Early history of the site of the 1901 Gallery building

Contributed by Survey of London on July 10, 2018

The Whitechapel Gallery has since 2009 consisted of two buildings, the

original gallery, opened in 1901, on the site of 80A, 81 and 82 High Street,

and the former Passmore Edwards Library, built in 1891–2 on the site of Nos

77–80.

To the east, the former library occupies the site of four 12ft-frontage

timber-framed shophouses, there by 1638 when Eleanor Ireland, a Westminster

widow, took them on a lease from the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral.

The houses and their ‘little garden plots’ were then in the occupations of a

weaver, a translator (a cobbler), a collarmaker and a scrivener. By 1818 they

were in single ownership and all had been refronted in brick by 1884.

Nineteenth-century use was typical of the High Street. No. 77 housed a

gingerbread maker then a ‘commercial coffee house’ from around 1855. No. 78

was a gentleman’s outfitters in 1825 when it sported an ‘excellent bow-fronted

shop’; later occupants included a haberdasher, a staymaker and, from around

1855, Godwin Rattler Simpson, patent window-blind maker. No. 79 was a

draper’s, latterly Robert Rycroft who moved to No. 75 upon demolition in 1890.

No. 80 was a jeweller’s and watchmaker’s for twenty years prior to

demolition.

A substantial brick storehouse to the rear was part of the Swan brewery, as

was most of the site of the original Whitechapel Gallery. The large inn, the

Swan with Two Necks (later the White Swan), already described as divided into

two in 1616 and possibly already present in the early fifteenth century, later

became 81 and 82 Whitechapel High Street. These gable-fronted, timber-framed

buildings survived in large part until 1897 when they were demolished to make

way for the gallery. They appear to have been erected by Richard Loton in the

1650s, when farthing trade tokens marked with a swan and ‘RL’ were issued.

Samuel Cranmer’s son, Caesar (later Sir Caesar, 1634–1707), and his second

wife’s second husband, Henry Chester, sold the Swan property in 1656 for

£2,360 to Loton. He was a clothworker turned brewer, locally eminent as an

Independent, lay preacher and Parliamentarian, and a member of the Tower

Hamlets Committee of Militia.

The larger eastern half (No. 81) was substantial, with eleven hearths in 1666

when Abraham Anselme (or Ansell), who also then held a lease of the brewery,

was in occupation. Anselme (d. 1678) had grown wealthy as a Hearth Tax

commissioner and, like Loton, with whom he was associated, was a well-

connected Parliamentarian. Loton died in 1692 and his son, Edward Loton, sold

the inn and associated property in 1695, when the occupying brewers were

Edmund Paris and Thomas Sparrow. The purchaser was John Pettit, a citizen

Merchant Taylor. George Crane took occupancy, then in 1701 Pettit gave a

31-year lease of the inn (No. 81) to Thomas Edwards, a brewer. Tenancy of the

‘victual house or taphouse’ (No. 82) went to John Heard, a victualler.

Only a degree smaller, No. 82 was similar to No. 81, but had or came to have a

canted oriel to its first and second floors. From the 1820s it was mostly

occupied by clock and watchmakers, with interludes as a hat dealer’s and a

tobacconist.

Samuel Pedley, of a family of Whitechapel cordwainers, acquired the freehold

of both properties by 1847. No. 81 saw varied later usage, mainly by

auctioneers from the 1830s to the 1860s. In 1849 a petition was raised against

an application from a tenant, Thomas Harwood, who sought a music and dancing

licence for his ‘Hall of Science’, which he claimed had been ‘long used for

Literary and Scientific Purposes which tended greatly to the mental

improvement of the Working Classes’, but which the petitioners alleged was ‘a

great nuisance to the respectable tradesmen living in the neighbourhood’, and

that Harwood had ‘for a long time carried or permitted music and dancing and

other entertainments … and has allowed prostitutes and persons of the worst

character to assemble therein’. The building’s extensive upper parts were

used briefly in the mid-1850s by the East London Ragged School Shoeblack

Society as a refuge for twenty-one homeless boys, who were housed, clothed,

fed and taught skills such as tailoring and shoe-blacking. For the last thirty

years or so of its existence, No. 81 housed a photographer’s studio, where

William Hobbs (1837–93) was succeeded in 1887 by William Wright. Upper rooms

were otherwise variously occupied by households that included tailors and a

music publisher.

By the mid-nineteenth century the alley from the High Street to what had been

the brewery in Swan Yard had become Queen’s Place, which swiftly became a foul

court. Entry, about 3ft wide, was through No. 81. In 1860 Queen’s Place

attracted the unfavourable attention of the Whitechapel District Board of

Works, and thence the Metropolitan Board of Works, for two recently erected

three-storey west-side tenements, each about 15ft by 20ft, lit only by a

narrow gap between them and the infants’ school in Angel Alley, and the 6ft-

wide court itself. They had been put up on the site of a warehouse, as,

according to the Whitechapel Board’s indefatigable Medical Officer of Health,

John Liddle, a recent slew of warehouse building on Commercial Street on the

site of poor housing had shifted local needs to housing. By 1881 there were

forty-eight people living in the court’s four small houses.

No 80A was demolished along with Nos 77–80 in 1891. A single-storey shop was

erected on the site in 1893 for R. W. Dermott, the watchmaker dispossessed

from No. 80, only for it to be sold with Nos 81–82 for the gallery in 1896.

Whitechapel Gallery: pre-history and early history up to 1914

Contributed by Survey of London on July 5, 2016

Although it opened in 1901, the Whitechapel Gallery can date its effective

foundation to 1881 when Samuel Barnett began an annual picture exhibition in

three rooms at the St Jude’s schools behind St Jude’s church in Commercial

Street. The exhibitions themselves grew, before the founding of Toynbee Hall,

out of the Barnetts’ wider educational mission, more particularly the

inspiration that art could bring in ‘the paralysing and degrading sights of

our streets’ in Whitechapel. The Barnetts had often conducted rather awkward

parties where their impoverished neighbours could see ‘interesting and

beautiful things’ in the drawing room of the vicarage.

Despite the rather dimly lit rooms, hemmed in by other buildings, the

exhibition attracted 10,000 visitors. It included one room entirely filled

with items from the South Kensington Museum, paintings lent by artists and

collectors, including work by G.F. Watts and John Brett, middle eastern and

western ceramics, including Staffordshire, Wedgwood and contemporary work by

De Morgan and others, and art-needlework and Morris & Co other textiles.

Costs were low with catalogues a penny and several days with free entry. By

1886, visitors had reached 46,000, and three rooms were added to the school to

expand the shows.

Barnett’s first idea for a site for the new gallery was the Baptist Chapel

opposite St Jude’s. It was a convenient and spacious site, and had the

potential, like the chapel building itself, for natural lighting on three

sides. On several occasions over three years between 1893 and 1896, Barnett’s

friend, Dr John Clifford, pastor of Westbourne Park chapel, approached the

chapel's pastor on the Barnetts’ behalf. The pastor’s initial response in June

1893 was that he did not think the church ‘would be in the least disposed to

sell’ the building. Despite this discouragement, by the following month a

draft scheme for a charitable trust had been prepared and by February 1894

Barnett had come up with an ambitious proposal for a large building combining

picture gallery, art school and accommodation for the Whitechapel District

Board. The Board had met in inadequate accommodation in Little Alie Street

since its inception in 1888 and in 1890-1 a special committee had assessed

costs and plans of various other local town halls as models.

In March 1894 the architect Charles Harrison Townsend had produced a grand

outline scheme for the site. Townsend was a long-term associate of the

Barnetts, whom he had met at a party in 1877, the year that his sister Pauline

began her 22 years of work for the Barnetts, setting up a Whitechapel branch

of the Society for Befriending Young Servants. He had also been on the

committee that organised the St Jude’s picture exhibitions since they began.

He was then working on the Bishopsgate Institute for the educational reformer

Revd William Rogers, with public library, hall and meeting rooms, and would

soon be building the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill.

As well as the chapel, the scheme was to occupy the sites of seven houses to

the rear in New Castle Place, ‘by its nature not likely to be expensive’. The

building, known only from a letter to Barnett, would house not only a top-lit

gallery, accessed by a wide staircase and lift, on the second floor, but an

art school (on the first floor), 19 ‘vestry offices’ (in fact, offices for the

Whitechapel District Board of Works) and a boardroom to seat 64 (on lower

ground and first floors) and a vestry hall to seat 755 on the raised ground

floor. An additional house in New Castle Place could be adapted as a

caretaker’s house. Townsend estimated the cost of this building at a highly

optimistic £8,000 to £10,000.

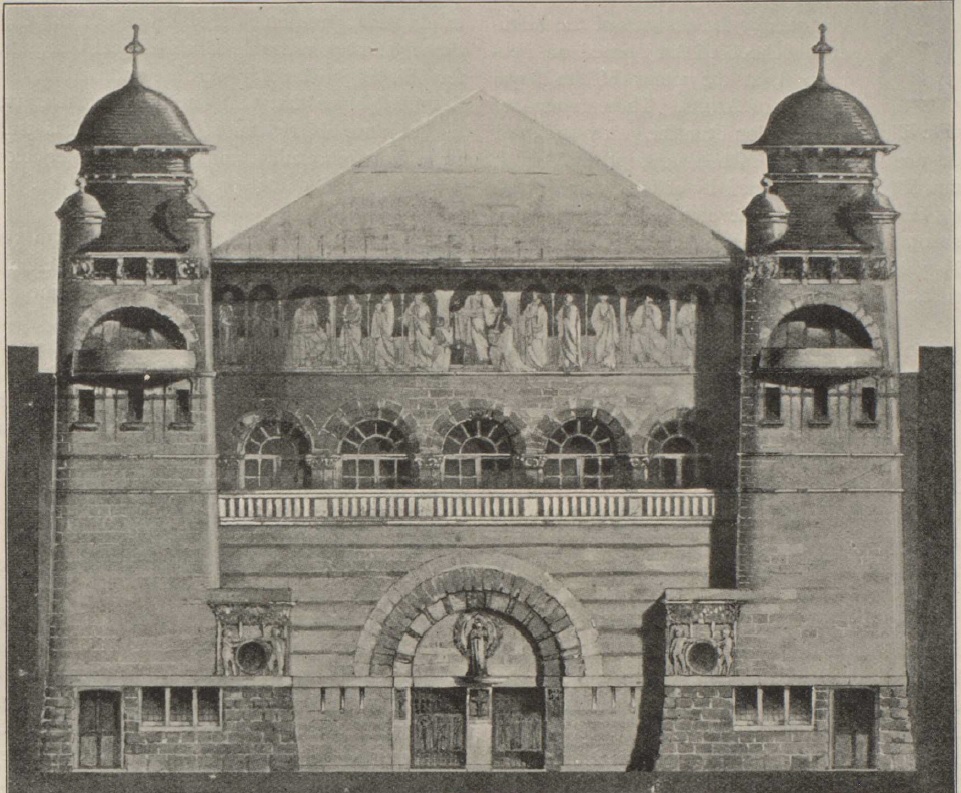

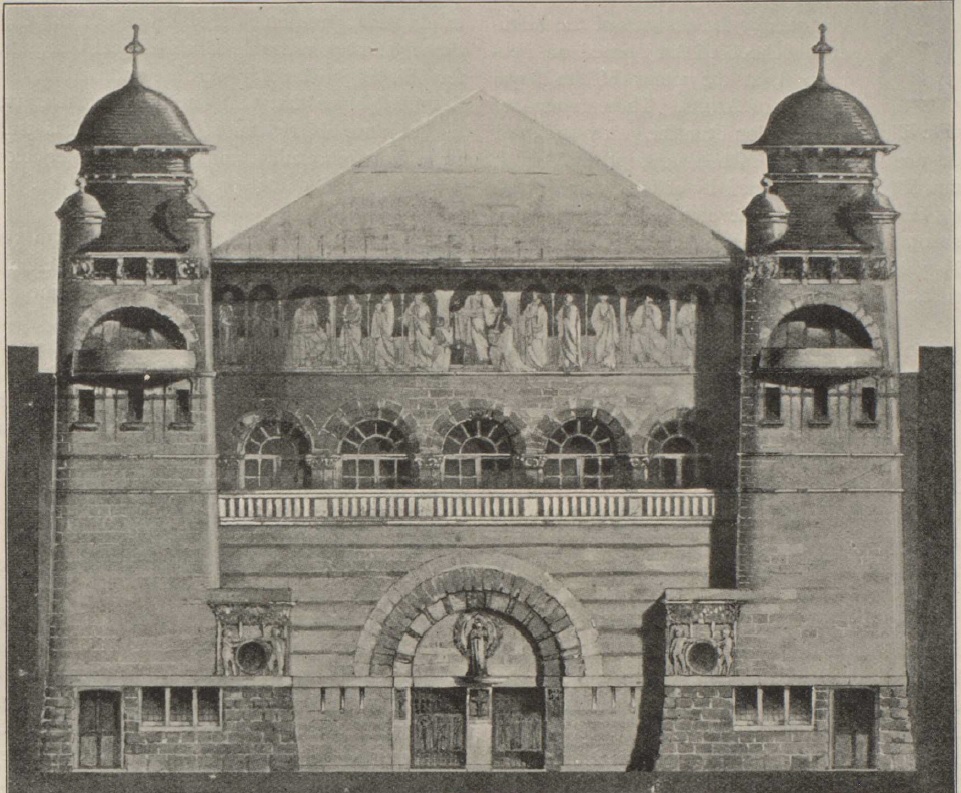

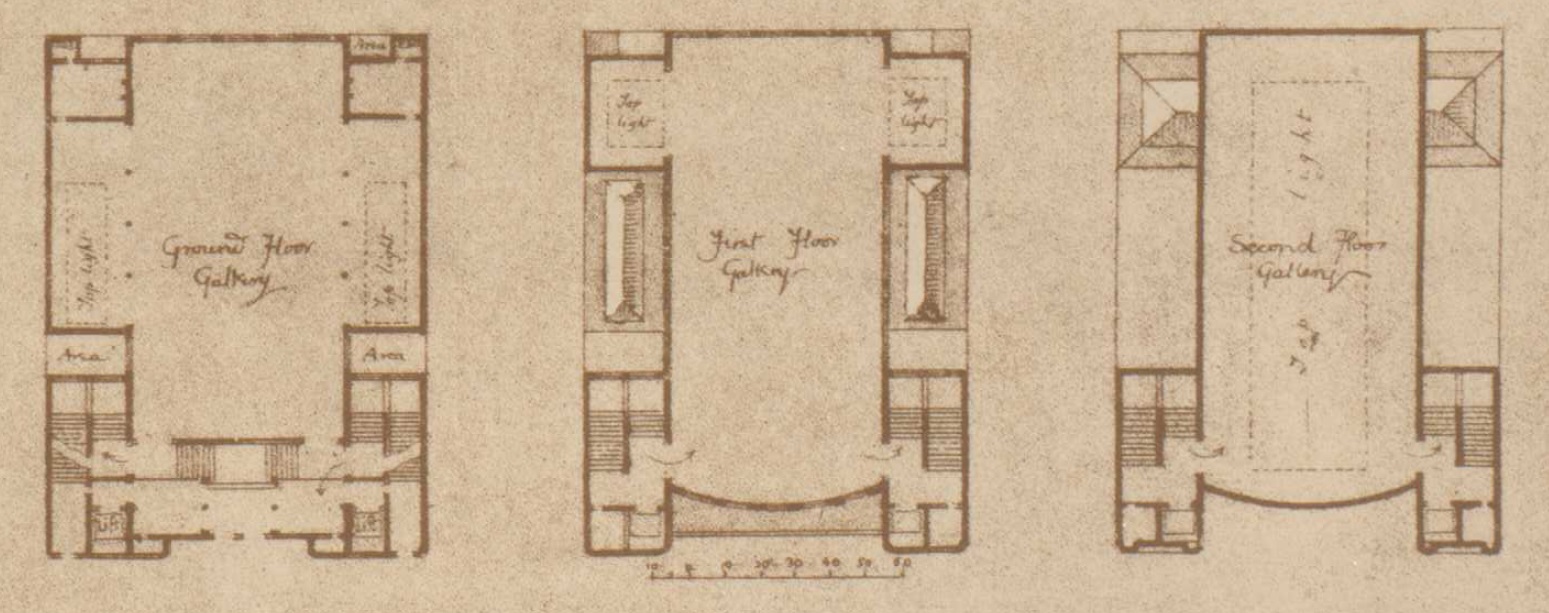

Charles Harrison Townsend, elevation of first design for Whitechapel Art

Gallery, 1896 (from The Studio, 10 [1897], p. 131)

In the summer of 1896 Townsend exhibited a front elevation of the picture

gallery at the Royal Academy. It was radically original, a symmetrical

frontage in warm yellow flanked by square towers topped by ogee-capped

cylindrical final stages. Between the towers the upper half of the frontage

was set back and convex, its upper half entirely filled with a 65ft-long

mosaic by Walter Crane of classical figures, probably the Muses, set against

an arcade, the lower half a real arcade of five semi-circular windows. These

sat behind a straight balustrade topping the lower half of the frontage,

striped in grey-green Cipolino marble, above a pair of doors set under a giant

semicircular arch of reddish-yellow and white marble. Two years earlier

Townsend’s art critic brother Horace had visited the radical American

architect H. H. Richardson and had reported on this in the Magazine of Art

in 1894. Harrison Townsend’s design, especially the rugged stonework of the

battered ground level and the repeated bold semicircular arches, was one of

the first expressions in the UK of Richardson’s influence.

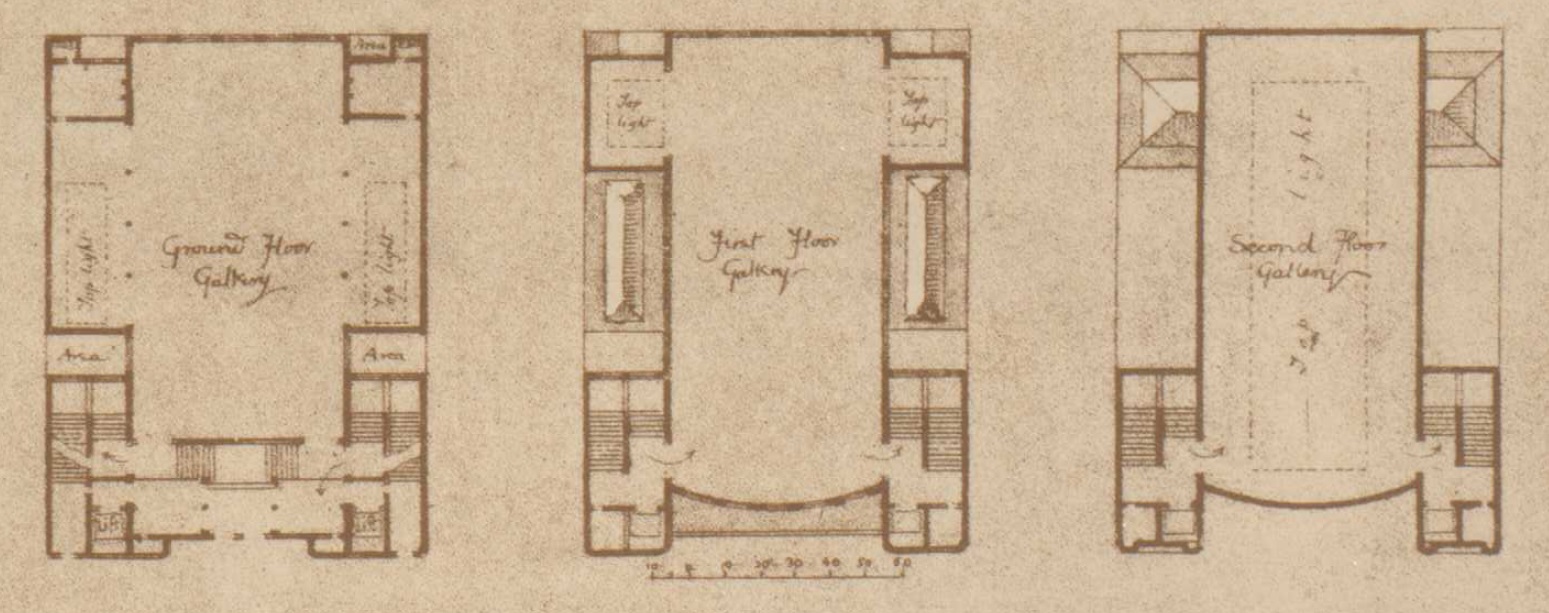

Charles Harrison Townsend, plans of first design for Whitechapel Art Gallery,

1896 (from The Builder, 30 May, 1896)

Although by the time it was exhibited in the summer of 1896 it was described

merely as a design for the new picture gallery, the vast scale – it was around

110ft wide – can only mean it was designed for the site of the Baptist chapel

and schools, that is the width of the seven houses in New Castle Place to the

west that Townsend had mentioned to Barnett. It was evidently the site Barnett

favoured, though Harrison’s design was more an aspiration than a serious

suggestion for a building costing less than £10,000.

Barnett had apparently abandoned the idea of including the Board of Works hall

and offices in his scheme, after a final approach to the Board in 1895.

The realities of financing the gallery were making themselves felt, more

particularly the views of a significant potential benefactor. In 1894 the

painter G.F. Watts, a long-term supporter of Barnett’s Toynbee exhibitions,

had raised the possibility of a major donation for the new Whitechapel gallery

with the Cornish philanthropist John Passmore Edwards, who had paid for the

library and lecture hall at the South London Gallery. Edwards was a generous

but controlling philanthropist, a position that was to dog the Whitechapel

Gallery.

‘Your idea of municipal buildings, picture gallery etc for Whitechapel is too

capacious and composite for me,’ he told Barnett. ‘What Mr Watts and I talked

over was a very different thing, and was merely a picture gallery as an

addition to Toynbee Hall, as the Lecture Hall and Library I paid for at

Camberwell … was an addition to the South London Fine Art Gallery.’ Most

tellingly he added ‘I am surprisingly egotistic to do a thing in this way

wholly or not at all. I can’t carry out your big scheme and must confine my

attention to smaller ones.’

Until the summer of 1896 Barnett was still pursuing both the idea of an art

school and the Baptist chapel site. He took soundings both on the advisability

of including some kind of art school, perhaps in response to the closure of

C.R. Ashbee’s Guild and School of Handicraft at Essex House in Mile End Road

the previous year. The consensus was that the proximity of the nascent Cass

Institute and the Whitechapel Craft school (for training elementary teachers)

made another art school superfluous : ‘If the Cass Inst. has an art school

there will hardly be room for another so near and there is no local clientele

to draw on for such a school… You would probably find that those who used the

gallery were by no means the same people as came to the school, and that the

latter came from a distance. Another suggestion was that some kind of

joint enterprise might be possible. At the same time Dr John Clifford

continued to press for the Baptist Chapel site on Barnett’s behalf.

Passmore Edwards, however, was not keen on the art school idea, and also

favoured a site on Whitechapel High Street, adjoining the Free Library for

whose building he had paid in 1891-2. This consisted of 80a, 81 and 82

Whitechapel High Street. One of the gallery’s other benefactors, the banker

Samuel Montagu, Baron Swaythling, reported to Barnett that ‘your architect is

not sweet on the site’, which had a frontage of only 50ft, which included

shops and the west side of the notorious slum Queen’s Place,.and referred to

the ‘difficulties of Mr Passmore Edwards’ selection of that particular site’,

one being the ‘high’ price. Originally only about a depth of 80ft had been

considered but Townsend could not fit in a usable building (the Guildhall

Picture Gallery at 5000sq ft was the model suggested by Barnett), More land

was added which extended about 130ft to Warner’s Osborn Street iron foundry to

the rear. The site enjoyed a High Street frontage, including the four shops,

and the cost was £6000. However, the offer of £5,000 by Edwards to pay for the

building itself was enough to decide the matter in the site’s favour. Townsend

had begun considering the possibilities of the High Street site in May 1896,

when he had already come up with the basic eventual components of two nave-

like galleries one above the other, the lower wider to allow strips of

rooflights at the edges. Townsend politely quashed Barnett’s notion of a

further gallery beneath: ‘As this is a basement room I hardly see how to

arrange this.’

There followed an exhausting two years for Barnett while he clawed together

the funds for the site, all the while mollifying the demanding Passmore

Edwards, and the over-optimistic Townsend who admitted in February 1898 that

his building was likely to cost £7000. William Blyth, secretary to the

trustees, went to see Passmore Edwards who ‘thinks Townsend a very expensive

architect & one who places too much importance upon artistic effect’. He

told Blyth he thought ‘his’ architect, Maurice B. Adams, editor of the

Building News, which Passmore Edwards owned, and designer of the St George

in the East Free Library in Cable Street, for which Passmore Edwards had paid,

could have put up a suitable building for £5000.

A further and trickier problem soon arose when Passmore Edwards made it plain

that though he had offered a further £1200 it was dependent on the gallery

being named the Passmore Edwards Gallery. Townsend tried manfully to squeeze

the name Passmore Edwards Picture Gallery, ‘the Passmore Edwards… in a smaller

font… [so as not to] make it the every eye and centre of the building as he

wants’, on to the frontage, as he knew a lot of money depended on it.

Townsend later told Barnett that Passmore Edwards had offered to make him the

architect of a building he was about to ‘present’ if Townsend succeeded in

having the gallery named after him. As a sop, Barnett succeeded in getting the

neighbouring Free Library renamed the Passmore Edwards Library, but was

adamant that ‘Neither by word, or by letter have you asked or have I given a

promise about the name of the gallery’, expressing ‘regret that you cared to

blot with a name charity so noble as yours’, later apologising to the

sensitive Passmore Edwards for the word ‘blot’. Passmore Edwards was

equally assertive about his ‘little weakness’ and withdrew the offer of the

extra funds.

The issue for Barnett was his incomprehension about personal vanity, which he

lacked, and of fairness to the many other donors. His prominence as a social

reformer meant these were varied in source and amount. Caroline Turner,

Headmistress of the High School for Girls, Exeter, wrote to Barnett with a

small subscription in October 1897: ‘During the Spring Term of this year, I

gave some Literature Lessons to the elder girls on William Morris and his

hopes and efforts for happier lives for the people. Soon after we saw a notice

of your wish to get a permanent Picture Gallery for the East End, and the

enclosed cheque represents a few subscriptions from those of my Literature

Class who were able and willing to help.’ John Bullock, a Toynbee Hall

resident, sent £5, which ‘he was ashamed to be enclosing’. But the bulk of the

money came, directly or through their contacts, from the Anglo-Jewish

community of City financiers with a long-standing interest in Barnett’s

Whitechapel work. Samuel Montagu, who had offered £100 reward to help catch

Jack the Ripper (because the murders had led to an upsurge in anti-Semitic

attacks), gave £1000 and suggested finding another five similarly inclined

donors. Chief among these was Barnett’s friend and fellow trustee, Edgar

Speyer, future supporter of the Proms and the developer of the Tube network,

who secured £700 from Schroeders, Hambros, Werhner Beit & Co. and L.

Messel, and who gave more than £2,500 himself when the amount raised fell

short. Other major donors were the shipbuilder A.F. Yarrow, whose firm

was based on the Isle of Dogs, and the Cornish landowner, horticulturist and

secret philanthropist J.C. Williams of Caerhays Castle, who gave £1000 on

condition of anonymity. Fundraising in 1897 had not been made easier by

demands made on the charitable purse by two major campaigns that year for

Indian famine relief and the Prince of Wales Hospital fund. Speyer also found

that ‘the scheme is one that does not appeal to everybody’.

Whitechapel Art Gallery was established as a charity, its constitution

finalised by the early 1899. Its trustee body and stated aims reflected the

Barnetts’ 25-year mission to educate their parishioners and provide the

spiritual balm of art. Trustees included among its co-opted Trustees,

Henrietta Barnett and their long-term benefactor Speyer, and representatives

of, inter alia, the neighbouring Free Library, the London Parochial charities,

the Royal Academy, of Toynbee Hall and the Technical Education Board of the

LCC. Its aims were to mount free loan exhibitions of ‘high-class modern

pictures’, or those illustrating history, art and industry, and work by local

people including schoolchildren.

Building work had commenced in November 1898 and was completed a year later,

despite Passmore Edwards withdrawing £1200 of his offered £7200 when Barnett

stood firm on naming the gallery after him. A.F. Yarrow, the shipbuilder donor

made up half the shortfall with the observation that ‘This seems to me a very

funny sort of demand [the name of the gallery], as his name is pretty well

scattered all over England.’ The builder was John Outhwaite & Son of East

Smithfield, a some-time Whitechapel District Board member.

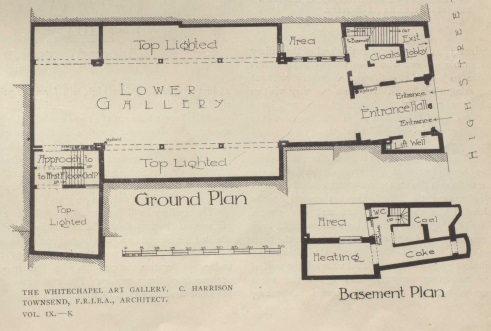

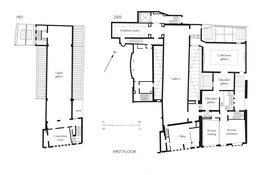

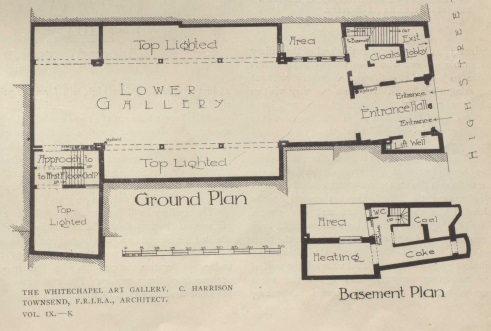

Basement and ground plan of the Whitechapel Gallery as built, from the

Architectural Review, 9 (May 1901), p. 129

The gallery’s plan was limited by the narrow deep site, slightly offset

because of the ancient, meandering building line to the High Street. The

squarish entrance hall was flanked by a small space intended for a lift and a

square staircase hall to the right leading to the first and second floors. The

entrance hall led through to a 100ft x 50ft lower gallery, a spare nave-like

room its trabeated ceiling set between higher pitched glazed roofed aisles,

its south end lit by a light well created against the neighbouring library. At

the north west end of the main gallery was a smaller top-lit gallery separated

from it by another staircase.

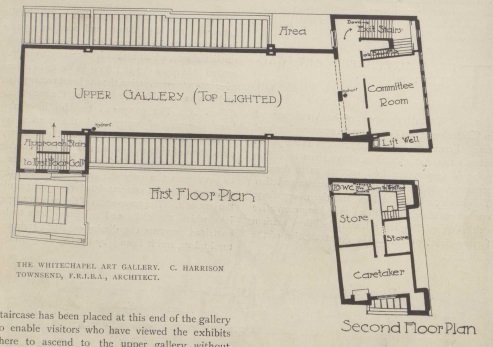

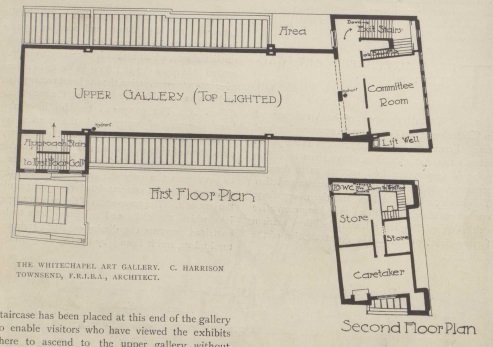

First- and second-floor plans of the Whitechapel Gallery as built, from the

Architectural Review, 9 (May 1901), p. 130

The main stairs at the front led up to narrow first-floor gallery sitting over

the central part of the lower gallery, with an exposed curved-brace top-lit

roof. Over the entrance hall was a committee room across the front of the

building, with store- and caretaker’s room above.

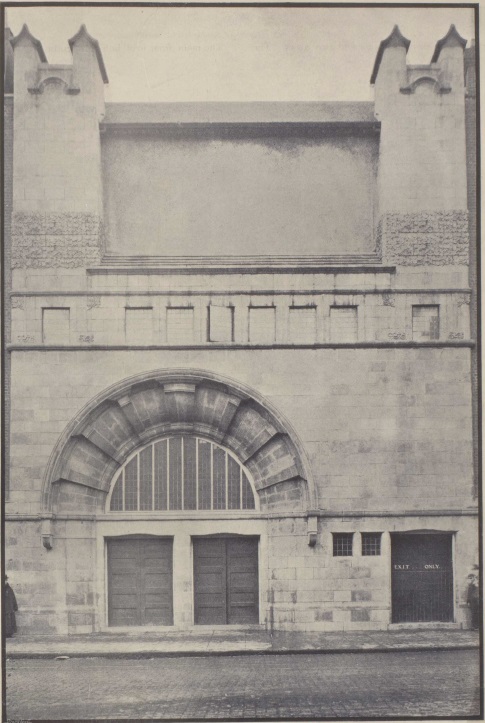

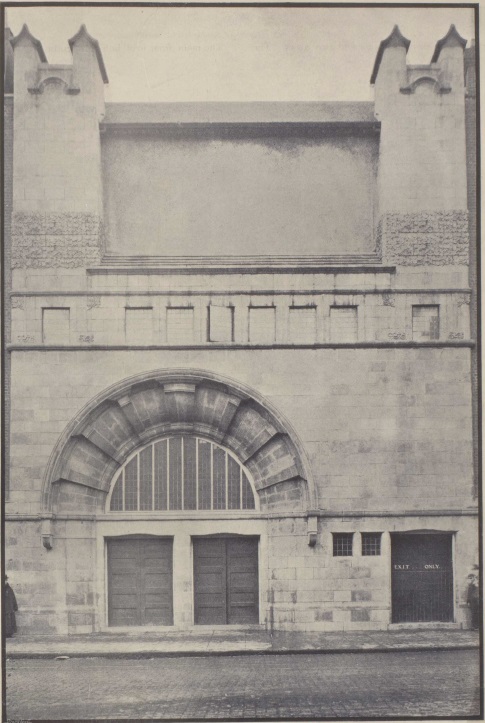

Photograph of tthe Whitechapel Gallery, 1901, from the Architectural Review,

9 (May 1901), p. 131

The frontage to Whitechapel in an austere 1890s free-style, is arresting, a

simplified, sleeker version of Townsend’s Baptist Chapel site design. It is

dominated by a giant semicircular arch over twin entrance doors,

asymmetrically set beneath a strip of simple square windows lighting the first

floor. The second floor rooms were originally lit only from the side and rear

to allow for a giant panel set between tapering square towers, each topped by

four small steeply gabled roofs, but not the caps Townsend hoped to add. This

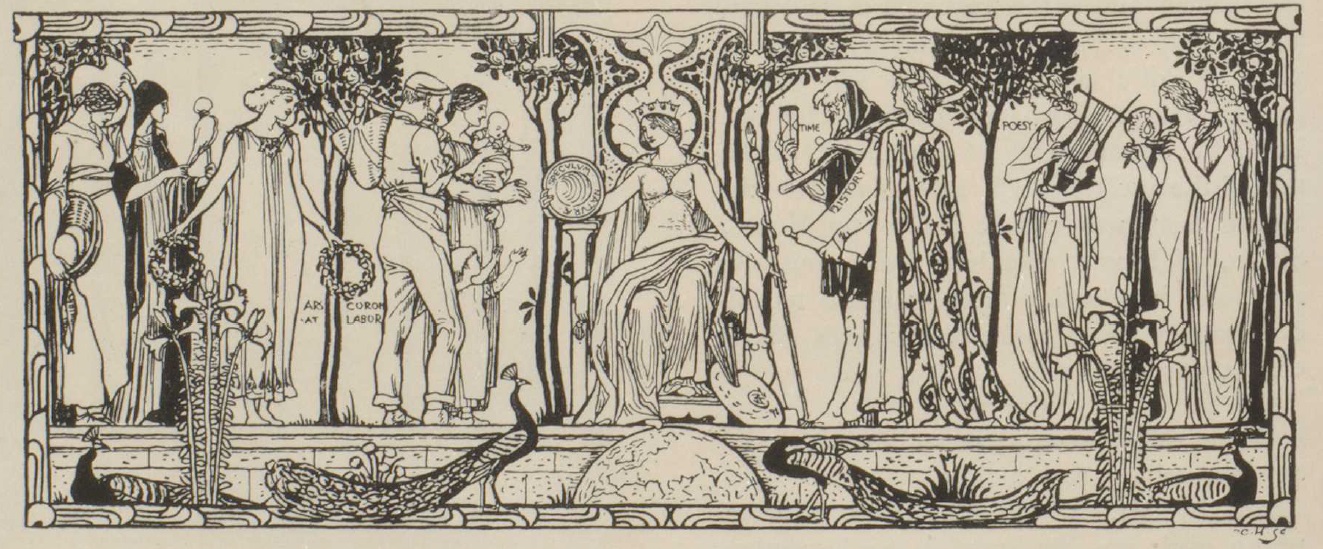

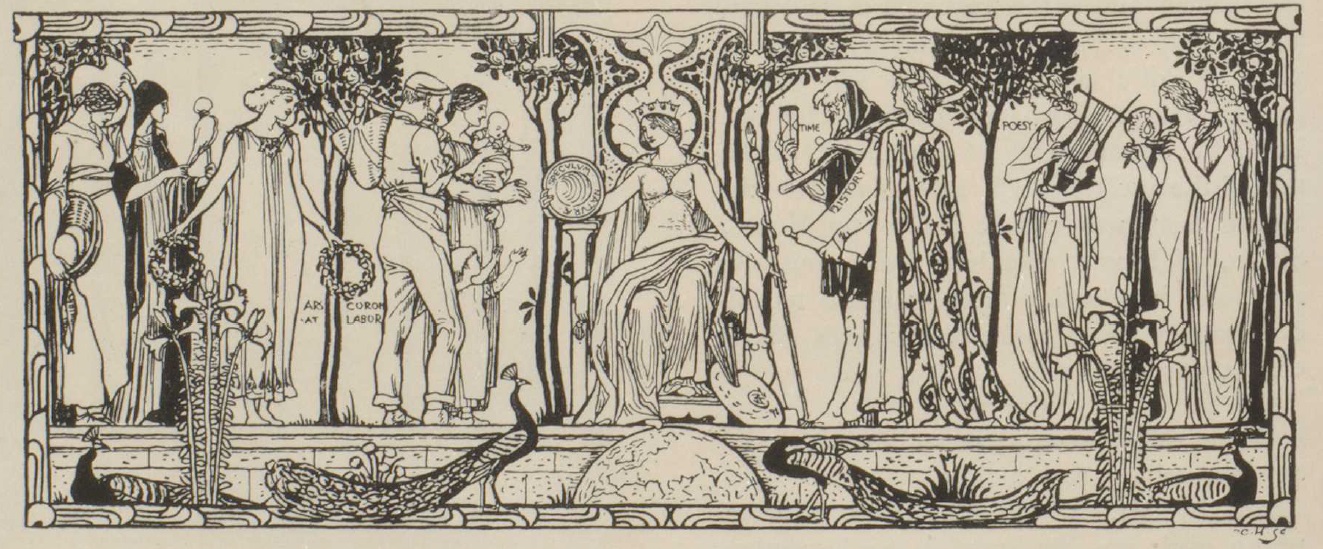

panel was intended for a mosaic, The Sphere and Message of Art by Walter

Crane, in a sinuous fin-de-siècle manner, adorned with peacocks and lilies.

Figures of Poesy, Truth, History etc pay homage to a seated figure of Art,

gazing into her speculum naturae.

Walter Crane's unexecuted design for a mosaic panel

The money to pay for its execution was never forthcoming. The frontage was

uniformly clad in buff terracotta tiles by Gibbs & Canning of Tamworth,

the only decoration bracket voussoirs to the deep entrance arch, string

courses and shallow-relief moulded trees in an art nouveau manner to the bases

of the towers, and gilded Whitechapel Art Gallery lettering carved above the

twin entrance doors by Daymond & Sons.

The walls were lined in red-dyed linen, from Liberty, with a framework of

battens from which to hang pictures, with a similar treatment to the moveable

wooden screens to augment the hanging space.

Ideas for a frieze in the entrance hall by Gerald Moira, then working on the

frieze in the Bechstein (later Wigmore) Hall also came to nothing.

Thrift determined the interior fittings – kamptulicon rubberised matting in

the board room, coconut matting and woodblock in the galleries, a plain mosaic

floor in the entrance vestibule.

The gallery was opened by Lord Rosebery, on 12 March 1901, twenty years after

he opened the first of Barnett’s Whitechapel exhibitions. By then Charles

Aitken, a former schoolmaster, had been appointed director. He had experience

lecturing on art at the Regent Street Polytechnic and the Social and Political

Education League, and sported references from Charles Holroyd, director of the

Tate Gallery, and Walter Crane, who described him as ‘a friend of ours… I

believe he is a well-informed and cultivated man and would be well qualified

for such a post.’ At the end of the first year Barnett noted with

satisfaction that the Trustees’ ‘aim has been to open to the people of East

London a larger world than that in which they usually work, to draw them to a

pleasure recreating to their minds, and to stir in them a human

curiosity….[they] came in greater numbers than expected, they came both to

enjoy and to question, they bought catalogues by the thousand, the attended

lectures and they welcomed guidance.’

In the first decade Aitken implemented the Trustees’ stated policies,

continuing the St Jude’s schools’ Easter exhibitions, augmented with two or

sometimes three themed exhibitions a year. The spring exhibitions, usually a

mixture of living artists (works often lent by the artists, or by

philanthropic-minded collectors) and old masters (Reynolds, Gainsborough,

Romney, Constable, Turner), lent by the national galleries, regularly

attracted more than 200,000 visitors. The exhibitions were free, as decreed by

the Trust deed, and catalogues cost a penny. Among the themed exhibitions in

the first decade were shows on Chinese art and Japanese art, and a pioneering

exhibition in 1906 of ‘Jewish Art and Antiquities’, accompanied by lectures by

Hermann Adler, the Chief Rabbi. The displays were (typically for the

period) crowded, the mission still overtly pedagogic. Of the Chinese

exhibition in 1901, Barnett wrote:

‘Objects [were] arranged so as to illustrate the life of the Chinese people…

bays of the Gallery transformed into a temple, a shop a rich man’s sitting

room and bed-room and a poor man’s room…. ‘The result of the interest was,

probably, a more vivid conception of the common humanity of the people's

underlying habits so unlike those familiar at home – an increase, therefore,

of good will.’

The focus was not exclusively fine and decorative art: early exhibitions

included one about shipping, complete with detailed ship models. Aitken

also set the exhibitions within a wider programme of cultural and educational

enlightenment within the gallery, with regular lantern lectures, and concerts

by the Ladies’ Aeolian Orchestra.

The upper gallery from the beginning was the focus for displaying the work of

local schools, and not exclusively art work, but also ‘excellent displays of

gym drill, singing, reciting, first aid and dressmaking.’ A library of

prints and photographs of works of art was open to children to borrow, a

facility Henrietta Barnett thought ‘quite as important as lending books’.

Regular guided school visits were arranged, and Barnett noted with

satisfaction in 1903 that it was a ‘common sight on a Sunday a child acting as

guide to the family party’.

Barnett maintained his faith in the exhibitions as a universal social

palliative: ‘A greater love of beauty means, for instance, greater care for

cleanliness, a better choice of pleasures, and increased self-respect. The use

of the powers of admiration reveals new interests which are not satisfied in a

public house, but drives their possessors to do something both in their work

and their play which adds to the joy of the earth. The sordid character of

many national pleasures and the low artistic value of much of the national

produce is due to the unused powers of admiration.’

A first inkling of the Whitechapel’s engagement with the avant garde came in

1907 when members of the New English Art Club (though by then not quite the

pioneers they had been when founded in 1886) were included in the Spring

exhibition, with the more traditional popular exhibition to be held in the

autumn. Much more overtly challenging were Twenty Years of British Art

(1890-1910) held in 1910 and Twentieth Century Art: A Review, organised by

Aitken, whose efforts at Whitechapel had secured him the directorship of the

Tate Gallery, and his successor at Whitechapel, Gilbert Ramsey. Barnett had

remained chairman of Trustees till his death in 1913, but Henrietta Barnett

was made uneasy by the 1914 show, asking Ramsey ‘not to get too many examples

of the extreme thought of this century, for we must never forget that the

Whitechapel Gallery is intended for the Whitechapel people, who have to be

delicately led and will not understand the Post-Impressionists’ or the

Futurists’ methods of seeing and representing things’.

Whitechapel Gallery since 1914

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 25, 2017

The Gallery in war and peace, 1914-39

The shows were emblematic of an attempt to shift away from the over-arching

pedagogic tone and paternalistic governance of the early years. After the

First World War which claimed the lives of Gilbert Ramsay and his successor,

Samuel Theed, though, the gallery was to be hampered on and off for more than

50 years by financial difficulties. As early as 1904 Barnett had succeeded in

interesting the LCC in taking it over, a proposal that failed only when it

became clear that in ceasing to be a charity, the gallery would lose £1000 a

year of its funding from the London Parochial Charities and others. Instead, a

grant from the LCC of £350 a year was agreed in 1908, for which the LCC was

granted use of the upper gallery for exams and exhibitions illustrative of

educational work three months of the year. This grant had been reduced to

£250 by 1916, when the war curtailed the LCC’s work, and was discontinued

entirely in 1922. The loss of this and the low ebb of donations meant

that with an income under £1000 a year closure, at least for part of the year,

was a possibility, though the London Parochial Foundation stepped in with an

extra £500 in 1923, and the secretary/curator, J.N. Duddington, continued in a

hand-to-mouth fashion throughout the 1920s, 30s and 40s, scraping together

donations and bequests to sustain three exhibitions a year.

The financial precariousness of the Gallery meant few changes to its structure

beyond maintenance and decoration for many years. In 1918 two murals either

side of the entrance hall by Elsie McNaught were created as a memorial to

Samuel Barnett. In 1924 the lower galleries ‘which had become very

depressing in appearance’, were whitewashed and the walls matchboarded and

painted with cream Sanotex ‘which gives a good background to all works of

art’.

A notable event in the 1930s, a decade when shows were aimed principally at a

local audience once again, was the display in January 1939, in the final

months of the Spanish Civil War, of Picasso’s Guernica, which attracted a

large audience and raised funds for ‘Aid Spain’.

A shift in direction, 1945-76

During the war the building had been requisitioned by the Ministry of Works

and the roof sustained some damage, repaired after the war by grant from the

newly founded Arts Council of Great Britain. The following 30 years saw a

renewed negotiation between the needs of the gallery as a local resource in a

period of constantly changing Whitechapel demographic and successive

directors’ desire to develop an adventurous exhibitions’ programme. An

editorial in the Burlington Magazine in 1951, ‘the Whitechapel Gallery can no

longer draw the same crowds, nor serve quite the same purpose as before. In

1900 the East End had little in the way of entertainment except public houses,

whereas now the Gallery has to compete with film, the wireless, television,

football pools and greyhound racing….to-day residents of Whitechapel tend to

travel to the West End for entertainment.’ Visitor numbers had fallen to

less than 13,000 a year by the time Hugh Scrutton was appointed director in

1947 but he succeeded, with renewed grant aid from the LCC, the local East

London boroughs, the newly founded Arts Council, and private donations in

raising this to 41,000 by 1953. The year before a new young Director, Bryan

Robertson had been appointed and radically shifted the gallery’s focus in his

17-year tenure from the parochial to the international with a series of what

would now be called blockbusters of contemporary art, including, one-person

shows of Mark Rothko, Bridget Riley and Jackson Pollock, as well as This is

Tomorrow in 1956, a collaboration between artists, sculptors and architects

often cited as the founding of Pop Art in Britain as it included Richard

Hamilton’s collage Just What is it That Makes Today’s Homes so Different, So

Appealing?

From 1949 to 1970 the upper gallery was rented by the LCC London Education

Services (then, from the LCC’s demise in 1965, by the Inner London Education

Authority) for exhibitions aimed at school parties (‘The Artist in the

Theatre’, ‘A creative approach to printmaking’) and for classes in

printmaking, pottery, etc. But while these shows raised the gallery’s

profile and visitor numbers, it did not connect with the local authorities,

who cut their grants. Mark Glazebrook, Robertson’s successor in 1968, cemented

this change in direction by taking back into gallery use in 1970 the upper

gallery. He felt that the distinction between ‘education’ and ‘non-

educational’ art was undesirable, and saw the upper gallery as ‘potentially

one of the most desirable galleries in London. Cleared of its present screens

and cubicles, so that one could see the architectural shell, and rejoined to

the Lower Gallery, it would add up to being by far the finest set of galleries

in London for certain exhibitions…. [and] could put the Whitechapel “back in

business”’.

Glazebrook resigned in 1971, and there followed a difficult period when the

gallery was dependent on a reluctant GLC (its Conservative Leader, Desmond

Plummer, had observed in 1970 ‘I very much doubt the value of this Art Gallery

and am dubious of its management’), the Arts Council and private donations via

the Whitechapel Gallery Society had fallen to £68.

Whitechapel Gallery First extension, 1984-5

By the mid 1970s the Whitechapel Gallery was in poor condition: ‘The problem

here is mostly one of maintenance. It is a strongly built building but

expensive to keep up, and the architect did not consider this necessity in his

design’. ‘The gutters are asphalt with absurdly small outlets’, the

windows were leaking and the terracotta frontage with dark with grime.’

It was Nicholas Serota, appointed director in 1976, who dealt comprehensively

with the chronic financial shortage, both by securing commercial sponsorship

and increasing grant aid, and with a change in the Gallery’s constitution

allowing him to charge for exhibition entry. This made possible much-

needed improvements to the building. The first idea was to adapt the former

George Yard Mission infants school of 1886 on the west side of the Gallery

adjoining Angel Alley, a building first considered for acquisition in

1923. A feasibility study by Colquhoun & Miller, architect, in

September 1976, proposed extending the café then in what had been the small

side gallery westwards on to the site of Shaftesbury House, Angel Alley,

adding a new staircase accessing the school building. The school was to have a

ground-floor bookshop and first-floor lecture theatre whose east windows

looked down into the ground-floor gallery whose side rooflight were to be

raised to create a lightwell between gallery and school. Two bridges linked

school building and first floor gallery across this. The original staircase at

the north end, reputedly so hard to locate that some visitors missed entirely

the first-floor gallery, was to be opened into the gallery aisle. A

further scheme of December 1976 by A.J. Goddard Partnership, architects,

proposed filling in the main lightwell next to the main front staircase, with

a shop and store, and office above. A final version of the Colquhoun

& Miller scheme in January 1979 adopted this filling-in proposal and moved

the staircase to beside the main entrance, with a new lift.

In the event only minimal adaptation of the school as a lecture theatre and

bookshop was carried out , and further funds were secured over the next three

years for a new wing on its site to a design of 1982-3 also by Colquhoun &

Miller (job architect: R.J. Brearley). This was built by R. Mansell

(City) Ltd in 1984-5, necessitating closure of the gallery for a year, at a

cost of £1.6m.

The final design followed the broad principle established in 1976 but the

school and former side gallery and main staircase were replaced by a new

T-plan building, wider than the school building. This housed, on the school

site, a lecture theatre to the ground floor, with café, education room and

offices on three floors above. Adjoining to the north on the site of the old

main staircase, side gallery and part of the Shaftesbury House site were four

stories with ground-floor storage/loading bay, first-floor meeting and audio-

visual room and second-floor top-lot gallery. The two parts of the plan were

linked by a new straight east-west staircase rising east to west, made

monumental by a slight narrowing along its length, its bottom steps spilling

into the main gallery to signify its presence. The idea of shifting the

Gallery’s main front staircase to the lightwell was implemented, the space at

the front taken up with a bookshop to ground floor and workshop and mechanical

services above. The manner was 1980s Postmodern, the exterior to Angel Alley

clad in yellow brick with bands of red broadly reflecting the floor levels,

and quasi-classical oriels, that to the south front of the extension a tall,

narrow semi-cylinder, that to the west front a huge shallow bay lighting the

café. Inside small-paned semi-circular lunettes over internal doors both

referenced Harrison Townsend’s window manner, but also had a fashionable hint

of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

A doubling in size since 2001: the incorporation of the Passmore Edwards

Library

If the 1980s represented a rejuvenation for the Whitechapel Gallery through

commercial links, then the 2000s was the age of the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Although the 1984-5 extension had improved the physical environment of the

gallery and its circulation, lack of space meant it had to close for 10 weeks

a year to allow exhibitions to be installed. An opportunity to expand

arose in 2003 with the Passmore Edwards library adjoining the gallery to the

east, scheduled to close in 2005 with the opening of the new Idea Store on

Whitechapel Road and the possibility for funding from the Heritage Lottery

Fund established in 1994. A further £2.8m was raised in 2006 by a sale of work

donated by, inter alios, Damien Hirst, Lucian Freud and Julian Schabel.

Iwona Blazwick, who had become director in 2001, agreed to buy the library

building and a shortlist of architects was invited to submit ideas, with

Foreign Office Architects, Caruso St John, Patel Taylor, dRMM, Lacaton and

Vassal and Robbrecht en Daem submitting. The Belgian partnership of Paul

Robbrecht and Hilde Daem were chosen, with the help of a panel including the

artists Michael Craig-Martin and Rachel Whiteread, on the strength of their

experience in adapting existing buildings, such as the Katoen Natie cultural

centre in Antwerp, and because, as Blazwick put it, they were the only firm

not to suggest ‘bringing the street into the gallery’; she preferred that it

be a ‘refuge’, as both it and the library had been since for the people of

Whitechapel they were built.

The new layout integrated the two buildings by removing the Gallery’s 1980s

staircase, and knocking through to the entrance hall of the former library,

whose slightly higher level was maintained. This distinction of the

separateness of the buildings was underlined by the varying treatment of the

spaces, the original gallery’s architectural character generally respected

(although the entrance wall of the main gallery and its 1980s doors were

removed to increase its size), the library treated in a more interventionist

manner. This is evident in the stripping away in the former library reading

room, the main room at the rear of the ground floor, to reveal bare brick,

only the vaguely Tudoresque pilasters and columns retained. In this room large

corner pyramidal rooflights were inserted, that to the northeast corner

inverted, a Mannerist conceit, but one intended to respect the rights to light

of buildings on Osborn Street. This room became the Commissions Gallery, to

display changing installations created especially for the space. Office spaces

either side of the library’s entrance became a café, the 1980s café

overlooking Angel Alley becoming more gallery space.

The library’s existing staircase became the main access to the first floor,

with the former reference library across the front of the first floor turned

into an archive study room and archive gallery separated by a glazed wall: one

condition of the Heritage Lottery Fund grant was that the redevelopment should

include space for studying and displaying the Gallery’s archive. [Hall, op.

cit.] should make use of its archive and new access from a first floor landing

through to the original Whitechapel Gallery’s upper gallery and the library’s

former museum space, its queen-post roof with curved braces exposed. This is

the Collections Gallery, to display work from private and public collections

lacking exhibition space of their own. The most substantial changes was a new

study space added to the top floor of the library, behind the shaped gable of

the original building, made a feature hard up against the room’s south window.

This apparent retention of original fabric is in fact a reinstatement of the

gable which had been taken down in the 1970s. Large windows opposite look

across the complex roofscape of the building towards Spitalfields. Further

access to this and all floors is provided by a service stair and lift behind

the two café rooms. A further lift was added off the 1980s staircase to the

rear of the original gallery. The building was topped off by a copper and

steel weathervane by the Canadian artist Rodney Graham depicting Erasmus

riding backward on a horse, reading his The Praise of Folly.

Construction began in the summer of 2007, with Witherford Watson Mann

architects as executive partners, and Wallis Special Projects as main

contractor. The total cost of the project was £13.5m.

Rachel Whiteread's Tree of Life sculpture on Whitechapel Gallery, 2012. ©

Copyright Roger Jones and licensed

for reuse under this

Creative Commons Licence.

Since the Gallery reopened on 5 April 2009 the only substantial intervention

has been the Rachel Whiteread ‘Tree of Life’ sculpture added to the frontage

as part of the London 2012 embellishments of Whitechapel High Street for the

London Olympics. The work elaborates Townsend’s original decoration of

stylised trees, gilding some his terracotta leaves and adding gilded bronze

leaves (made in the Whitechapel Bell Foundry) cast from Townsend’s leaves, in

loose bunches (a scheme partly inspired, according to Whiteread by the

‘Hackney weed’, buddleia), breaking free from his regimented ranks of tree to

scatter across the towers and the blank panel intended for the Crane mosaic.

That panel is further embellished with four casts of the small first-floor

windows in relief, the play of negative/positive space a Whiteread signature

motif.