From Beagle House to Maersk House, 1974-2016

Contributed by Survey of London on April 10, 2017

Capitalising on London’s booming market for speculative office developments,

Seifert and Partners had grown from twelve employees in 1955 to three hundred

in 1969. Colonel Seifert estimated that his practice was responsible for over

700 office blocks and remembered of London ‘you only had to lay the first

stone and the office was let. The demand was difficult to satisfy.’ Yet

while other Seifert buildings such as Centre Point and Space House remained

controversially empty years after their opening, Beagle House’s immediate

tenancy was sure. Overseas Containers Ltd (OCL) was made up of a consortium of

four shipping companies, formed to take advantage of the new opportunities

presented by containerisation in the mid-1960s. The growth rate of OCL had

been exceptional leading to a congested head office and staff dispersed in

sub-standard City offices. Also recognising the evaporation of the initial

excitement associated with OCL’s establishment, the move to Beagle House was

designed to endear employees to stay with the company. The Board considered

that ‘provision of an optimum working environment for all levels of staff [is]

the overriding objective.’

The nine-storey office block was designed to accommodate 900 staff, with

rooftop services concealed behind an extension of the angular faceted panels

that enveloped its exterior. Some described Beagle House’s unusual plan as

lozenge shaped, others ship shaped. The building was constructed with an in-

situ reinforced concrete frame and slabs carried on piled foundations. Two

solid service and circulation cores projected outwards on the narrow east and

west ends, and eight structural columns spanned between the cores across the

centre of the open-plan office space. The ground floor receded back from the

building’s upper edge and was clad with granite, marble and mosaic. The main

elevation above first-floor level rested on oversized angular columns and

consisted of mosaic-faced precast structural mullions set with double-glazed

aluminium windows. In place of 12 to 14 Camperdown Street, a modest canteen

and garage of two storeys connected to the west end of the main block, clad in

dark purple brick and crowned with six flagpoles (see figure 3). Despite

assertions from Seifert’s staff that there was no ‘house-style’, repeated

motifs such as angled pilotis, expressive facades and rhythmic concrete

panelling are evident in many of the firm’s designs from this period. Ideas

and technical details were carried over from one building to the next along

with engineers and other design team members (figure 4). Long-time

collaborators Pell Frischmann and Partners, engineers of the Nat West Tower,

were also engaged at Beagle House. Structural glass balustrades were supplied

by Pilkington based on tests already completed at Nat West and Centre Point.

The project architect for Beagle House was Henry Grovners, who was also the

lead architect on Corinthian House in Croydon. The construction process was

not without its obstacles. The District Surveyor made several complaints about

what he saw to be the low standard of workmanship of main contractors Sir

Robert McAlpine and Sons in relation to the reinforced-concrete columns and

walls, and the project ran behind schedule.

Figure 3: Maersk

(formerly Beagle) House photographed by Derek Kendall in early 2017

Figure 3: Maersk

(formerly Beagle) House photographed by Derek Kendall in early 2017

Figure 4: Facade detail of Maersk (formerly Beagle) House photographed by

Derek Kendall in early 2017

Rather than utilise Seifert’s in-house team, OCL appointed their own interior

designers, husband and wife consultancy Ward Associates. The Wards were

favoured designers of passenger-ship interiors in the 1970s, proving

themselves capable of considerable creativity in confined spaces. As a result

of these ship interiors, Neville Ward was awarded the title of Royal Designer

for Industry in 1971. The couple shared a London office with Wyndham Goodden,

Professor of Textiles at the Royal College of Art, who designed the Chairman’s

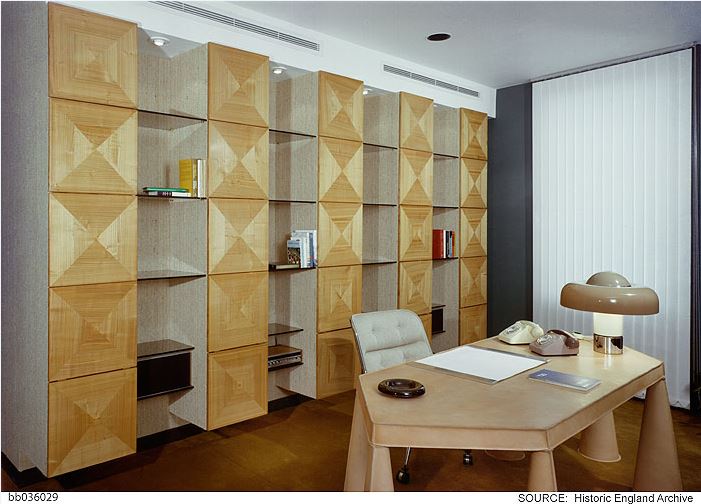

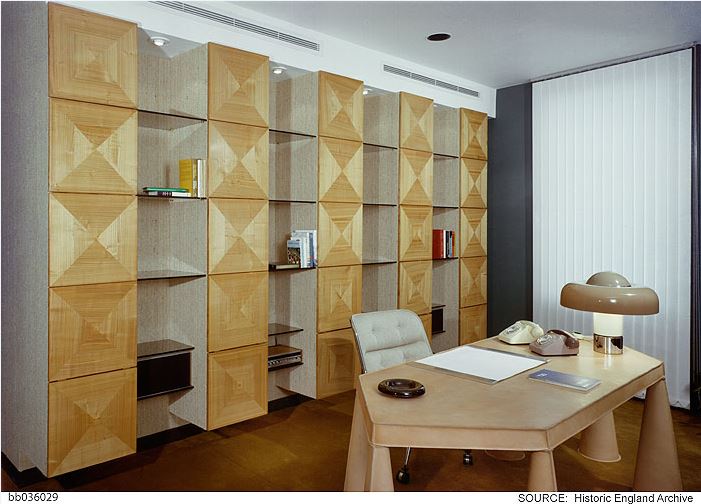

office at Beagle House (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Chairman's office designed by Wyndham Goodden. Photographed by

Millar & Harris c. 1974 (Historic England Archive, bb036029)

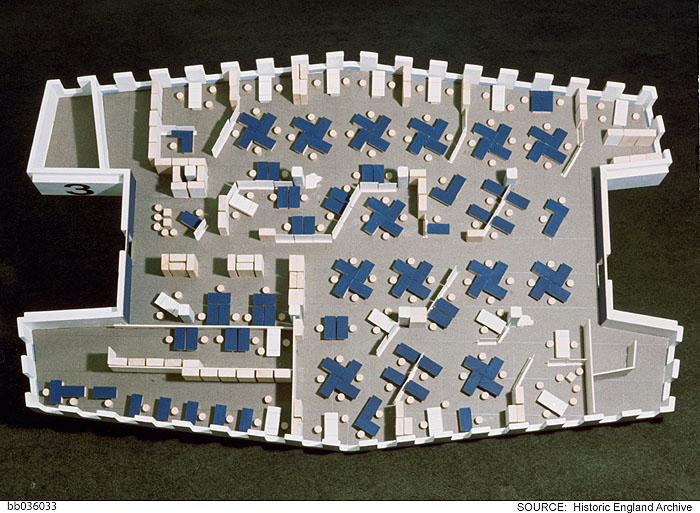

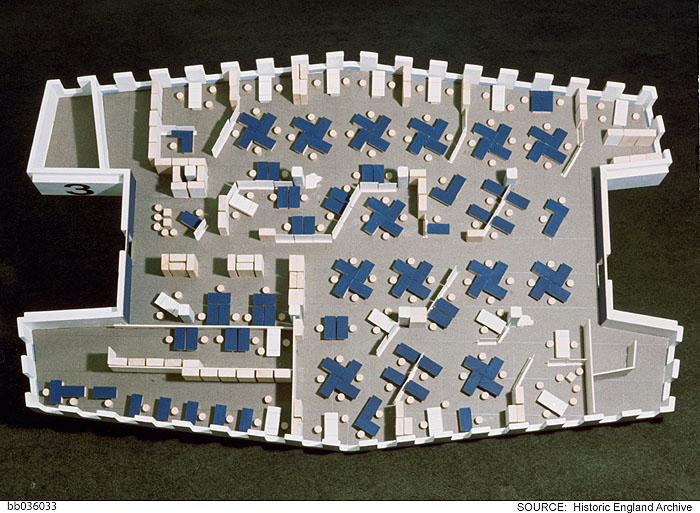

The building’s peculiar shape made provision of individual offices difficult,

only a handful were designed, those clinging to the outer corners of the

building. The open-plan interior was at first regarded as a six-month

experiment in part, to ease anxiety from middle-level managers about the shift

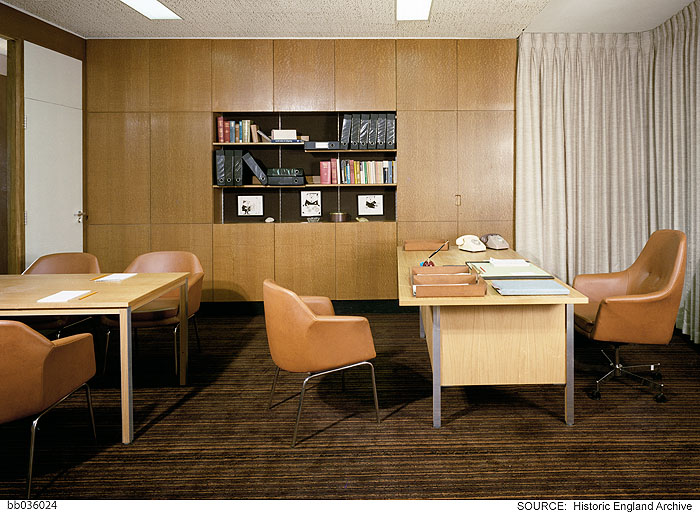

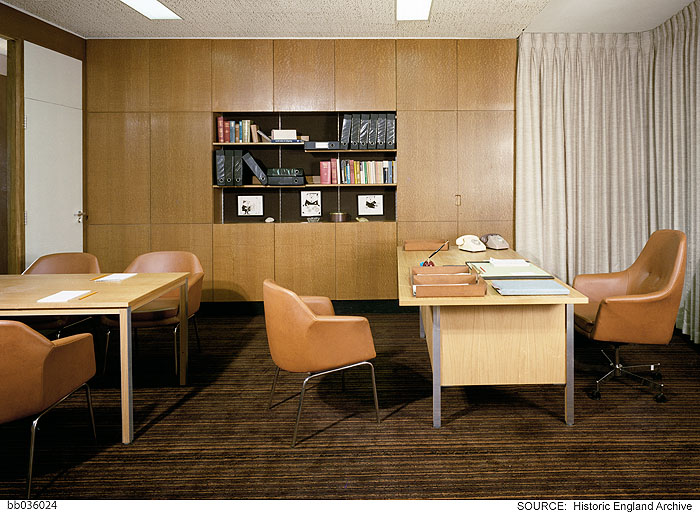

away from traditional layouts (see figure 6). The top floor however was

exclusively dedicated to upper-level management and company directors, each of

whom was afforded the privileges of a separate office illuminated by plastic-

domed roof lights and access to a serviced dining room reserved for their use

(see figure 7). Deep storage units divided each pair of offices leaving the

open-plan central space to be occupied by secretaries (figure 8). Addressing

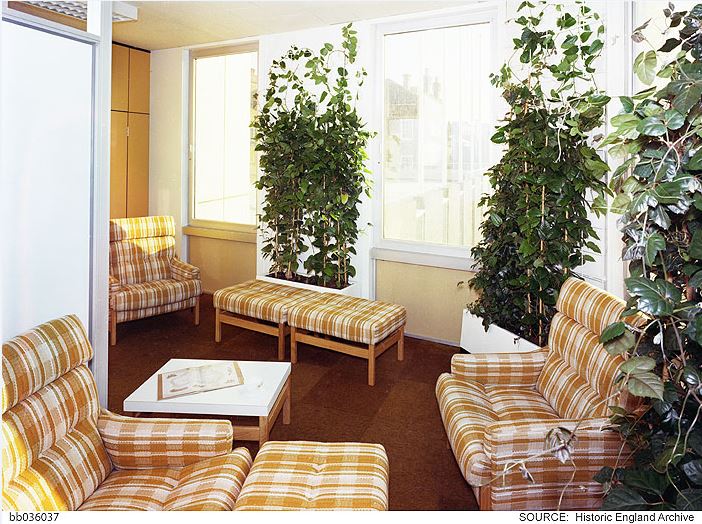

the concerns of managers on the lower floors who were uneasy about the loss of

visual and acoustic privacy, Ward Associates fashioned ‘carefully arranged

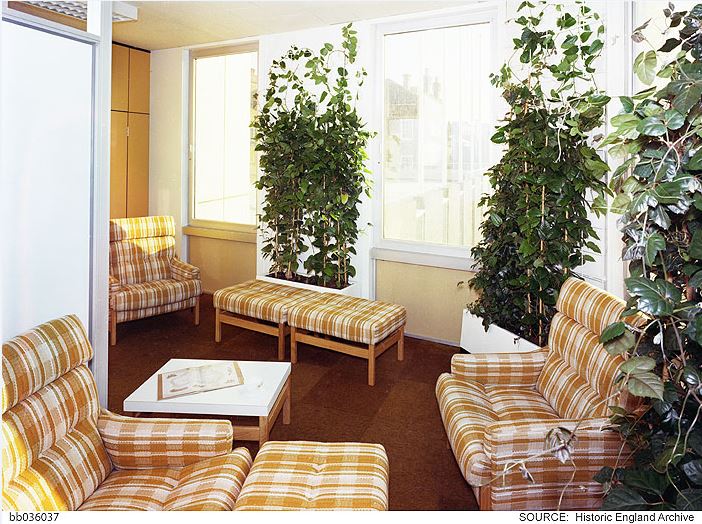

enclosures’ using screens, planting and storage cabinets (see figure 9).

Outside Beagle was skeletal and grey, while the interior was decorated in

trendy hues of brown, orange and blue, each floor differentiated by a unique

colour scheme. Floor-to-ceiling length curtains lined exterior walls and

defined meeting spaces. There were coffee areas, a lounge, snack bar and the

licensed subsidised canteen, while conference rooms were fitted with well-

stocked bars, all intended to provide OCL workers with ‘a high degree of home

comfort’ (see figure 10). As computers and machines increasingly invaded the

office environment, the interior-design press claimed that the general

introduction of plants to interiors compensated for ‘the ever increasing

emergence of soulless concrete edifices all too common today.’ They noted that

‘where a plant will survive so an office-worker’. The entrance hall was graced

with a wall-mounted model ship and an interior fish pond.

Figure 6: Ward Associates' design for a typical open-plan office floor.

Photographed by Millar & Harris c. 1974 (Historic England Archive,

bb036033)

Figure 7: Bar area for directors on the eight floor. Photographed by Millar

& Harris c. 1974 (Historic England Archive, bb036022)

Figure 8: Typical director's office on the eighth floor. Photographed by

Millar & Harris c. 1974 (Historic England Archive, bb036024)

Figure 9: Storage cabinets and plants defined spaces within the open-plan

layouts. Photographed by Millar & Harris c. 1974 (Historic England

Archive, bb036027)

Figure 10: Typical communal lounge area on open-plan floors. Photographed by

Millar & Harris c. 1974 (Historic England Archive, bb036037)

At this time interior designers were increasingly engaged in office designs

that prioritised the comfort of workers and new mechanisms for climate control

also worked to humanise working environments. Reflecting the forward-looking

spirit of OCL, the new Beagle House claimed its own technological innovations

in this respect. Writing in 1975, Interior Design regarded it as ‘London’s

first privately developed Integrated Environmental Design (IED) office

building…without a doubt, one of the most advanced buildings in the country’.

Suspended ceilings throughout Beagle House provided air-conditioning to all

spaces powered by a roof-top plant. Teething issues were resolved by

mechanical engineers Thom Benhams who were supervised by OCL’s appointed

Barlow Leslie and Partners. A resident engineer, responsible for the system’s

ongoing maintenance, was allocated a first-floor flat in the building. A press

visit in July 1974 sponsored by the Electricity Council resulted in widespread

reporting of the project in service journals. No major changes were made to

the interior layout until 1977 when the computer room doubled in size, the air

conditioning capacity was increased, and the company purchased the freehold of

Beagle House from Sterling subsidiary Town and City Properties.

One of the original four investors in OCL, P&O, secured full ownership of

the company by 1985. In 1996 what had become P&O Containers merged with

Dutch firm Royal Nedlloyd to form P&O Nedlloyd and two headquarters were

retained, one in Rotterdam, and the other at Beagle House. Following this, in

2005 PONL was taken over by their rivals Moller-Maersk and Beagle House was

renamed Maersk House.

One Braham

Contributed by Survey of London on April 10, 2017

Maersk House was demolished in 2017–18, its circumstances having altered.

Beside pedestrianized Braham Street (known as Braham Park from 2012), and no

longer locally commanding in its height nor cutting-edge in its services, it

has given way to a taller, sleeker and more tech-friendly office block with

three times the office space. After several false starts beginning in 2009,

redevelopment by Aldgate Developments, which saw through Aldgate Tower on the

other side of Braham Street in 2013–14 as Aldgate Tower Developments, was

granted planning permission in 2015. The Maersk Group moved into Aldgate

Tower, sustaining this part of Whitechapel’s shipping links. With financing

initially from Starwood Capital and then from HK Investors, the rebuild

project, dubbed One Braham, was taken forward on a design-and-build basis by

McLaughlin and Harvey, contractors, with Wilkinson Eyre, architects, and Arup,

structural engineers. One Braham went up in 2019–20 as a rectilinear glass-

faced eighteen-storey office block with ground-floor retail units.

Figure 11: Maersk House empty and cordoned off in early 2017. Photographed by

Derek Kendall

Figure 2: Photograph of Beagle

House taken from Leman Street, c. 1958 (Collage 118708)

Figure 2: Photograph of Beagle

House taken from Leman Street, c. 1958 (Collage 118708) Figure 3: Maersk

(formerly Beagle) House photographed by Derek Kendall in early 2017

Figure 3: Maersk

(formerly Beagle) House photographed by Derek Kendall in early 2017

.jpg.265x175_q85_crop-0%2C0.jpg)