the

successful wardenship in 1919-54 of ‘the most popular man east of Aldgate

Pump’, James Joseph Mallon, a trade unionist and some-time would-be Labour MP

from an Irish working class background in Ancoats in Manchester. Mallon’s

success was due perhaps to his congenial character and a background that

enabled him to relate more easily to the local population. His initiatives on

sweated labour, public order, education and hire purchase while he was at

Toynbee Hall influenced several Acts of Parliament. But it was his cultural

interests, reflected in increased music, dance and drama activities in Toynbee

Hall that drove the alterations and extensions to the buildings which were

showing their age by the 1930s.

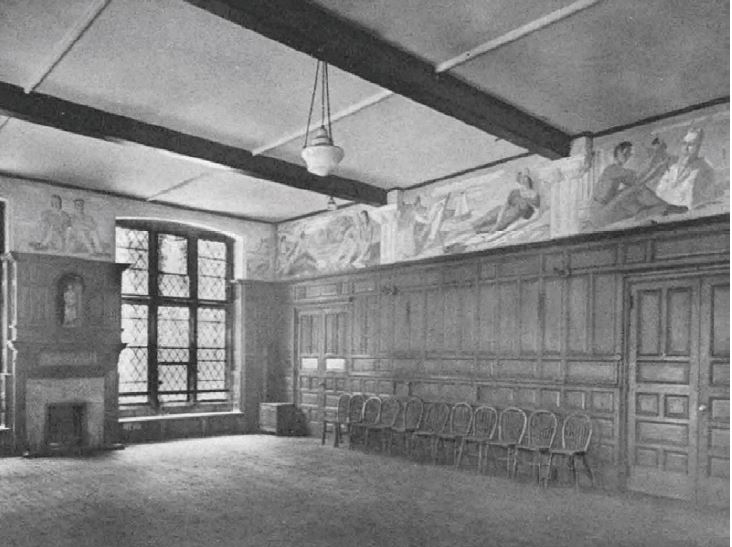

In 1931 a young artist, Archibald Ziegler, heard that J. J. Mallon was seeking

designs for mural paintings to occupy the frieze above the oak panelling in

the lecture hall. Ziegler (1903-71) was an East Ender who studied at the

Central School of Arts and Crafts and won a L.C.C. scholarship to the Royal

College of Art after a spell at sea as a cook. He was given the job at Toynbee

Hall on ‘house painter’s wages’, and the panels, on the theme of the arts and

sciences in a pastoralist manner reminiscent of Stanley Spencer, were

completed in December 1932.

The Ziegler murals in Toynbee Hall from the Illustrated London News, 24 Dec

1932

They depicted, clockwise from the south (entrance) wall: drama, folk dancing;

west wall: bathers, lute from part of the music panel; north wall: music,

painting, sculpture, literature; and the east wall: locomotion, astronomy,

zoology and, native industries’ (which turned the corner ending on the south

wall).

The war saw a curtailment of normal activity as Toynbee became a centre for

distribution of food donated from Petticoat Lane, blankets and clothing,

organising rehousing for those made homeless in the Blitz, and from 1941,

opening the Toynbee Restaurant supplying 600 meals a day. On 10 March 1941

incendiary and high-explosive bombs gutted the library at Toynbee Hall, and

the whole of the Commercial Street frontage enclosing Toynbee Hall, including

the 1840s former St Jude’s vicarage at 26 Commercial Street, and the Warden’s

Lodge, destroying a lifetime’s papers and possession of J.J. Mallon, and four

of the five 1860s warehouses at 30-36 Commercial Street. Despite this, even in

1940-1, the student enrolment at Toynbee Hall never fell below 500 during the

war. The buildings were cleared after the war, except for the surviving

ground floor of the library, used variously as cinema room and offices in the

1950s and rehearsal rooms in the 1960s. With the land gifted by the L.C.C., a

simple garden, partly sunken, reflecting the basement level of the former

street-side buildings and known from the mid 1950s following Mallon’s

retirement, as Mallon Garden, later Mallon Gardens, was created, opening up

Toynbee Hall to the bustle of Commercial Street.

Mallon finally retired at the age of 80 in 1954 and the new Warden, A.E.

Eustace, was appointed largely to report on Toynbee’s future role. The war had

accelerated the shift at Toynbee from academic education, by then largely seen

as the province of the London County Council, to recreational classes

(languages, music and dance, and drama, notably) and social work, in the

context of the new welfare state, that aimed to refocus on the local

population, and the increasing number of paid administrative staff to run the

activities brought into question the residential character of the enterprise,

with many of the small number of residents who had come since the war seen as

regarding it as ‘a friendly “boarding house”, conveniently near to the

City’. After much soul searching it was decided that it was still

valuable to have residents (not least because they could take on some tasks

then undertaken by paid staff, thereby reducing the substantial debt) but that

they should be more carefully picked (not necessarily from Oxford and

Cambridge) for their commitment to Toynbee’s values, and that there should be

renewed efforts to encourage social contact among older and younger users of

Toynbee’s services. Some could perhaps reside in the four blocks of flats

surrounding Toynbee Hall that the association still owned, and help run the

Neighbours’ Club which had come into being for tenants. A likely new use as a

centre for the training of social workers foundered, partly on account of the

dilapidated buildings, and the Mary Ward Settlement in Bloomsbury was chosen

for this instead.

A new Warden with international links, Walter Birmingham, arrived in 1963 just

as Whitechapel’s demographic was once again shifting. Where Barnett had been

at pains to stress the openness of Toynbee Hall to its Jewish neighbours,

Birmingham now launched a booklet Our East London designed to counter

‘racial and religious’ intolerance. In 1965 a Workers’ Education centre

was set up at Toynbee Hall to assist new arrivals, mainly from the Indian

subcontinent, East Africa and the Caribbean, and the Campaign against Racial

Discrimination found accommodation at Toynbee Hall ‘on a generous basis’.

An important event in the stabilisation of Toynbee Hall as an institution was

the arrival as a volunteer in 1964 of John Profumo, the former Secretary of

State for War, who had resigned the previous year over a sexual scandal.

Profumo energised fundraising and secured Toynbee Hall’s future, with promises

of £150,000 by 1967. In 1965-7 a new building to the designs of Martin and

Bayley, architects, incorporating offices and a Warden’s flat, and

accommodation for ‘junior residents’, adolescents recently arrived in London,

and known as The Gatehouse, was finally built on the site of its bombed

predecessor. It was a utilitarian three-storey-over-basement concrete-

framed block faced in reddish-brown brick, the ground floor recessed along its

north side to create a covered walkway like its predecessor, and a separate

entrance along the south side to the Theatre; in 2006 it was renamed Profumo

House in recognition of Profumo’s 40-year contribution to Toynbee Hall.

The regeneration of Toynbee Hall and its estate, 2013-19

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 30, 2018

By the early 21st century Toynbee Hall was once again questioning the

financial viability of its activities, in the context of a historic inner

London building, Grade II Listed since 1973, surrounded by buildings that had

accrued piecemeal in the second half of the 20th century.

The decision was made in 2013 to redevelop its estate at a cost of £17m,

partly from borrowing, partly by fundraising (Heritage Lottery Fund, the

National Lottery, the Garfield West Foundation and the Coutts Foundation, the

principal benefactors) and partly by a partnership with a private developer,

to take a lease on the sites of Attlee and Sunley Houses and College East, by

then leased to One Housing, and rebuild them as mixed tenure housing and

offices. The scheme is forecast to enable Toynbee Hall to increase the

number of those it can assist, with legal and debt advice, wellbeing, notably

for the elderly, and education in a year by fifty per cent, to 20,000.

The initial scheme prepared by CMA Planning consultants with Richard Griffiths

conservation architects, approved in March 2015, proposed restoring and

extending Toynbee Hall, altering rather than demolishing Attlee House,

building two extra floors on top of Profumo House, and adding a new building

on the north side of Mallon Gardens adjoining No. 38 Commercial Street.

The first works in 2016-18, with Thomas Sinden as main contractors, were to Toynbee Hall

itself, by then somewhat scruffy and with ad hoc partitions and fire doors in

many rooms. As well as restoring the fabric, notably Hoole’s leaf-roundel

staircase balusters which had shed a lot of leaves over the years, the scheme

replaced single-storey 1970s additions to the rear housing kitchens, WCs and

an archive room, with a two-storey addition in brick matching the original

building, attached to the existing building by a top-lit corridor, which on

the ground floor features a permanent exhibition about Toynbee Hall’s history.

This aimed to improve access and circulation, the ground floor intended for

conferences, education and functions, with breakout rooms off the Ashbee Room

(the former dining room), and another multi-purpose room, clad in painted

matchboarding in place of the 1970s kitchen on the west side.

The new west elevation has four striking double-pitched gables with bronze-

finish zinc cladding behind a full-width balcony off a new first-floor rear

room.

Two staff flats for were created on the first and second floors. A new more

visible entrance, in place of that directly into the lecture room, led into

what had been student sitting rooms on the ground floor. Upstairs later

additions were removed, and the small student rooms opened up into larger,

more usable spaces, though retaining the original corner fireplaces which

bring a curiously Cubist articulation to the rooms.

A distinction was made in the decoration of the relatively untouched historic

portions, which feature deeper ‘Victorian shades’, and the pale new and newly

created spaces. During works the Ziegler murals from the lecture rooms were

discovered in situ, the boards on which they had been painted merely turned

round during previous works, probably in the 1970s. They are in store pending

conservation and reinstatement. Toynbee Hall’s refurbishment was completed in

July 2018.

A revised scheme for the rest of the site was approved in 2016 with London

Square developers, founded in 2010, as the partner for constructing the flats:

the building next to 38 Commercial Street was omitted and a new building, five

floors with a top-floor setback replicating the Profumo Building’s colonnade,

to house offices and the Toynbee advice service, was proposed for the site of

Profumo House.

The flats, like the new Profumo House, to the designs of Platform5 architects

in collaboration with David Hughes Architects, roughly follow the footprints

of Attlee House,

College East and Sunley

House,

demolished in 2016, with the exception of the retained frontage of College

Buildings, which was retained once again.

The new flats, with Togher Construction Ltd as main contractor, are five and

six storeys on the Wentworth Street frontage, whose façade mimics the rhythm

of College Buildings, with three-window-wide sections alternately four and

five storeys high, the whole with a set-back fully glazed sixth floor, further

articulation achieved through different shades of facing brick from beige to

black, recessed balconies on the Wentworth Street frontage and projecting

balconies on the four-storey Gunthorpe Street frontage.

The scheme is increasingly unusual, though appropriate to Toynbee Hall’s

ethos, in fully integrating the affordable housing (14 flats out of 63) into

the scheme, though the names of the blocks – Leadenhall (Attlee site),

Billingsgate (College East) and Broadway (Sunley) indicate the City-focused

aspirations of the developer. Mallon Gardens is to be landscaped level with

the street for the first time ‘as the centre of a model urban village with a

strong physical and visual relationship to the heritage asset and the wider

Toynbee Estate’. The project is scheduled to complete 2019.

The drawing room at Toynbee Hall

(now the

The drawing room at Toynbee Hall

(now the  Toynbee Hall staircase,

2018. Photograph © Derek Kendall.

Toynbee Hall staircase,

2018. Photograph © Derek Kendall.