Posted by Survey of London on June 5, 2017

On Saturday 3rd June we held a fascinating workshop on personal and family histories of Whitechapel at the Tower Hamlets Archives on Bancroft Road. The event was attended by a range of people who represented diverse strands of Whitechapel’s history. Here’s a quick summary of some of the stories we listened to, to give you a flavour of the day:

Sufia Alam opened the session by narrating the story of how her father settled first in Princelet Street in the 1960s, before moving to Yorkshire with his young family. Her uncle remained in the East End, and Sufia and her family would spend summers in Whitechapel where they felt a great connection with the place and the Bangladeshi community living there. After her marriage Sufia moved back to East London and has spent the last 20 years working in local womens’ organisations, including the Jagonari Centre, and she is now the manager of the East London Mosques’s Maryam Centre from where she continues to run programmes for local women.

Another participant, Jackie, grew up on Petticoat Lane in the 1950s and reminisced about how the lanterns on the market stalls were lit up as night fell, as well as eating a lot of smoked salmon. She remembered there were many shoe shops on the street as well as a grocers which was very well known, Mossi Marks, located on the corner of Wentworth Street and Toynbee Street.

Eleanor Leverington has memories of a happy childhood in Whitechapel before moving later in life further east. Her mother Pat, who also spoke at the event, migrated to the East End from Ireland in 1950. Reflecting back over many years, she felt that Whitechapel has provided a fulfilling home for her and her five children. Meanwhile Denis cast his mind back to his early years growing up on Anglesea Street and attending the well-known Brady Boys' Club.

Also a long-standing resident of the area, Stanley Meinchick and his wife’s wedding was the last to be held at the New Road Synagogue in 1973, he remembered that it was such a small synagogue that they had to walk down the aisle one behind the other.

Rosemarie Wayland recalled a visit to the home in Old Montague Street of the first Bengali girl to arrive in her class, around 1960. She remembers the girl's mother giving her Jacob's Cream Crackers with strawberry jam, to make her feel at home with "English food", which disappointed Rosemarie whose mouth was watering at the smell of the spicy food the woman was cooking.

Tony Wetjen, spoke about his research into the history of his family, who settled in Whitechapel after arriving from Germany several generations ago. His was one of many families who arrived to work in the sugar refining industry locally. He uncovered the mystery of his Norweigan-sounding surname which he found had been adopted during the First World War to deflect anti-German feeling. As he pointed out, it was a strategy adopted by our own Royal Family when they changed their name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to the more English (and manageable) Windsor.

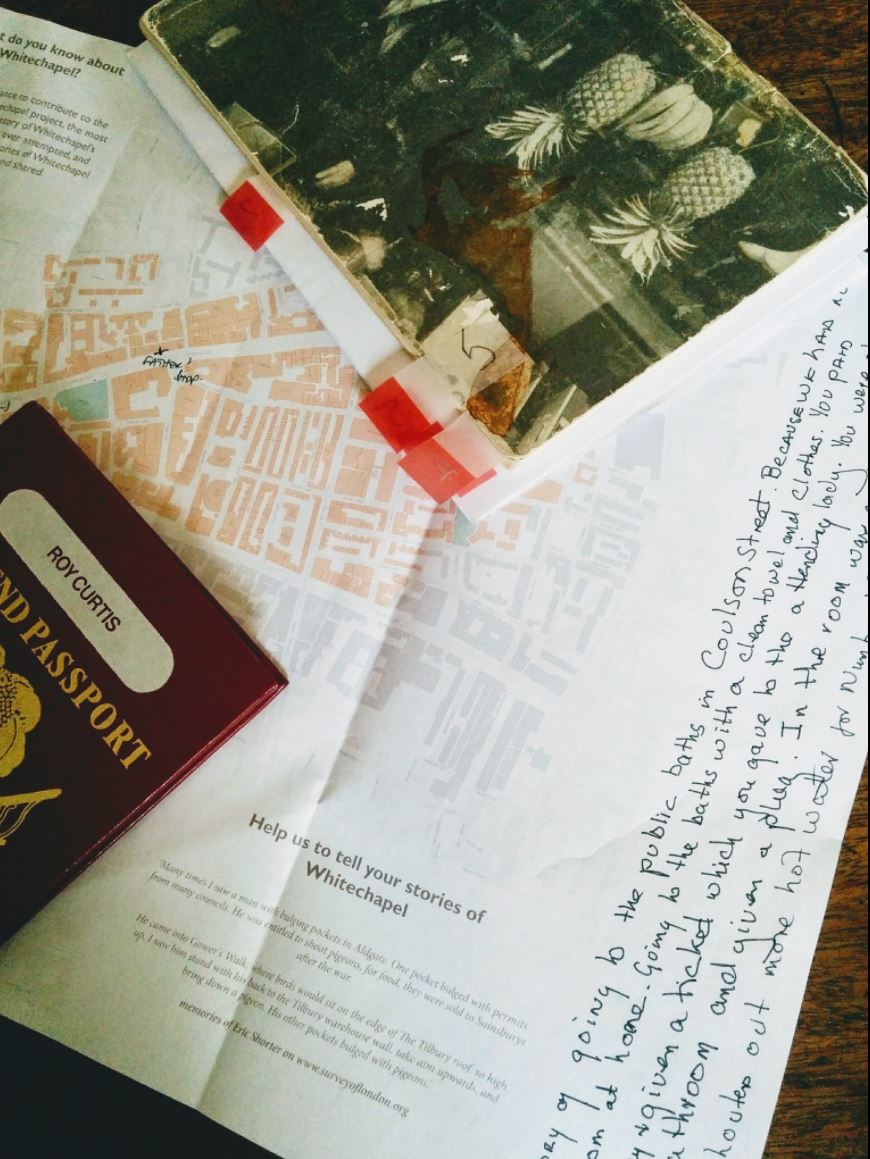

We are collating the many memories shared, and linking them to sites in Whitechapel to be put onto our map. We are always on the look-out for more, so do contribute yours, either online or simply send us an email.

Posted by Survey of London on June 1, 2017

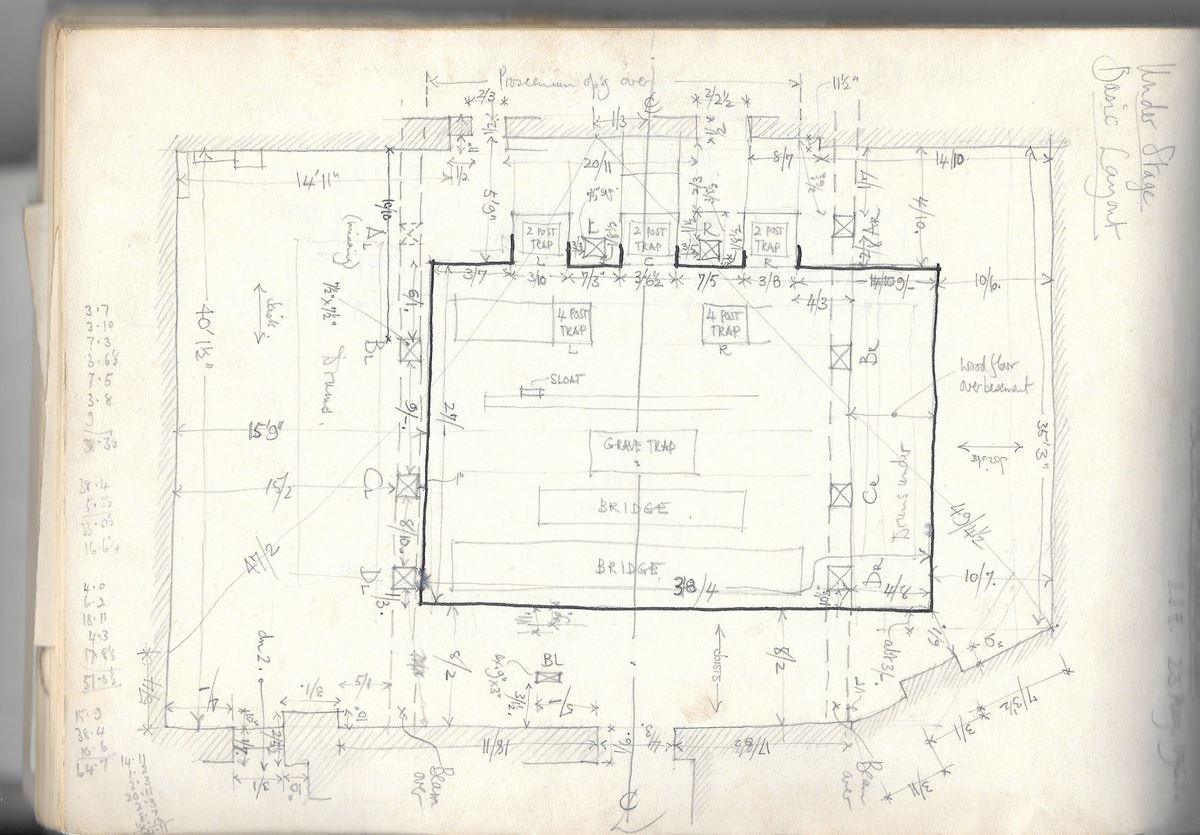

John Earl, doyen among historians of theatres, remembers recording the derelict remains of the Whitechapel Pavilion in 1961:

It was a dauntingly complex task, as to my (then) untrained eye, it appeared to be an impenetrable forest of heavy timbers, movable platforms and hoisting gear, looking like the combined wreckage of half a dozen windmills! I started by chalking an individual number on every stage joist in an attempt to provide myself with a simple skeleton on which to hang the more complicated details. Richard Southern's explanations enabled me to allocate names to the various pieces of apparatus, correcting my guesses. (‘Stage basement’ for example was, I learned, an imprecise way of naming a space with three distinct levels). He also gave me a brilliant introduction to the workings of a traditional wood stage and to the theatric purposes each part fulfilled.

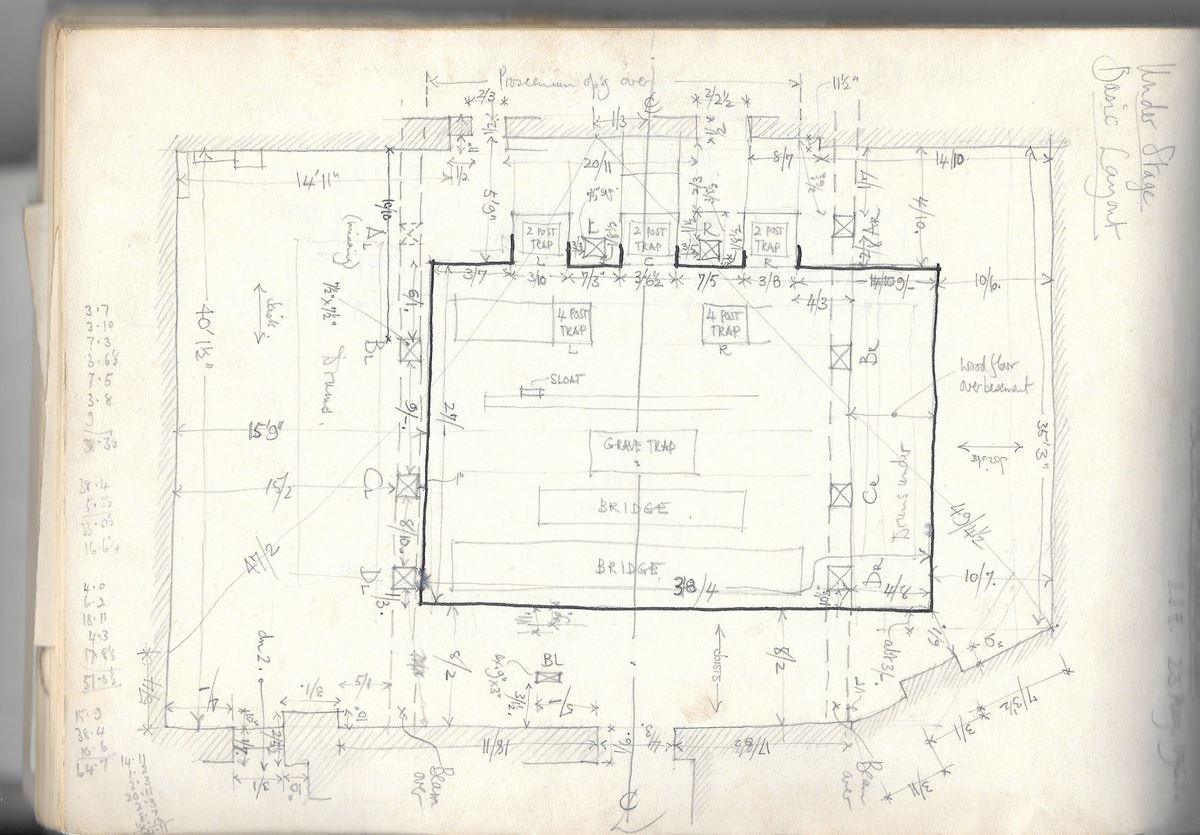

The attached sketch attempts to give a summary view of the entire substage.

It is set at the first level below the stage, with the proscenium wall at the top and the back wall of the stage house at the bottom. In the terminology of the traditional wood stage, this is the ‘mezzanine’, from which level, all the substage machinery was worked by an army of stage hands. In the centre, the heavily outlined rectangle is the ‘cellar’, deeper by about 7ft below the mezzanine floor. Housed in the cellar are a variety of vertically movable platforms designed to move pieces of scenery and complete set pieces.

It may be observed at this point that not all of this apparatus will have resulted from one build. A wood stage had the great advantage that it could be adapted at short notice by the stage carpenter to meet the demands of a particular production. The substage, as seen, represents a particular moment in its active life.

There are five fast rise or ‘star’ traps for the sudden appearance (or disappearance) of individual performers (clowns, etc) through the stage floor. The three traps nearest to the audience are ‘two post’ traps, rather primitive and capable of causing serious injury to an inexpert user. Upstage of these are two of the more advanced and marginally safer ‘four post’ traps. In both types, the performer stood on a box-like counter-weighted platform with his (usually his) head touching the centre of a ’star' of leather-hinged wood segments. Beefy stage hands pulled suddenly (but with split second timing) on the lines supporting the box, shooting him through the star. In an instant, it closed behind him, leaving no visible aperture in the stage surface.

Farther upstage is a row of ’sloats’, designed to hold scenic flats, to be slid up through the stage floor. Next comes a grave trap which, as the name suggests, can provide a rectangular sinking in the stage (‘Alas, poor Yorick’). Finally, a short bridge and a long bridge, to carry heavy set pieces, with or without chorus members, up through (and, when required, a bit above) the stage. These bridges were operated from whopping great drum and shaft mechanisms on the mezzanine.

In order to get all these vertical movements to pass through the stage, its joists, counter-intuitively, have to span from side to side, the long span rather than the more obvious short span. This makes it possible to have removable sections ‘(sliders’) in the stage floor, which are held level position by paddle levers at the ends. When these are released, the slider drops on to runners on the sides of the joists and are then winched off to left and right.

The survey of the Pavilion stage was important at the time because it seemed to be the first time that anything of the kind had been done, however imperfectly. Since then, we have learned of complete surviving complexes at, for example, Her Majesty’s theatre in London, the Citizens in Glasgow and, most importantly, the Tyne theatre in Newcastle, which has been restored to full working order twice (once after a dreadfully destructive fire) by Dr David Wilmore. Nevertheless, the loss of the archaeological evidence of the Pavilion is much to be regretted.

I can have enjoyable fantasies about witnessing an elaborate pantomime transformation scene from the mezzanine of a Victorian theatre. The place is seething with stage hands, dressers and flimsily clad chorus girls climbing on to the bridges, while the stage is shuddering, having been temporarily robbed of rigidity by the drawing off of the sliders. Orders must be observed to the letter and to the very second, but there can be no shouting, however energetically the orchestra plays. Add naked gas flames to the mix…

That's enough!