St George's German Lutheran Church

Contributed by Survey of London on July 31, 2020

St George’s German Lutheran Church on the north side of what was Little Alie

Street is the oldest surviving German church in Britain. It opened in 1763,

and has changed remarkably little since. As has been said, ‘the inside keeps

the feeling of the eighteenth century in a way that few English churches

do’.

German immigration to London, much of it by Protestant refugees fleeing

religious persecution, had been significant in the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, and there were several German churches in London by 1700.

Through the first half of the eighteenth century membership of London’s German

Lutheran churches doubled to about 4,000. Some of this increase can be

attributed to the continuing immigration of those seeking religious asylum,

and the arrival of the Hanoverian Court had an additional impact. However,

economic migration was the main basis for the establishment of a German

settlement in Whitechapel. Much of the refining of Caribbean sugar imports in

London had been in German hands from its introduction in the mid seventeenth

century, expertise in processes previously established in the Hanseatic towns

being deployed to build up the sugar-baking industry that was substantially

based in Whitechapel. By the 1760s there were numerous sugarhouses in the

vicinity of Alie Street. Immigrant German sugar merchants, craftsmen and

labourers held on to the secrets of their trade, giving it continuity and

concentration in a district remote from existing German churches in the City

and Westminster.

Foundation and construction of the church

The lease of the Alie Street site was purchased for £500 on 9 September 1762

and the new church was consecrated on 19 May 1763. The principal founder was

Dietrich Beckmann, a wealthy sugar refiner, who gave £650, much the largest

single benefaction towards the total of _£_1,802 10 9 that was raised for

purchasing the lease and building the church. Beckmann (_c._1702–1766) was the

uncle of the first pastor, Dr Gustav Anton Wachsel (_c._1737–1799). The early

congregation was essentially made up of the area’s German sugar bakers and

their families, alongside some refugees escaping war in the German

provinces.

Joel Johnson built the church. He was paid _£_1,132 in 1763, which with the

lease accounted for virtually all the funds then raised. Johnson (1720–1799)

was a successful local carpenter who had made himself a contracting builder

with a large workshop at Gower’s Yard. He had probably been responsible for

the Presbyterian Chapel of 1746–7 at the west end of Great Alie Street. At the

same time he worked with Isaac Ware on the London Infirmary on Prescot Street,

and in the late 1750s he was involved in the building of the London Hospital

to Boulton Mainwaring’s designs. He was also said, in an obituary that

credited him with many chapels, to have been the architect of the church of St

John, Wapping, in 1756, a building with striking similarities to St George’s.

However, it is possible that there too he was working to Mainwaring’s designs.

Indeed, Johnson himself related that he began ‘to strike into the business of

an architect’ only in 1762. The absence of any record of payment to any other

surveyor or architect at St George’s leads to the surmise that this is what he

was doing for Alie Street’s German church. It cannot, however, be ruled out

that Johnson was working under another designer, perhaps Mainwaring again.

Johnson & Co. were paid another £_494 3_s. in 1764–5, which probably

related to an early extension of the church and the addition of the vestry

block. Seams in the brickwork of the east and west walls show that the church

was initially intended to be one bay shorter, and that during construction it

was enlarged to the north. In keeping with this vaults do not extend under the

north end of the church. It is also evident that the extension came during

rather than either before or after the fitting out of the interior. Already in

May 1763, when the church was consecrated, Thomas Johnson was being paid for a

marble slab, probably the floor of the altar dais that survives, and a

mahogany frame to a communion table. The box pews, which also survive, were

evidently in by February 1764, when Errick Kneller was paid for painting 159

numbers on them. Kneller was also paid for painting two boards, certainly

those still in place bearing the Ten Commandments in German. Kneller, not

evidently related to Sir Godfrey (Gottfried) Kneller, the German-born Court

painter, was apprenticed in London to Gerald Strong and granted his freedom

through the Painter-Stainers’ Company in 1732. Others who received payments in

1764 included Paul Morthurst, a carpenter and joiner, Thomas Palmer, a

plasterer, and Sanders Olliver, a mason. All the building tradesmen,

except perhaps Kneller, appear to have been English. Accordingly, in its

original architectural forms and constructional details, both outside and in,

the church is not evidently German. The timing of the payments suggests that

the main body of the church went up in 1762–3, the north extension following

in 1763–4, with the two-storey vestry block to the north-east being added in

1765–6, all complete by 21 August 1766, which date appears on the brick apron

of a first-floor vestry-block window, along with the names of vestrymen,

Beckmanns and Wachsels to the fore. This window faces a courtyard that until

1855 was a burial ground, the land immediately east of the church having

always pertained to it.

The front of the church to Alie Street has handsome sub-Palladian proportional

dignity, even though since 1934 it has lacked its crowning features, a clock

that was at the centre of the pediment, a bell turret above, and a large

weathervane in the shape of St George and the dragon. In its original form

this elevation bears out a link with St John Wapping. The two uppermost stages

of the former turret were smaller versions of the upper stages at Wapping, and

both churches had identical eyebrow cornices over their clocks. The central

lunette below may once have been glazed, though an organ soon blocked it. Its

present lettering, ‘Deutsche Lutherische St Georg’s Kirche Begründet 1762’ in

Gothic script, is a renewal of an earlier inscription. The other elevations of

St George’s are plain. East of the church on Alie Street was Wachsel’s

substantial three-storey pastor’s house, replaced by a school building in

1877.

Church interior

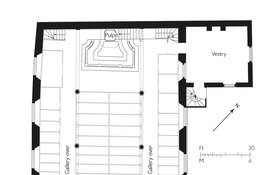

Little has been taken away from the interior of the church that was built in

the 1760s. The furnishings are remarkably unchanged. Box pews still fill the

floor, and the galleries that stand on eight Tuscan timber columns still line

three sides of the building. With a simple Protestant layout, the most has

been made of limited space. There is no central aisle, and more of the

building’s width is galleried than is not.

Past this density the eye is drawn to the north (liturgically east) wall and

its essentially original ensemble of pulpit, commandment boards and royal

arms. The central pulpit stands above and immediately behind a railed altar,

in an arrangement that is typically Lutheran. To emphasise the interdependent

centrality of preaching and sacrament in its worship Lutheranism tended to

favour bringing the altar and the pulpit as close together as possible, often

with the altar raised on a dais, as it is here. The pulpit, raised to

allow the pastor to address the galleries as directly as the rest of the

congregation, comprises a shaped desk with a backboard and a large tented

canopy or tester, atop which there flies a dove. It has always been approached

by the stairs to its east, but to start with it would have seemed less hemmed

in, apparently floating above the altar against the panelled back wall. The

altar dais was originally relatively small, three steps up, with a black-and-

white pattern marble floor. Originally the turned-baluster communion rails

were on the outer edge of a large second step that was wide enough for the

pastor to walk round.

In a prominent position above the pulpit are the splendid gilt Royal Arms of

King George III, in the form that they took up to 1801, presumably work of the

1760s. Unique in a German church in England, these arms seem to be a clear

assertion of loyalty to the Crown on the part of Whitechapel’s German

community. However, it should be noted not only that King George was the

Elector of Hanover, but also that, however genuine and general loyalty might

have been, there was opposition from a majority of the congregation to

Beckmann and Wachsel’s preference for use of the English language. Through

these Arms the founder and pastor may have been making a point. Flanking the

tester are the sumptuously framed commandment boards, their gilt texts in

German, exquisitely lettered by Kneller in 1763–4.

The entrance vestibules both retain original staircases, with closed strings

and turned column-on-vase balusters, solid joinery if somewhat old-fashioned

in the 1760s. A blocked doorway under the south-east staircase originally led

directly into the pastor’s house. Panelling along the side walls, which breaks

before the north bay, in line with external seams in the brickwork, and steps

down at the same point in the galleries, indicate the late change of plan that

extended the church northwards in 1763–4. Above a restored ceiling there is a

timber king-post truss roof that is essentially that built in the 1760s. The

roof space also retains fittings for the support of a central chandelier, long

gone and of which no depictions are known. The first-floor committee room in

the vestry block retains its eighteenth-century plain panelled walls, cornice

and fireplace surround.

Late Georgian conflicts and alterations

Beckmann died in 1766, leaving the church a further £_500. On the north wall

near the reader’s stairs there is a commemorative tablet in English, to him,

his sons and his wife, and there is also a floor slab in front of the

sanctuary; he is said to have been buried under the communion table. Despite

having been enlarged during construction the church was soon found to be too

small to meet early demand. There was overcrowding in 1768, many worshippers

being forced to stand at the back. Another legacy of Beckmann’s was

disagreement between his nephew, Wachsel, and another nephew, Nicholas

Beckmann, who had the support of other vestrymen. This dispute about authority

led to a violent confrontation in the church on 3 December 1767. Wachsel saw

his opponents off, but from 1770 found himself embroiled in a wider and long-

lasting _Parteienkrieg, as it was called, that extended to liturgy and the

nature of music in the church, as well as to the question of whether services

should be held in English or in German. In spite of his theological roots in

German Pietism, which had moved away from complex church music, Wachsel

introduced hymns, first in German then in English, and then sermons in

English. Next he discharged a German choir and introduced ‘violins, trumpets,

bassoons, and kettledrums’. The musical performances were said to have been

accompanied by the eating of ‘Apples, Oranges, Nuts etc as in a Theatre’. The

church allegedly ‘became a place of Assignation for persons of all

descriptions a receptacle for Pickpockets and obtained the name of the Saint

George Playhouse Goodman’s Fields’.

Amid fights and death threats a congregation that had been more than 400 had

fallen to 130 by 1777. Despite an overwhelming vote for his dismissal in 1778

Wachsel held on to his post by going to law. Acrimony rumbled on. Having

desisted for a time, Wachsel reintroduced music in 1786. At this point he was

accused of violently assaulting the bellows blower. Another judicial

intervention in 1789 ruled that Wachsel had misused the building, but

arguments about the use of English continued up until his death in 1799.

Wachsel has a humble plaque on the east wall, its inscription in English.

Early alterations to the fittings at the north end of the church may have to

do with this power struggle. In 1784 a payment was made towards ‘a Cloth

Communion Table’, seemingly identifiable as the canvas reredos, a

surprising survival, that is gilded with vine leaves and the text of John

14.6, in German within a laurel wreath. At some point after this reredos was

installed and before 1802, possibly in the late 1790s, the already small

railed sanctuary was made smaller. The communion rails were moved marginally

in on all three sides, and the dais was enlarged with a timber extension to

meet the rails. This brought communicants closer to the altar, but

accommodated fewer. This might be explained through Pietism, which would have

stressed preaching and personal devotion while de-emphasising weekly

communion, or it might have been simple pragmatism. It may be relevant that in

1796 £_55 2_s. 6_d._ was spent on ‘repairing and fitting up the chapel,

parsonage and other appurtenances’.

At the other end of the church there were two small curved-front upper

galleries, possibly for children or a children’s choir, on columns to either

side of a small organ. It is possible that these were always present, but

given the blocked lunette it is likely that they were an early change, perhaps

from the late 1760s when there was great demand for seating, or from 1778–9

when small sums were spent repairing the church. The account of the

Parteienkrieg indicates that there was an organ by 1786. An organ was

explicitly present in 1802 when reader’s and clerk’s desks were fixed

immediately west of the pulpit. The reader’s desk, at least, was being

relocated. Its previous mobility is evident in the survival of casters on the

bases of its corner posts.

Benefaction boards at the south end of each outer row of pews commemorate many

gifts to the church, including a _£_50 donation from King Frederick William IV

of Prussia in 1842. Through the long pastorate of Wachsel’s successor, the

Rev. Dr Christian E. A. Schwabe, from 1799 to 1843, during which services were

in German, the German community in Whitechapel continued to grow, and other

German churches were established near by. A German Catholic church with its

origins in Wapping in 1808 moved to its present location on Mulberry Street

and Adler Street in 1861 where the Church of St Boniface continues. St Paul’s

German Protestant Reformed Church opened on Hooper Square in 1819. This

congregation, its church rebuilt on Goulston Street in 1887 and destroyed in

1941, was thereafter merged into that of St George’s.

Restoration of the church in 1855

A framed tablet under St George’s west gallery, put up in 1856 and made by a

Mr Cook for £_5 14_s., has a painted inscription that explains in German

changes that had then taken place. Translated it relates: ‘1 SAM 7.12/

Hitherto hath the Lord helped us/In the year 1855/through voluntary

contributions from the members of this parish and German and English friends

the sum of £_2465 18_s. was collected in a few weeks and administered by

John Davis as Treasurer. With this sum the church was completely renovated and

beautified, the foundations for the capital assets of the parish lain, and the

continuance of this place secured for many years.’ This happened under the

leadership of Dr Louis Cappel (1817–1882), pastor from 1843 to 1882, who had

come from Worms and who was of Huguenot descent.

The restoration of 1855 arose from the renewal of a sixty-one-year lease that

had been acquired in 1802. Successful fund-raising was broadly based,

seemingly drawing primarily on Whitechapel’s still strong sugar-baking German

community. It remained the case that ‘the Elders and Wardens of the Church

consist almost exclusively of the Boilers, Engineers and superior workers in

the Sugar Refineries’. Mid nineteenth-century attendances were said to be

about 400 to 500, of which about 250 paid pew rents. A sub-committee of five

led by Cappel managed the restoration; three of the others – Martin Brünjes,

William Prieggen and Claus Bohling – were local sugar refiners. The church was

closed for the building works during July and August 1855. Costs escalated and

legal difficulties held up renewal of the lease; it was September 1856 before

the congregation was asked ‘to bear testimony to the present condition of the

building and the propriety of its decoration’.

The works had been supervised by J. Cumber, who was also surveyor to the

Phoenix Fire Office,and £_540 was paid to the builders, William Hill and J.

Keddell. In all £_771 was spent on the restoration of the church, which

included complete refenestration and redecoration.

Cast-iron framed side-wall and south gallery windows with red and blue margin

glazing replaced original leaded-light windows. In addition James Powell &

Sons of Whitefriars were paid _£_53 for two stained-glass windows that were

designed by George Rees. These were a Crucifixion and an Ascension that

originally flanked the commandment boards at the north end of the church. In

1912 the Ascension was destroyed and the Crucifixion was moved to the south

wall, reorganised to fit into a three-light opening. There it retains borders

of stamped jewel work that are the first recorded instance of a technique that

became a Powell speciality.

The redecoration of 1855 included the marbling of the columns, the graining

and re-numbering of the pews, replacement of some top rails in mahogany, the

removal of lamp or sconce holders (leaving mortices that can be seen to have

been filled), and the removal of latch and lock plates. A large pew to the

north-west was divided, cut down in height, cut back and carefully repaired so

as to leave little trace of alteration. The enduring numbering of the pews and

the survival of the church archives make it possible to trace who sat where in

the church. The clerk’s desk was removed, its lectern being shifted to the

east side, seemingly for the sake of visual symmetry. The stairs to the

reader’s desk thus had to be remade, and it appears that the cheek-pieces and

balustrade of those leading to the pulpit were also similarly remade. On the

south-west gallery staircase Greek-key-pattern linoleum may also survive from

1855 as may self-closing mechanisms on the vestibule doors leading into the

church. Finally, the vestry block’s winder staircase, previously timber

framed, was enclosed in brick.

Given the extent and considerable expense of this restoration it is notable

that the interior was not more substantially altered, particularly when the

generally radical and doctrinaire character of mid nineteenth-century English

church restorations is recalled. Box-pew seating was reviled by the

contemporary Anglo-Catholic revival, but there is no reason to suppose

ecclesiological influence in a German Lutheran church. Indeed, there was no

Catholic revival in Lutheranism until the early twentieth century, and

iconoclastic attitudes persisted through the nineteenth century.

Lutheranism aside, conservatism in church liturgy and architecture is entirely

to be expected in an enclosed immigrant group like the Whitechapel German

community. After the late eighteenth-century Parteienkrieg over the

introduction of Anglican style worship the conservatism of the 1850s perhaps

reflected a conscious desire to steer away from any kind of liturgical

innovation, especially any that might be connected to Anglicanism.

The church from 1855 to 1930

There was little physical change to the church through the rest of the

nineteenth century. The organ in the south gallery was replaced in 1885–6,

the new instrument also displacing the upper galleries in works supervised by

E. A. Gruning, the German architect of the church’s new schools (see below).

Made by E. F. Walcker, then of Ludwigsburg, for _£_353, this organ survives,

in an enlarged form following repairs carried out by the same firm in 1937. It

was restored by Bishop & Son in 2003–4.

The giving up of the upper galleries and the earlier removal of a pew behind

the southernmost columns suggest declining attendances in the late nineteenth

century. From the 1860s the local sugar industry saw dramatic decline, and

many of those who could afford to do so moved away from Whitechapel. However,

London’s German population as a whole almost doubled in the half century to

1911. Whitechapel’s German residents were now occupied across a range of

trades. From 1891 to 1914 Pastor Georg Mätzold (1862–1930) rebuilt the

congregation and in the years up to 1914 St George’s was said to be the most

active German parish in Britain, with average congregations of about 130.

Repairs undertaken in 1910 under the supervision of Frederick Rings, another

German architect, by G. J. Howick, a Catford builder, included the replacement

of the vestry windows with ‘“Stumpfs” Reform Sash Windows’, made to the

patented designs of Abdey, Hasserodt and Co., ‘builders of portable

houses’. In 1912 a fire in the building adjoining to the north led to

the replacement of the Powell windows with stained glass by Heaton, Butler and

Bayne, again depicting the Crucifixion and Ascension. Other acquisitions from

this period were a silver orb with an engraving of the façade of the church, a

brass cross and candlesticks for the altar, probably designed by Alexander

Koch (1848–1911). Kaiser Wilhelm II donated a bible in 1913.

The First World War was a difficult time for Whitechapel’s Deutsche Kolonie.

Many of the congregation’s members returned to Germany in 1914, and others

were interned. Mätzold stayed and continued services in the church, also

taking on a pastoral role in internment camps. Continuity broke down in 1917

when the school was forced to close and Mätzold was expelled from the country.

He was unable to return until 1920, from which date he quietly held together a

much-diminished congregation until his death in 1930.

The church after 1930

Part of Mätzold’s caution through the insecure 1920s had been the deferral of

necessary maintenance. His successor, Dr Julius Rieger, from Berlin, was

obliged to undertake an extensive programme of repair work in 1931, moving

gradually as funds became available. Rieger took an early opportunity to pay

tribute to his predecessor. The south end of the church under the gallery was

re-organised in 1932 to create a committee room that was inaugurated and

remains known as the Mätzoldzimmer. The formation of this room involved the

loss of two large pews and circulation space as the panelling on the inner

sides of the two entrance passages was extended northwards as far as the

southern pair of columns. The eighteenth-century panelled partition that

encloses the north side of the committee room has been turned around to

present its fair raised-and-fielded face to the room rather than to the

church. Pews on the other side of the columns were taken out, to create a

narrow passage between the committee room and the remaining pews. Another more

southerly pew had already been removed.

In 1934 W. Horace Chapman, architect, conducted investigations of the roof and

turret that discovered rot and woodworm. On the instructions of F. W. Charles

Barker, Whitechapel’s District Surveyor, the bell turret and the coved ceiling

were dismantled by J. Jennings & Son Ltd.

By this time Rieger had more to worry about than woodworm. Adolf Hitler’s rise

to power in 1933 presented expatriate Germans with dilemmas. Rieger was an

associate of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945), a young but eminent theologian

and opponent of National Socialism, who served from 1933 to 1935 in London as

pastor to German congregations in St Paul, Goulston Street, and in the German

Evangelical Church in Sydenham. Rieger’s parish became a relief centre,

providing a base for advice and shelter for German and Jewish refugees,

particularly children, also sending off references for travel to England.

During the Second World War German churches in Britain were not generally

persecuted as they had been in 1914–18. It is nonetheless notable that at St

George’s services continued uninterrupted right through the war. The church

escaped significant bomb damage and was kept full into the 1950s, London’s

German community having then been reinforced by a new wave of refugees.

Rieger’s successor in 1953 was Pastor Eberhard Bethge, Bonhoeffer’s student,

friend and biographer. His mentor had been hanged in April 1945 at Flossenburg

concentration camp.

Attendance at St George’s declined in the later decades of the twentieth

century. In 1970 plans were drawn up by J. Antony Lewis, architect, proposing

a major re-ordering that would have removed the pews and all but the west

gallery, but this was not carried through. In 1996, when there were only about

twenty left attending regularly, Pastor Volkmar Latossek led the congregation

into a merger with that of St Mary’s German Lutheran Church, Bloomsbury.

St George’s Church was facing an insecure future. The Historic Chapels Trust,

established in 1993 to protect disused non-Anglican places of worship, took it

into care in 1996, and an extensive restoration programme costing _£_866,000

was carried out in 2003–4. This was supported by grants from the Heritage

Lottery Fund, English Heritage, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, St Paul’s

German Evangelical Reformed Church Trust, and other private donations. Thomas

Ford & Partners (Daniel Golberg and Brian Lofthouse) were the architects,

and the building contractors were Kingswood Construction. The work included

the reinstatement of a coved ceiling, like that removed in 1934. Reinstatement

of the tower was also considered, but grant support for that was not

forthcoming.

The Historic Chapels Trust used the vestry as an office from 2005 and

established a local committee for St George’s that arranged concerts, lectures

and other activities in the building. The former congregation has had leave to

use the church for occasional services of worship. Since 2018 the Churches

Conservation Trust has supported the Historic Chapel Trust’s continuance.