20-27 Wentworth Dwellings

1980s brown brick flats with shop units to ground floor, and school to Goulston Street. On site of Davis Mansions | Part of Goulston Street Improvement

Peter Martineau's Sugarhouse

Contributed by Survey of London on March 9, 2017

The sugar refining industry in England began in the 1540s when Cornelius Bussine, a citizen of Antwerp with knowledge of the ‘secret’ art of sugar refining, established the first sugarhouse within the City of London. Several more followed, but it was not until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that the business of sugar refining truly gathered pace in London. By 1750 there were said to be eighty sugarhouses in the capital and a further forty dispersed across the rest of England and Scotland. In spite of the noxious nature of the industry and the propensity of its buildings to catch fire, most of these London refineries were still then located within the City walls, close to the Thames or Fleet rivers. However, the opening of the West India Docks in 1802 lured the sugar trade east and a ruling by the Court of Common Council in 1807 finally forbade sugarhouses to remain within the City. At the close of the eighteenth century suburbs already claimed a number of well- established sugarhouses owing to comparative openness and access to the Port, but in the early nineteenth century these distinctive buildings, and the cramped lodgings of their workers, became defining features of the parishes of Whitechapel and St George in the East. This shift eastwards coincided with a renewed wave of German immigration following that of the eighteenth century. Skilled and unskilled sugar workers as well as ambitious businessmen arrived from Northern Germany helping to transform the industry from a collection of small-scale enterprises, reliant on a high degree of manual operations, to a relatively industrialised and technologically advanced industry, both dynamic and lucrative as a result of the nearly unrivalled British consumer market.1

George Martineau, a descendant of one East End family of sugar refiners, reflected that “in 1856….practically all the loaf sugar consumed in this country was produced in the East End of London.” The 1851 census demonstrated that over 90% of those engaged in the London sugar-refining trade were resident in the borough of Stepney. Whilst the London sugar industry experienced a period of particularly profitable expansion in the 1860s and 1870s such extravagant prosperity did not last. Whereas 1864 could claim twenty-eight London sugarhouses, by 1880 only twelve remained. Affected by duties, the rise of beet sugar and proximity to Continental competition, the East End industry slumped, giving way to Liverpool and Greenock, which were better placed for Caribbean imports once London’s monopolies were loosened, before nationally subsiding not long after. Building new refineries on the banks of the Thames in the 1870s, Tate and Lyle of Silvertown are the sole survivors of this East End industry, having cannily diversified into syrup and been early backers of the newly invented sugar cube. A single functioning sugarhouse lasted into the twentieth century in Whitechapel. Belonging to the Martineau family and located on Kingward Street, the Company secured a joint license with Tate and Lyle of the Langen cube-making process in the late nineteenth century and this delayed their demise but could not halt it altogether. Martineau’s closed in 1961.2

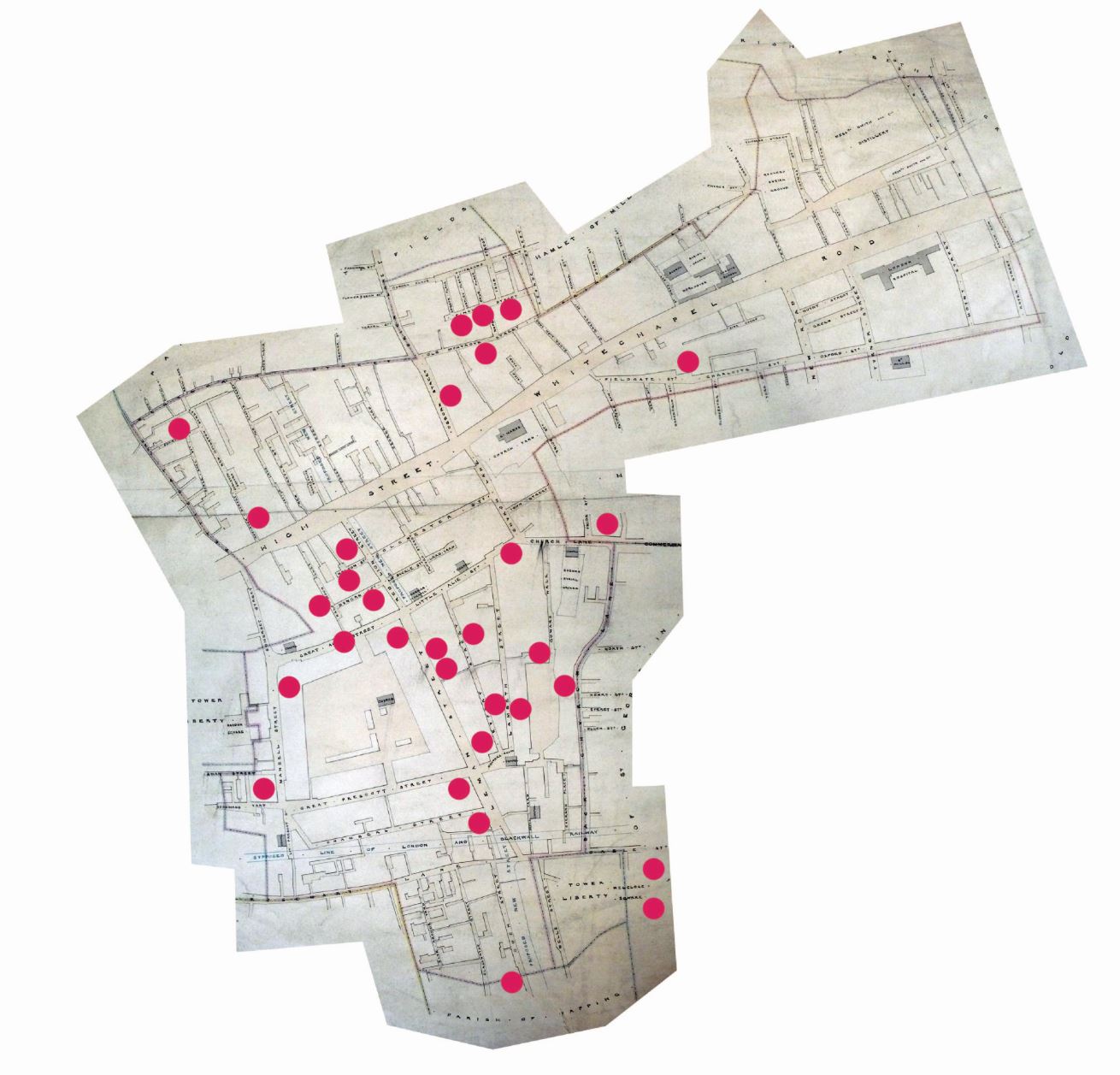

Approx. locations of Whitechapel sugarhouses, c.1840, plotted onto Grellier’s map, c.1840-5 (LMA, SC/PM/ST/01/002)

Of French Huguenot descent, the Martineau family had become one of the most important names in the London industry in the nineteenth century. Owning a number of Whitechapel refineries after their forced relocation outside the City walls in 1800, the business was divided between two Norwich-born brothers, David (1754-1840) and Peter (1755-1847). David developed a group of sugarhouses at the south end of Christian Street. Peter, on the other hand, established himself in the north-west of the parish in airy Goulston Square.

In 1775 John Fry, a merchant of Finsbury, was owner of a warehouse in the south-eastern corner of Goulston Square, formerly Cowley’s Snuff House. Significantly however, by 1806 he was also in possession of an apparently substantial sugarhouse located on the north side of present-day New Goulston Street. This was a commercial partnership with William Osborne, who had previously refined sugar on the site with James Diass in 1801. The business failed however and Fry was declared bankrupt in 1806; his assets, including the sugarhouse and its contents, were auctioned off. The seized sugarhouse was awaiting a new owner when a case against a theft of a loaf of sugar by a sugarbaker was heard at the Old Bailey. Involving three sugar bakers at the site as well as the clerk of the sugarhouse, John Bell, the incident confirmed that the refinery was gated and possessed a ‘men’s room’ – a lodging house for single male workers. The demise of Fry’s business dovetailed with the Martineau’s arrival into Whitechapel from the City. Two confiscated sites, a warehouse at nos 3-5 Goulston Street and the sugarhouse on New Goulston Street, were transferred to Peter Martineau who was quick to recognise the potential for further development at the northern site. Sometime between 1813 and 1818, Martineau constructed a brick dwelling house, counting house, new men’s room and scum house (used for producing lower grade sugar by-products) facing onto both New Goulston Street and Goulston Street. This new accommodation was located to the east of the main sugarhouse and divided from it by a gated yard. Given the flammable nature of the sugar and also the intense heat necessary for the production of it, separation of the most dangerous processes from on-site housing was typical. In 1817, Peter Martineau & Sons ‘of Goulston Street’ insured stock, utensils and the brick sugar house for £19 000 spread across five insurance companies (Sun, Eagle, Atlas, Glove, Union). The additional new buildings and their contents were insured with the Sun for £3000 one year later. This was comparable to the seven-storey premises of Severn, King and Co at Commercial Road, insured for £15 000 in 1819.3

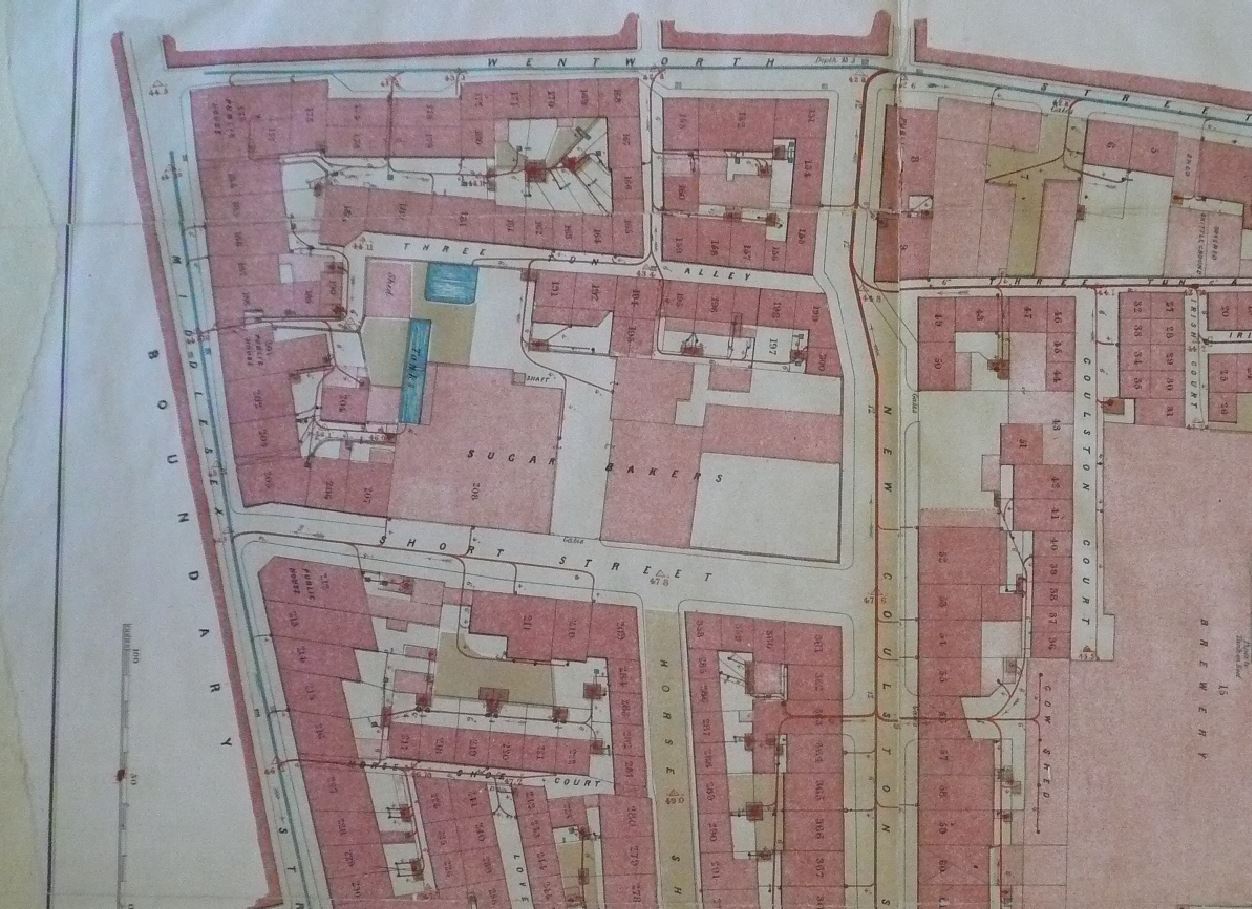

Metropolitan Sewers Plan of Goulston Street and Neighbourhood, Whitechapel, 1849 (LMA, SC/PM/ST/01/002). Site of Martineau's sugarhouse marked 'Sugar Bakers' on Short Street (later renamed New Goulston Street).

Whilst the strategy of insuring the sugarhouse with a number of companies could not prevent the outbreak of fire, it certainly appears to have limited the damage caused by at least one such incident. In 1825 it was reported that a fire destroyed nearly half of the main sugarhouse building, but that the speedy arrival of three fire engines, arriving from the three different insurers, curtailed the blaze with a plentiful supply of water. In 1847 a new phase of building work was undertaken by George Webb of Gowers Walk and modern refining pans were set in place by him later in 1855. Webb was also implicated in the construction of other local sugarhouses around this period: Elers and Morgan’s at Goodman’s Stile (1849), and Davies’ at Osborne Street (1855) and Rupert Street (1854). Overseen by Charles Furnivall, Martineau and Sons added a furnace chimney in April 1862 and by 1867 it was noted to have possessed a steam works. By 1870 Peter was dead and his firm, Peter Martineau and Sons, appears to have vacated Goulston Street. Fairrie however regarded that the business stumbled on for a further three years under Peter’s grandson Hugh and ceased only on his retirement in 1873.4

Site of former

sugarhouse today. Photo looking north-west along New Goulston Street

Site of former

sugarhouse today. Photo looking north-west along New Goulston Street

-

P. Chalmin, The Making of a Sugar Giant: Tate and Lyle, 1859-1989, edn. 1990, p.12, 14, 53-54; B. Mawer, Sugarbakers: From Sweat to Sweetness, rev. edn. 2011, p.11; G. Fairrie, The Sugar Refining Families of Great Britain, 1951, pp.24-25 ↩

-

G. Martineau, Sugar from several points of view, 1918, p.475; R. Munby, Industry and Planning in Stepney, 1951, p.66; P. Chalmin, The Making of a Sugar Giant: Tate and Lyle, 1859-1989, edn. 1990, p.54; B. Mawer, Sugarbakers: From Sweat to Sweetness, rev. edn. 2011, p.41 ↩

-

Land Tax; Bryan Mawer, Sugar Refiners and Sugarbakers Database [Online: www.mawer.clara.net]; The Times, ‘John Fry of New Goulston Street’, 18 Nov 1806; Old Bailey Proceedings, ‘John Madell, Theft’, 2 Jul 1806 [Online: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/]; LMA, CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/475/933750, CLC/B/192/F/MS11936/473/929001, CLC/B/F/001/MS11936/472/933388; B. Mawer, Sugarbakers: From Sweat to Sweetness, rev. edn. 2011, p.63; G. Dodd, Days at the Factories, 1843, pp.89–110 ↩

-

Morning Post, 7 April 1825, p.3; Evening Mail, 8 April 1825, p.4; DSRs; MBW, 11 April 1862, p.298; G. Fairrie, The Sugar Refining Families of Great Britain, 1951, p.25 ↩

Sons of Lodz synagogue

Contributed by Survey of London on July 16, 2018

A small synagogue, possibly a successor to the Newcastle Street synagogue was located in Davis Mansions, New Goulston Street, from the 1890s to the 1930s. Converted from a shop in 1895-6 by the building’s landlord, Abraham Davis, it housed the Sons of Lodz, or Lodzer Synagogue, from then until it merged with the Lubner synagogue c. 1934, the merged synagogue merging in turn with the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue after 1947.1

-

Jewish Chronicle, 8 Oct 1897, p. 27; 8 Sept 1899, p. 23: London Metropolitan Archives, District Surveyor's Returns: https://www.jewishgen.org /jcr-uk/London/EE_lublin-lodz/index.htm ↩

The Goulston Street Improvement

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 1, 2019

The topography of the area between Middlesex Street and Old Castle Street changed radically in the 1880s as a consequence of concerted slum clearances and road widenings. This owed much to the Rev. Samuel Barnett and John Liddle, the Whitechapel District Board of Works' Medical Officer of Health, who had been campaigning for improvements in living conditions since the 1840s.1

Drainage aside, little had changed in the huddled streets north of Whitechapel High Street. The Artizans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Act of 1868 (the Torrens Act) to encourage large-scale slum clearance and rebuilding had lacked the force of Torrens’ original bill, as was pointed out by an influential report of 1873 (and subsequent memorial to Parliament) by the Charity Organisation Society, with which Barnett was closely involved. This recommended that local authorities be given compulsory purchase powers in slum areas. The Society’s aim was not philanthropic and it opposed municipal house building except as a last resort. Rather it aspired to social engineering through improved housing. If the slum houses were demolished and replaced with good-quality blocks, better tenants would be drawn in and the most resilient of the poor (the ‘deserving’) would occupy the houses they had left, thus ‘levelling up’ an area. Barnett put it more starkly: ‘If the gang of thieves and idlers who inhabit this quarter could be scattered and good houses built, the boon would be immense’.2

The Artizans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875, introduced by the Home Secretary Richard Assheton Cross, aimed to remedy the shortcomings of the Torrens Act by enabling local authorities (in London, the Metropolitan Board of Works) to conduct slum clearance on a scale large enough to generate sites attractive to model dwellings companies. The thorniest issue was compensation to the slum landlord – not to give full market value was considered inequitable, selling sites below market value an unjustified imposition on ratepayers, yet selling them at full market value made them unattractive to builders. Barnett’s view was that ‘the community must be content to lose money by letting the ground at a lower rate’.3 This played out in wrangling over compensation that dragged on through arbitration and saw awards that made slum clearance onerous to the Board, and slow in the time it took to sell cleared sites.4

Whitechapel was subject early and extensively to the Cross Act, first in the Whitechapel and Limehouse Improvement Act of 1876, the implementation of which in an area south of Royal Mint Street benefited from the early involvement of the Peabody Trust, and shortly after in the Metropolis (Goulston Street and Flower and Dean Street, Whitechapel) Improvement Act of 1877, which led to a slower process. These Acts came about through representations to the MBW by Liddle, the later one in particular concerning two sites, one of about three acres, encompassing Queen’s Court off the High Street (the site of Whitechapel Gallery) and parts of Angel Alley and George Yard, running north across Wentworth Street into Spitalfields to Flower and Dean Street, and, the subject here, four and a half acres bounded by Middlesex Street and Goulston Street east and west, and Wentworth Street and the backs of High Street properties north and south.5

Fragmented ownership and displacement from both areas of more than 4,000 people, meant that assembling the sites was laborious. Amendments to the Cross Act in 1879 and 1882, reducing both the rate of compensation to slum landlords, and the proportion of displaced persons who had to be rehoused locally, speeded up clearances, much of which occurred in 1880–1, though it was not until 1884 that final acquisitions of the many crowded and insanitary courts were made. The amended legislation enabled widening of the main streets; sections of Middlesex Street, Goulston Street and Wentworth Street were widened to 40ft, and New Goulston Street to 30ft.6

The scheme proposed commercial redevelopment of the main street frontages (Middlesex Street, the eastern part of Wentworth Street, and odd plots on Commercial Street), and envisaged five-storey parallel blocks mostly end-on to New Goulston Street and the western part of Wentworth Street. Model-dwelling use for eighty years was to be stipulated. Some smaller commercial sites were built up in 1883–4, including the Bell on Middlesex Street and the Princess Alice on Commercial Street, and widened Middlesex Street was paved in granite, with York-stone pavements, by J. J. Griffiths, builder. But the core work of building blocks of model dwellings was slow to start. As Barnett bemoaned in 1884: ‘During the whole year acres of ground cleared by the Metropolitan Board of Works … have remained barren as a desert’.7 Another short-term consequence of the slow pace of demolition was, as Barnett had predicted, that slum property deteriorated as landlords saw no reason to improve condemned houses. Before 1882 local authorities were reluctant to buy and demolish as there was a requirement to rehouse occupants locally. Moreover, the scale of clearances when they finally happened and subsequent delays in selling sites were also deleterious. At the end of 1884 the Whitechapel Board of Works estimated that 12,000 had been made homeless in its district. The need for many to remain close to their places of work, or simply to stay with their friends and family, meant that overcrowding increased sharply.8

The MBW’s first sale of property scheduled for blocks of dwellings was of the largest site, fronting Wentworth Street, the north end of Goulston Street on both sides and Old Castle Street’s west side. The buyer in June 1884 was William Boutcher, of the Wentworth Dwellings Company Ltd. Boutcher was unusual as a developer of model dwellings: he was an artist and illustrator, who had travelled in 1854–5 at the behest of the British Museum to make record drawings of Nimrud for W. K. Loftus’s excavation; a some-time architectural student at the Royal Academy (and designer of, inter alia, model dairies); a crack-shot member of the Artists’ Rifles; and, in the late 1880s, the MBW’s member for Kensington. He declined to deal with T. J. Robertson, an MBW Architects’ clerk under investigation for taking bribes to secure tenders.9

Complete by the end of 1886, Wentworth Dwellings, 471 flats in all, comprised four main and largely surviving blocks of five storeys over basements, with shops on the ground floors of the Wentworth Street and Goulston Street frontages. An additional four-storey block and six single-storey workshops stood behind the eastern L. There were also washhouse blocks in the yards. Boutcher’s scheme was architecturally a cut above standard model dwellings. The stock-brick elevations were enlivened with occasional red-brick courses, gauged window heads and residually Gothic Revival composite-stone doorheads on Goulston Street. Open staircases under red-brick arches sub-divided the blocks.10

The flats varied from one to three rooms, the majority being of two. The return for Boutcher and his investors was healthy, six per cent in the 1890s, a consequence of the rents, at 6s.6d.to 10s.6d., which, as often observed, precluded the poorest class of labourers. The shops reflected Wentworth Street’s status as an adjunct to Petticoat Lane market. There was from the outset a fair representation of the rag trade (milliners, drapers, silk mercers, trimmings), but most shops housed such as fishmongers, fruiterers, grocers, butchers and tobacconists. The workshops fell to use mainly as builders’ stores.11

In February 1885 Samuel Toye bought the whole west side of Goulston Street south of New Goulston Street for the erection of model dwellings. Toye was an intermediary for James Hartnoll, a joiner turned developer and self-styled ‘architect’, with whom he had worked on at least one other scheme in Clerkenwell. Hartnoll, who died at forty-six in 1900, made a fortune in the 1880s and ’90s building model dwellings and mansion flats on ground left over from public schemes – slum clearances, railway developments and street improvements. He was undeterred by the statutory requirements and restrictive conditions that often made such sites unattractive to philanthropic societies and other developers.12 According to Hartnoll gave evidence in 1888 to the Royal Commission examining alleged irregularities at the Metropolitan Board. The MBW had declined to deal with him as they doubted his competence to build such a large scheme; this despite him having paid for the services of T. J. Robertson, the allegedly corrupt clerk. In his own words, Hartnoll was ‘exceptionally experienced in the successful planning, erection and maintenance of Model Dwellings, as well as being the largest individual owner of this class of property in London’. Brunswick Buildings, the vast scheme he built on Goulston Street in 1885–6, contributed greatly to that claim.13

Hartnoll had lived in Germany, and used German names for many of his developments. Brunswick Buildings was a continuous run of fifteen six- and seven-storey blocks that turned the corner to New Goulston Street with a further four blocks. There were also a few more blocks behind the Goulston Street range for 280 flats altogether.14 In a manner typical of Hartnoll, the development was of stock brick with stone quoins and two continuous reconstituted-stone courses stepped up as window heads, articulation like that at Hartnoll’s surviving shophouses at 52–72 Middlesex Street. Most flats were of two rooms plus a scullery, though a number had one or three rooms, all were reached by open stone stairs.

Barnett noted: ‘In the broad streets with their clean, tall dwellings it is almost impossible to recall the net of squalid courts and filthy passages which went by the name of streets. After nine years’ waiting and the delays which seem to be necessary in the action of the Metropolitan Board of Works, the improvement has been completed. Brunswick Buildings in Goulston Street and Wentworth Buildings {sic} in Wentworth Street, are inhabited.’15 Charles Booth’s researcher found the residents ‘decent working people … mainly Jews’.16 By the First World War Hartnoll Estates had disposed of Brunswick Buildings to the UK Temperance and General Provident Institution, and they were described as ‘in a pretty bad state with poor class of tenants’.17

The north side of New Goulston Street was excluded from the clearance area in the Improvement Act of 1877 on account, no doubt, of the cost of acquiring the former sugarhouse there (see above). When the site did come up for sale in 1890, with the suggestion that it might be adapted for commercial purposes, it was acquired by Abraham Davis (1857–1924), the third of the seven Davis brothers who built widely in Whitechapel, generally putting up working-class tenements. Abraham went on to have a hugely versatile career, but the building of Davis Mansions on this site, in a part of Whitechapel he had lived in as a child, was his first major solo development. It followed an established model, with five floors of flats over shops to New Goulston Street. Built in 1894–5, there were 148 flats in four contiguous blocks behind the western blocks of Wentworth Dwellings.18

Davis Mansions bore more than a passing resemblance to red-brick ‘mansion’ blocks erected by James Hartnoll on Rosebery Avenue and Gray’s Inn Road to a higher specification than Brunswick Buildings. They had similar architectural pretension, with Queen Anne details, pedimented shop fronts, high-level arcading and a modest corner tourelle, but they were not ‘mansion flats’ in the West End sense. They had a higher proportion of three-room flats than Wentworth Dwellings and Brunswick Buildings and were aimed at a class of tenant one step up. As in other Davis developments, Davis Mansions included workshops, here in the basements, to cater for local domestic industries.

Davis Mansions was notable for its almost exclusively Jewish occupancy, an apparently deliberate policy of Davis’s that provoked controversy when notices that ‘No English need apply’ were displayed to prospective tenants.19 The shops were almost exclusively in clothing-trade use throughout the buildings’ existence. One exception was a small synagogue, possibly a successor to a synagogue on Newcastle Street, converted from a shop unit by Davis in 1895–6. This was known as the Sons of Lodz, or Lodzer, Synagogue until around1934 when it closed following merger with the Lubner synagogue, which merged in turn with the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue after 1947.20

The west end of the westernmost Wentworth Dwellings block was a casualty of the Second World War, rebuilt in 1954 in Utility style with plain brick fronts and metal windows. All but the six northernmost Brunswick Buildings blocks were also damaged beyond repair after a direct hit by a V2 rocket bomb on 10 November 1944; the corner block was rebuilt in 1955. By the 1960s the remaining dwelling blocks in the area were scheduled for slum clearance by the London County Council, but work was slow to be implemented.21

Davis Mansions had been the first of the late-nineteenth-century dwellings in the Goulston Street–Wentworth Street nexus to be condemned as unfit for habitation and in 1965 the first for which a Compulsory Purchase Order was secured. Clearance was completed by the GLC in 1974, and the site was laid out as public open space for a time from 1976.22

A survey of 1972 found what remained of Brunswick Buildings beset by ‘disrepair, dampness, unsatisfactory internal arrangements, insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, inconveniently situated sanitary accommodation and water supplies and inadequate facilities for the preparation of food’.23 Compulsory Purchase Orders for Brunswick Buildings were secured in 1975–6, despite objections from the several freeholders. Interviews with tenants to assess compensation for good maintenance revealed the poor condition of the buildings and the shifting demography of Whitechapel.Alexander Solomons at Flat 264 on New Goulston Street said he had lived there for seventy-one years and that ‘the flat is rotting, the ceiling is in places wood, the windows [are] rotting’, complaints echoed by Tuta Miah at Flat 242. An unnamed tenant at Flat 233 said ‘I am only living here with great difficulties’.24 The corner block, only twenty years old, had a factory in its basement.

The last old blocks of Brunswick Buildings were duly demolished in 1981. There was less certainty about how far a redevelopment scheme should include Wentworth Dwellings. The view in Tower Hamlets Council in 1965 was that ‘the only really effective way to deal with tenement blocks is to demolish and rebuild’.25 But the issues with this for Roy Archer, the GLC’s Valuer, were cost and disruption. Wentworth Dwellings incorporated ground-floor commerce, ‘which accounts for a lot of the value of the blocks but doesn’t come under the terms of [Section III of] the [1957] Housing Act’.26 Similar exemption also applied to the two rebuilds of the 1950s, the corner block at Brunswick Buildings and the section of Wentworth Dwellings at 6–14 Wentworth Street. Rehabilitation was under contemplation by the mid-1970s, but there was fierce resistance to the idea, even within the GLC. Archer pursued the possibility and considered the commercial activity in social as well as economic terms: ‘These streets (Wentworth and Goulston) form part of the “Petticoat Lane” complex, a dedicated market area, with a vigorous barrow trade, and provide a focal point for the local community’.27 The GLC decided to acquire Wentworth Dwellings, then still in private ownership, under another clause of the Housing Act, and carried out a feasibility study with a view to rehabilitation.

In parallel, designs for replacing Brunswick Buildings, Wentworth Dwellings and Davis Mansions were prepared in 1982–3 by the GLC Architect’s Department. The scheme proposed extinguishing Goulston Street north of New Goulston Street to create a glass-roofed pedestrian market extending westwards, between blocks of low-rise flats on the site of Davis Mansions and all but the 1950s part of Wentworth Dwellings, with a further block on the Brunswick Buildings site south of New Goulston Street. Three phases were intended, to start at Brunswick Buildings and proceed clockwise to conclude east of Goulston Street. In the event only the first phase was built, in 1985, as blocks either side of New Goulston Street: Brunswick House, twenty flats to the south; and 20–27 Wentworth Dwellings, to the north, set back to allow for the intended market and finished abruptly at the flank wall of the reprieved Wentworth Dwellings. These buildings of up to four storeys are in a late-GLC neo-vernacular style, of brown brick with canted oriel windows, slate-effect hipped roofs and canted corners creating rhomboid shapes on plan. Bright-red tubular canopies over the shops were removed in 2018. At 20–27 Wentworth Dwellings single-storey shops form a podium for raised communal gardens and private terraces. Brunswick House has glazed sunrooms to the rear. In 2005 a flat was added above 21 Wentworth Dwellings, a consequence of tenants exercising their ‘right to buy’.28

By 1986 the old Wentworth Dwellings blocks were empty and boarded up, awaiting refurbishment which eventually came in 1991–2 when the name Arcadia Court was introduced; the western ranges had come to be known as Merchant House. To the rear, podiums were formed above space for market storage, with gardens on the roof and access to staircases, now lit by glass louvres. On the west side of Goulston Street new access came via a mildly Post-modern gateway to the south. A new four-storey block of eleven flats, architecturally in keeping, was built on the west side of Old Castle Street. Arcadia Court and Brunswick House were transferred to East End Homes in 2006, along with the New Holland Estate and Jacobson and Herbert Houses.29

Brunswick Buildings had survived long enough to provide a base, in a basement flat (No. 269), for the founding in 1977 by Anwara Begum and Muhammad Nurul Huq of the East End Community School, a mother-tongue supplementary school for children of Bengali heritage. This reflected concern among parents at their children’s lack of access to Bengali language and culture. In 1980, after a period in a classroom on the site of Davis Mansions, the school moved to Portakabins on the east side of Old Castle Street behind Denning Point where it remained for more than thirty years. By 2011 there were more than ninety Bengali supplementary schools in Tower Hamlets.30 In 1995 a shop at 33–35 Goulston Street, opened as the Brunswick and Wentworth Community Centre, a registered charity offering housing, health and welfare advice, a children’s supplementary evening school, and IT training. The area in front has been enclosed since 2001 with low railed walls with bench seats. Around 2011 the East End Community School transferred here from its Old Castle Street Portakabins. In 2019 it is a branch of Tanzeel, a chain of Islamic schools founded in 2007, providing after-school courses in Qu’ranic studies and Arabic.31

<div> <div> <div>

</div> </div> </div>

-

East London Observer, 4 Aug 1883, p.3; 27 Oct 1888, p.4 ↩

-

Henrietta Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life, Works and Friends, 1918, vol.1, p.129: Anthony S. Wohl, The Eternal Slum: Housing and Social Policy in Victorian London, 1977, edn 2009, pp.84–95: Gareth Stedman Jones, Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship Between the Classes in Victorian London, 1971, edn 2013, pp.197–9 ↩

-

Barnett, p.130 ↩

-

Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes (MBW Mins), 1878–84, passim: Wohl, pp.93–5,100–1 ↩

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), MBW/1838/5 ↩

-

MBW Mins, 1877–84, passim: ed. C. J. Stewart, The Housing Question in London, Being an Account of the Housing Work done by the Metropolitan Board of Works and the London County Council between … 1855 and 1900, 1900, pp.118–20: John Nelson Tarn, Five Per Cent Philanthropy: An Account of Housing in Urban Areas between 1840 and 1914, 1973, pp.87–8 ↩

-

Barnett, p.137: LMA, MBW/2635/20 ↩

-

The Builder, 27 Dec 1884, p.878: Report from the Select Committee on Artizans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings, 1882, pp.161–8: Wohl, p.105 ↩

-

MBW Mins, 9 Feb, 20 June and 27 June 1884, pp.285,1012,1030: Civil Engineer’s and Architect’s Journal, August 1847, pp.261–2: The Builder, 15 April 1848, p.190; 14 Feb 1891, p.126: Building News, 3 Oct 1862, pp.256–8; 12 April 1878, p.366:Volunteer Service Gazette and Military Despatch, 22 May 1880, p.16; 28 July 1883, p.16: West London Observer, 17 July 1886, p.3: The Graphic, 12 May 1888, p.4: Warminster and Westbury Journal, 23 June 1888, p.7:V&A, SP.109; E.3524–1909: British Museum, 2007,6024.21: H. V. Hilprecht, The Resurrection of Assyria and Babylonia, 1904, p.129: Caroline Dakers, The Holland Park Circle, 1999, p.183 ↩

-

LMA, District Surveyors Returns (DSR): Barnett, p.138: The National Archives (TNA), IR58/82818/3588–3606; IR58/82819/3601–37, 3696–3707, 3788–92; IR58/82820/3701–3800 ↩

-

Jewish Chronicle (JC), 14 Nov 1884, p.14; 27 Feb 1885, p.8: St James’s Gazette, 26 May 1897, p.15: Post Office Directories (POD): Tarn, pp.87–8 ↩

-

MBW Mins, 24 April 1885, p.726: ed. Stewart, pp.122–3: Isobel Watson, ‘The Buildings of James Hartnoll’, Newsletter of the Camden History Society, no.58, March 1980: Isobel Watson, ‘Five Per Cent Philanthropy: Model Houses for the Working Classes in Victorian Camden’, Camden History Review, no.9, 1981, pp.4–9: information kindly supplied by Christopher Hartnoll: ed. Philip Temple,Survey of London, vol.47: Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, 2008, p.120 ↩

-

LMA, LCC/MIN/2815, 7 July 1890: Kentish Independent, 16 June 1888, p.2 ↩

-

DSR: TNA, IR58/84810–12 ↩

-

Barnett, p.138 ↩

-

London School of Economics, British Library of Political and Economic Science (LSE), BOOTH B/10 ↩

-

TNA, IR58/84810/2709–857; IR58/84812/2901,2929–72 ↩

-

DSR: London Evening Standard, 9 June 1890, p.12: Morning Post, 17 July 1891, p.8: TNA, IR58/84813/3001–9, 3017–72: Isobel Watson, ‘Rebuilding London: Abraham Davis and his Brothers,1881–1924’, London Journal, vol.29/1, 2004, pp.62–84: Isobel Watson, ‘Work, Wait, Win: The Davis Brothers of Whitechapel and their London Buildings’, East London History Society Newsletter, no.2/11, Spring 2005, pp.17–19 ↩

-

LSE, Booth Archive, B/351, p.113 ↩

-

POD: JC, 8 Oct 1897, p.27; 8 Sept 1899, p.23: DSR: Richard Mudie- Smith, The Religious Life of London, 1904, p.265: <u>www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/London/EE_lublin- lodz/index.htm</u> ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), L/THL/D/1/3/1: J. B. Cullingworth, ‘Urban Renewal’, Town and Country Planning in England and Wales, 1971, pp.262–88 (p.269): Tower Hamlets planning applications online (THP) ↩

-

LMA, GLC/MA/SC/003/2742; SC/PHL/01/390/X74/914; SC/PHL/01/394/X74/511; SC/PHL/01/394/75/35/76/11 ↩

-

LMA, GLC/MA/SC/003/2740–3 ↩

-

LMA, GLC/MA/SC/003/2740; GLC/MA/SC/003/2742 ↩

-

THLHLA, L/THL/A/11/1/1: THP ↩

-

LMA, GLC/MA/SC/003/2742 ↩

-

Ibid: Jim Yelling, ‘The incidence of slum clearance in England and Wales, 1955–85', Urban History, vol.27/2, August 2000, pp.234–54 ↩

-

LMA, GLC/AR/G/10/8: THP ↩

-

information and photographs kindly supplied by Lesley Love and Gary Hutton: THP ↩

-

M. Huque, The Story of East End Community School, 2009: Ansar Ahmed Ullah and John Eversley, Bengalis in London’s East End, London, 2010, p.68 ↩

-

THP: THLHLA, LC13812: democracy.towerhamlets.gov.uk/mgConvert2PDF.aspx?ID=3073: www.tanzeel.co.uk/aboutus.html ↩

Wentworth Dwellings, New Goulston Street from the south-east in 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Goulston Street Improvement, plans of sites taken for development in 1877 (drawing by Helen Jones)

Contributed by Survey of London

Goulston Street Improvement, early proposed layout (drawing by Helen Jones)

Contributed by Survey of London

Goulston Street Improvement, redevelopment as completed by 1894 (drawing by Helen Jones)

Contributed by Survey of London

New Goulston Street and 48-105 Davis Mansions, c. 1960 (see archive.HistoricEngland.org.uk)

Contributed by Aileen Reid