The Sailors' Home to 1862

Contributed by Survey of London on March 1, 2019

The Sailors’ Home, also known at first as the Brunswick Maritime

Establishment, was built on the site of the Royal Brunswick Theatre in 1830–5

with Philip Hardwick as its architect. Enlarged to Dock Street in 1863–5,

substantially altered in 1911–12, rebuilt on the Dock Street side in 1954–7,

adapted to be a hostel for the homeless in 1976–8, and again converted to be a

youth hostel in 2012–14, this has been, mutatis mutandis, a major local

presence for nearly two centuries, all the while used as a hostel. As the

first purpose-built short-stay hostel for sailors anywhere, it represented in

its original form the invention of a building type, the Royal Hospital for

Seamen in Greenwich notwithstanding. It was to have seminal influence on the

development of lodging-house architecture.

The prevalence of sailors in east London’s riverside districts was not new at

the beginning of the nineteenth century, but populations did increase and

living conditions declined. The new wet-dock system meant sailors had to leave

their ships immediately without ready access to land-based employment, as

there had been previously. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 left an

estimated 100,000 seamen redundant from the Royal Navy. The Rev. George

Charles ‘Boatswain’ Smith (1782–1863) came to the fore in addressing the lot

of these sailors through evangelism. A seafarer himself in his teens who had

served with distinction under Nelson in the battle of Copenhagen, Smith had

become a Baptist missionary. He established a floating sanctuary on a

remodelled sloop in the Thames off Wapping Stairs in 1818, and the British and

Foreign Seamen’s Friend Society and Bethel Union in 1819. He then took the

former Danish Church in Wellclose Square in 1825 for use as a Mariners’

Church. In the same year Anglicans established the London Episcopal Floating

Church Society, which acquired another ship for seamen to use for worship.

Smith, a witness to extreme poverty and deprivation in and around Wellclose

Square, was next instrumental in establishing an asylum for destitute sailors

in a warehouse in Dock Street, which opened in January 1828. He was in

addition a pioneering advocate of temperance.

Paid upon coming ashore, sailors, both naval and mercantile, were prey to

exploitation and theft by boarding-house and brothel keepers and others, a

practice known as ‘crimping’ that was widespread and generally tolerated.

Smith was determined to force reforms and had tried to introduce a system of

approved boarding houses as used in other ports. In his eyes the Royal

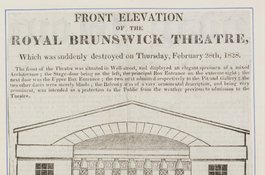

Brunswick Theatre and its predecessor had been a haven for crimping. The

collapse presented an opportunity. In September 1828, just six months on from

the disaster, Smith convened a meeting on the site with a view to raising

there ‘a General Receiving and Shipping Depot for Mariners’. This was to

be a religious mission, aiming at moral reform through reducing the influence

of prostitution and drink. As such it was a late example of the Georgian

impulse to ‘improvement’ and control through institutional architecture.

Alongside Smith were Captains Robert and George Cornish Gambier, RN, brothers

and nephews of Admiral James Gambier, himself an evangelical, and Capt. Robert

James Elliot, RN, who was also a topographical artist. George Gambier was the

Secretary of the London Episcopal Floating Church Society and he and Elliot

were directors of the Destitute Sailors’ Asylum. A committee was formed tasked

with acquiring the ground from the creditors of Maurice and Carruthers. The

Sailors’ Home or Brunswick Maritime Establishment, so-called, launched appeals

in early 1829, aiming to unite ‘the Regularities of social Order with the

moral Decencies of Life, the Principles of Christian Loyalty, and the Duties

of Religion.’

Within the year eminent naval and other figures had been recruited to promote

fund-raising (first trustees included William Wilberforce) and the freehold of

the site was obtained. But Smith, an uncompromising and combative character,

fell out with George Gambier, the Treasurer, over the latter’s unworldly

sympathies for Henry Irving’s radical Nonconformity that led him to leave

fund-raising to faith. Smith stepped down as Secretary and set up a rival

Sailors’ Rest project leading other Dissenters to withdraw support for the

Home. Elliot took charge as the Home’s Secretary, contributed more than £1,000

of his own money, and steered the project into Anglican safety, securing the

patronage of the Bishop of London, Charles James Blomfield. Hardwick was

engaged and on 10 June 1830 Elliot laid a foundation stone. Hardwick conceived

the project in stages, to be built gradually as funds became available,

ultimately to provide space for 500 men, each with their own cabin or sleeping

place. Progress was slow. By the end of 1831 a brick carcase had been raised

and roofed, but there things stalled for want of money, in part because of

Smith’s rival project, which collapsed in 1832, and another short-lived

competitor on Well Street opened by the Destitute Sailors’ Asylum, but

abandoned in 1833. There was also an enforced diversion into the forming of a

sewer extending beyond the site. Basement vaults and other main internal

structures were formed in late 1833, and the Home opened on 1 May 1835 with

accommodation for 100 men on its lower levels, and more than £2,000 still

needed for completion. The first sailors admitted were the crew of an American

ship in St Katharine’s Docks. A peaceful atmosphere introduced by the

‘sobriety and steadiness’ of these ‘temperance men’ was broken a few days

later by the arrival of English sailors, coming from India and bringing

‘intoxication, swaggering and noise’.

The Sailors’ Home was originally a three-storey, basement and attic brick

building facing Well Street. Stucco dressings included channelled rustication

to the ground floor, as survives. This and the bay rhythm of the façade were

retained from the theatre, it is possible even that the lower-storey wall to

Well Street was not wholly rebuilt. Hardwick connected the outer bays with a

portico of large cast-iron Doric columns similar to those he had placed at St

Katharine’s Docks. The south end of the building was replaced in 1893–4, an

additional floor was inserted in 1911–12, and the columns were removed in

1952.

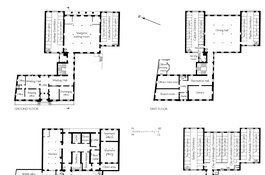

The basement had a kitchen to the north and baggage stores for sailors’ chests

and bedding to the south, central vaults being for general storage and

domestic offices. The main central space at ground-floor level was a waiting

hall open to all seamen. It had a York stone-flagged floor with a grid of nine

tall cast-iron columns. The floor and columns are both still partly extant,

but concealed. This hall was also used for assemblies and worship, and had

small box offices for payment and registration, where the men’s ‘characters’

were recorded. Flanking dormitories named ‘Bombay’ (north) and ‘Calcutta’

(south) had two tiers of cabins either side of passages with rows of

lavatories at one end. The cabins, each about 8ft long, 5ft wide and 7ft high

(2.5m x 1.5m x 2.2m), probably drew on the precedent of Greenwich Hospital’s

accommodation for naval pensioners. On the originally comparably tall first

floor a central dining and reading hall had a similar array of columns and was

flanked by two more double-tiered dormitories (‘Canton’ north and ‘Madras’

south). Upper floors were initially used for a school, lecture room and museum

of ship models and curiosities. As inmate numbers grew in 1842–8 the outer

upper-storey rooms were gradually fitted up as single-tier dormitories,

dedicated in honour of donations as ‘Royal Adelaide’, ‘City of London’, ‘City

of Edinburgh’ and ‘Sydney’, increasing the Home’s capacity to 328. The central

second-floor room remained divided as a navigation school and a boardroom

containing the museum. There was provision for a small savings’ bank, a

shipping office (to get sailors placed on vessels), a library and a chaplain.

A single bath was introduced in 1845. The Home also employed outdoor agents or

runners to outmanoeuvre crimps and bring sailors from their ships.

Henry Mayhew, in a full description that was not uncritical of the Home’s

management, noted in 1850 that seamen addressed the institution’s officers as

friends not as superiors, and recorded a testimony from one among them that

‘the steadiest-going seamen will always speak well of the Sailors’ Home’.

Henry Roberts, closely familiar with the Home having acted as its architect in

the 1840s when he was also the first architect of the pioneering Society for

Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes and responsible for model

lodging houses, later acknowledged that the Sailors’ Home ‘must in some

respects be considered the prototype of the improved lodging-houses.’ The

Home’s achievements notwithstanding, its Chaplain, the Rev. Robert Hall

Baynes, worried in 1858 that ‘the neighbourhood abounds in gin-palaces and

prostitutes, the latter to a fearful extent.’

Annual numbers of boarders rose from 528 in the first year to 1,263 in the

third, 2,183 in 1840 and 3,833 in 1842. Steady increases continued, to 5,544

in 1853 and 8,617 in 1861. Most of the sailors were of British or North

American origin, but not all. By 1862 there had been 544 boarders from

Africa.

The land and the gas house behind the Sailors’ Home had been leased in 1842

with a view to possible extension, even before the formation of Dock Street

and the building there of St Paul’s Church. It was used as a skittle ground.

Part of the new Dock Street frontage was secured in 1854 and the notion of

enlargement was revived as inmate numbers continued to increase. The freehold

of another northerly frontage on Dock Street frontage was acquired in 1859,

but more southerly ground proved slower to obtain, a lease not being secured

until June 1862 – the freehold was purchased in 1889.

The Sailors' Home from 1862, with hostel conversions (1976–8 and 2012–14)

Contributed by Survey of London on March 1, 2019

In late 1862 a building committee took the Sailors' Home's extension plan

forward and Edward Ledger Bracebridge, a Poplar-based architect who had been

responsible for the Strangers’ Home in Limehouse (1857), and who was

personally known to Lord Henry Cholmondeley, the committee’s Chairman, was

appointed with a brief to design a new block facing Dock Street and to

reconfigure the 1830s building. The Rev. Dan Greatorex, newly appointed

Chaplain and a member of the committee, objected to Bracebridge’s first scheme

on account of its impact on light to his house, immediately to the south on

Dock Street. A significantly more expensive amended scheme (first estimated at

£8,000 as against £5,500) was approved and built in 1863–5, with James Mugford

Macey as builder for a contract sum of £10,626. Thomas Wayland Fletcher was

the Clerk of Works. Lord Viscount Palmerston laid the foundation stone on 4

August 1863 and the Prince of Wales opened the building on 22 May 1865. A

commemorative stone plaque bearing that information is still to be found

facing the hostel’s internal courtyard where it was moved, recut, in 1956.

In the earlier block’s basement, the kitchen was enlarged and a scullery

replaced a staircase that had risen through the main halls, now opened up by

the removal of ancillary functions to the new block and the placing of an

open-well stone fireproof staircase in a linking range. The original central

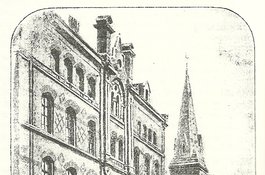

upper-storey spaces were adapted to be more dormitories. The outwardly Gothic

and polychrome Dock Street building’s basement had a room for the navigation

school, a recreation room, two baths and service rooms. The ground floor had

offices to the front, including the seamen’s savings’ bank, with waiting halls

to the rear, the first floor a boardroom and officers’ mess room to the north,

and a library and recreation hall to the south. The two upper storeys were

laid out as a single room, the Admiral Sir Henry Hope Dormitory (Hope, who

died in 1863, had been the Home’s Chairman from 1851). This extraordinary

space comprised four galleried tiers of sleeping berths or cabins (108 in all)

to east and west of an atrium open to the roof with south-end staircases. The

gain in accommodation was 160 berths for an overall capacity of 502. Behind

the new block a basement-level courtyard gave access to an enclosed skittle

alley abutting the earlier building’s northwest corner. A range of water

closets ran alongside another yard behind the vicarage.

In 1874–5 the single-storey skittle alley was reconstructed, extended to the

south and raised to be a three-storey and basement range (which survives) to

provide an additional dormitory for ships’ mates and space for a clothing

store, sales of clothing from the Home having increased since their

introduction in 1868. John Hudson and John Jacobs, both of Leman Street, were

architect and builder respectively. The same men combined to give the 1830s

building an additional attic dormitory in 1876. A drinking fountain still in

situ near the northwest corner of what was the main waiting hall is surmounted

by an inscribed plaque recording a benefaction of 1873 from William McNeil, a

formerly resident seaman. There is also documentation of a drinking fountain

given by John Kemp Welsh in 1875. Thereafter an Officers’ Smoking Room went up

on the north side of the yard.

By this time there were many other hostels for sailors, but the Sailors’ Home

was the parent exemplar. Outside, crimping was still prevalent, and the Home

was drawing more than 10,000 boarders annually. Ale was served, but there was

no bar. It remained a Christian foundation, but not zealously so, aiming to

‘encourage habits of decorum, economy, and self-cultivation, and to contribute

in educating {seamen} as missionaries of Commerce to the ends of the

earth’. Between 1879 and 1884 Joseph Conrad (Jozef Korzeniowski) stayed

several times at the Home and studied in its navigation school. Conrad called

the Home a ‘friendly place’, ‘quietly unobtrusively, with a regard for the

independence of the men who sought its shelter ashore, and with no ulterior

aims behind that effective friendliness.’

Educational provision was reshaped in 1893 in collaboration with the London

County Council, which had a new role overseeing technical schools, to create

the London Nautical School and the London School of Nautical Cookery, to train

cooks for the merchant navy. After the Merchant Shipping Act of 1906 made

certified cooks compulsory, Lloyd George reopened the enlarged cookery school

in 1907.

The Black Horse public house, originally at what became 10 Well Street, had

been extended around 1860 with premises immediately north of the Home’s Dock

Street site. George Edward Rose was the proprietor (it was later the Rose

Tavern), and Frederick Robert Beeston was probably his architect. The Home

acquired this on a long lease in 1895 for conversion to a cartage depot after

the Mercantile Marine Office on Well Street had displaced the establishment’s

earlier stable yard and the original building’s south range.

That sacrifice had reduced the Home’s capacity to 300, a limit that had

further to be reduced to 200 following a threat of closure in 1910 when the

LCC stipulated improvements to the original dormitories, in particular for the

provision of light. An appeal for funds was launched and Murray, Delves &

Murray, architects (Stanley Delves, job architect) prepared plans for works

carried out in 1911–12 by Harris and Wardrop, builders. These involved the

insertion of an additional floor in the Well Street block with internal

reconstruction to form a light-well above the ground-floor waiting hall, which

gained a skylight and was now designated ‘the Lounge’. Structural steel

carried down to the basement. The dining hall moved to the ground floor of the

north range and the cookery school to the skylit attic (until the 1930s when

it moved to the basement). Bars and a first-floor chapel were introduced and

the navigation school soon departed. All the sleeping cabins were now on the

upper storeys. No. 14 Well Street was acquired and demolished to permit the

formation of windows in the Home’s north flank wall, which was faced with

channelled rusticated render. External fire-escape staircases were also added.

Following this reconfiguration the establishment rebranded itself,

incorporating as the Sailors’ Home and Red Ensign Club in 1912.

Despite the reduced berths, the numbers of boarders continued to average more

than 10,000 a year. By 1919 the Home had admitted a total of 639,005 sailors,

336,088 of them English, 51,388 from Sweden, Norway and Denmark, 18,500 from

Germany, 11,376 from Russia, 2,483 from the ‘Cape and Mauritius’, 1,154 from

West Africa, 7,958 from the West Indies, 2,523 from the East Indies, 1,914

from South America, and 1,387 from China and Japan. After this the origins of

the sailors were no longer recorded in annual reports.

Numerous minor alterations were carried out in the 1930s, including conversion

and refenestration of the clothing store for staff cabins in 1931 to raise

capacity to 235. More than 20,000 were boarded in 1933, usage that was

sustained after the war when the merchant navy reserve pool was introduced,

bringing seamen greater security of employment. Additional accommodation being

needed, the Home’s architect, Colin H. Murray of Murray, Delves, Murray &

Atkins, advised a comprehensive approach in 1937 and was asked to prepare

plans for complete rebuilding. War meant postponement, but Murray did advance

a scheme for rebuilding the Dock Street building in 1942.

By 1945 Murray was working with Brian O’Rorke on a more ambitious phased

project for the replacement of the whole complex (now simply called the Red

Ensign Club). This envisaged three slab blocks laid out on an offset H plan to

make best use of the two street frontages, rising at the centre to twelve

storeys for a total 307 bedrooms (no longer called cabins) above lower-level

common spaces. London County Council approval was secured, but in the post-war

years building licences were not forthcoming. O’Rorke (1901–74), New Zealand

born, had come to notice in placing joint third in the competition to design

the RIBA’s headquarters and gone on to build a reputation for designing

passenger-ship interiors. In 1946 he succeeded Edwin Lutyens as architect for

the National Theatre, for which his designs remained unbuilt. He took over as

architect for the new Club, leaving Murray, Delves, Murray & Atkins in

charge of maintaining the existing buildings. Wells, Cocking and Weston were

appointed consulting engineers, Ian Cocking in the lead. Commander A. E. Loder

(Secretary and Chief Steward) and Commander A. Westbury Preston were key

inside figures in seeing through the rebuilding project, as was Rear Admiral

Sir David Lambert as Chairman in the early 1950s.

Ambitions grew, with 6–10 Ensign Street to be acquired for demolition to

square off the site, and brief hopes that the Church Commissioners would

permit building above St Paul’s Vicarage. But costs kept rising with inflation

and a diminishing number of boarders gave rise to concern in 1949 that

expansion was no longer warranted. O’Rorke scaled down the plans by two

storeys, and a licence for the first phase was granted in 1950. A new problem

arose when the Merchant Navy Welfare Board was unable after all to contribute

funds. With a shortfall of £35,000 of an estimated £275,000, and costs still

rising, in 1951 O’Rorke suggested rebuilding the Dock Street range with the

taller central block to its rear for £160,000 to prevent further delay. This

was agreed and Charles Price Ltd (led by Kenneth Price) was given the contract

for the new building for £179,488 in March 1952. First Hardwick’s Ensign

Street block was re-modernised, to plans by Murray with R. Mansell as

contractor. A staircase was inserted in the northeast corner of the ground-

floor lounge, which was otherwise laid out with a billiard table and a

‘television set’. The Dock Street rebuilding ensued from 1954 and was

completed in 1957 for a final cost of £218,400. Even so, the central block had

also had to be abandoned, the new capacity was just 240 and there was a

deficit of £63,000.

O’Rorke’s building has six storeys and a setback attic, a steel frame and

reinforced-concrete floors, metal windows and copper roof covering. Above

curtain-wall glazing for the façade of the two lower storeys that housed

communal spaces, it is brown-brick clad. The flat-faced Modernism is

herbivorous yet stark. A lighter touch was introduced in the intertwined rope-

pattern ironwork of the first-floor balconettes. A lift motor-room tower

rising above the southeast staircase was a remnant of the centre-block plan.

There had been disagreements as to the relative size of cabins (still, after

all, so-called) for seamen and officers. The hierarchical view prevailed and

it was 1966 before washbasins were installed in each room. The former pub and

cartage depot to the north on Dock Street was demolished for yard access, and

8–10 Ensign Street came down in 1954 for a contractor’s site and then a car

park.

Following the closure of the London and St Katharine’s Docks in 1968–9 and

continuing financial difficulties the Red Ensign Club closed at the end of

1974. Hostel use was quickly re-established, the buildings being converted in

1976–8 for the Look Ahead Housing Association Ltd (Beacon Hostels), founded in

1973 by Mary Jones, a retired civil servant. The complex became a hostel for

single homeless men, with the London School of Nautical Cookery carrying on in

the basement. Christopher Beaver Associates were architects for the

conversion, Finchley Builders and then J. W. Falkner & Sons Ltd, carried

out the work in phases. Capacity at what came to be called the Aldgate Hostel

(sometimes Beacon House) shrank from 180 to 150 beds. Many of those housed

were construction workers and there was also use as a halfway house for men

released from prison. By 2012 Look Ahead had closed this and all its other

large ‘industrial-era’ hostels to shift to smaller specialist services.

Another conversion was carried out in 2012–14, the property having been

acquired by Michael Sherley-Dale, whose residential property company, JMS

Estates (IOM) Ltd, leased the premises to Wombat’s Hostels. This firm, founded

by Marcus Praschinger and Sascha Dimitriewicz with a name deriving from the

genesis of the business in their travels in Australia, had opened its first

youth or backpacker hostel in Vienna in 1999 and gradually expanded across

Europe. The refurbishment of the Dock Street–Ensign Street hostel was by

Andrew Mulroy architects, with Eastern Corporation as the main contractors,

and Peter Thompson as the project manager. In a light-touch approach, little

external fabric apart from the entrance doors and canopy was replaced. The

middle range of the 1860s was raised by two storeys and its long-since disused

staircase was removed. The main internal change was from single bedrooms to

dormitories. Wombat's London opened with 618 beds. The vaulted cellar was made

a café and bar with exposed brickwork, and the internal courtyard was

landscaped as a garden. In 2015 the access road to the north was infilled with

a three-storey extension using Moleanos (Portuguese) limestone cladding for

the façade. An additional attic bedroom storey on the Ensign Street building

was formed in 2018–19, with a two-storey addition to the infill block set to

follow on, all designed and overseen by Mulroy and Thompson with Eastern

Corporation.