Recording the Pavilion Theatre in 1961

Posted by Survey of London on June 1, 2017

John Earl, doyen among historians of theatres, remembers recording the derelict remains of the Whitechapel Pavilion in 1961:

It was a dauntingly complex task, as to my (then) untrained eye, it appeared to be an impenetrable forest of heavy timbers, movable platforms and hoisting gear, looking like the combined wreckage of half a dozen windmills! I started by chalking an individual number on every stage joist in an attempt to provide myself with a simple skeleton on which to hang the more complicated details. Richard Southern's explanations enabled me to allocate names to the various pieces of apparatus, correcting my guesses. (‘Stage basement’ for example was, I learned, an imprecise way of naming a space with three distinct levels). He also gave me a brilliant introduction to the workings of a traditional wood stage and to the theatric purposes each part fulfilled.

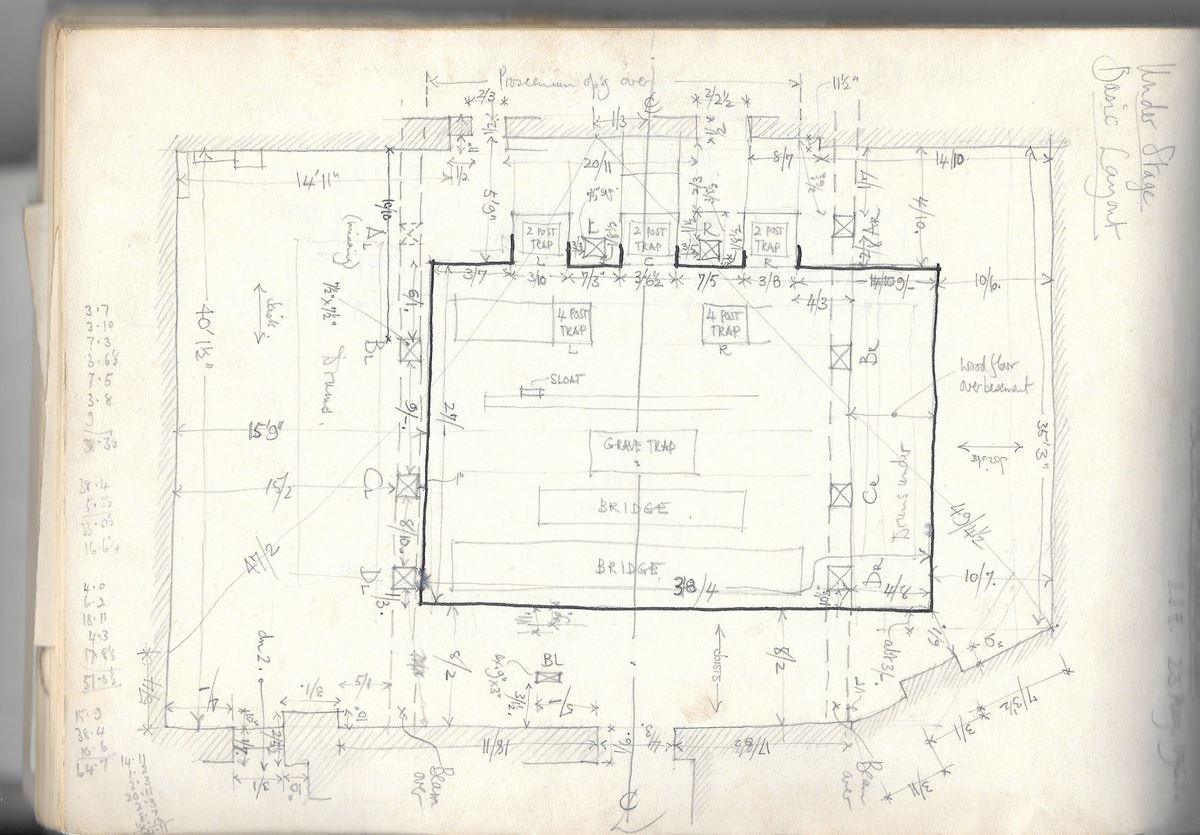

The attached sketch attempts to give a summary view of the entire substage.

It is set at the first level below the stage, with the proscenium wall at the top and the back wall of the stage house at the bottom. In the terminology of the traditional wood stage, this is the ‘mezzanine’, from which level, all the substage machinery was worked by an army of stage hands. In the centre, the heavily outlined rectangle is the ‘cellar’, deeper by about 7ft below the mezzanine floor. Housed in the cellar are a variety of vertically movable platforms designed to move pieces of scenery and complete set pieces.

It may be observed at this point that not all of this apparatus will have resulted from one build. A wood stage had the great advantage that it could be adapted at short notice by the stage carpenter to meet the demands of a particular production. The substage, as seen, represents a particular moment in its active life.

There are five fast rise or ‘star’ traps for the sudden appearance (or disappearance) of individual performers (clowns, etc) through the stage floor. The three traps nearest to the audience are ‘two post’ traps, rather primitive and capable of causing serious injury to an inexpert user. Upstage of these are two of the more advanced and marginally safer ‘four post’ traps. In both types, the performer stood on a box-like counter-weighted platform with his (usually his) head touching the centre of a ’star' of leather-hinged wood segments. Beefy stage hands pulled suddenly (but with split second timing) on the lines supporting the box, shooting him through the star. In an instant, it closed behind him, leaving no visible aperture in the stage surface.

Farther upstage is a row of ’sloats’, designed to hold scenic flats, to be slid up through the stage floor. Next comes a grave trap which, as the name suggests, can provide a rectangular sinking in the stage (‘Alas, poor Yorick’). Finally, a short bridge and a long bridge, to carry heavy set pieces, with or without chorus members, up through (and, when required, a bit above) the stage. These bridges were operated from whopping great drum and shaft mechanisms on the mezzanine.

In order to get all these vertical movements to pass through the stage, its joists, counter-intuitively, have to span from side to side, the long span rather than the more obvious short span. This makes it possible to have removable sections ‘(sliders’) in the stage floor, which are held level position by paddle levers at the ends. When these are released, the slider drops on to runners on the sides of the joists and are then winched off to left and right.

The survey of the Pavilion stage was important at the time because it seemed to be the first time that anything of the kind had been done, however imperfectly. Since then, we have learned of complete surviving complexes at, for example, Her Majesty’s theatre in London, the Citizens in Glasgow and, most importantly, the Tyne theatre in Newcastle, which has been restored to full working order twice (once after a dreadfully destructive fire) by Dr David Wilmore. Nevertheless, the loss of the archaeological evidence of the Pavilion is much to be regretted.

I can have enjoyable fantasies about witnessing an elaborate pantomime transformation scene from the mezzanine of a Victorian theatre. The place is seething with stage hands, dressers and flimsily clad chorus girls climbing on to the bridges, while the stage is shuddering, having been temporarily robbed of rigidity by the drawing off of the sliders. Orders must be observed to the letter and to the very second, but there can be no shouting, however energetically the orchestra plays. Add naked gas flames to the mix…

That's enough!