Sunley House

1976 brick-built flats on site of George Yard Buildings, later Balliol House/Charles Booth House. Demolished for Toynbee redevelopment 2016

George Yard Buildings and St George's House

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 14, 2018

George Yard Buildings (later called Balliol House and later still Charles Booth House), which was demolished for the building of Sunley House, was one of the earliest blocks of model dwellings built in Whitechapel in response to the 1875 Artizans and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act. The Act, instituted by the Home Secretary R.A. Cross, who Samuel Barnett of Toynbee Hall had previously shown around the Whitechapel slums, and based partly on a housing report by the Charity Organisation Society, of which Barnett was a founder, had allowed for compulsory purchase of slum property by the local authorities. But designation of an area for slum clearance could, as Lord Shaftesbury predicted, have deleterious consequences, a view with which Barnett concurred: ‘The expectancy of early removal makes landlords unwilling to spend money on necessary repairs, and tenants unwell, by leaving, to miss the chance of compensation’.1 One answer was that taken by Octavia Hill from the mid-1860s of improving and running existing property. The Barnetts were involved in this in Whitechapel immediately, aided and abetted by Whitechapel’s Medical Officer of Health, John Liddle, who until the Cross Act, could only highlight the squalor of courts where ‘each inhabitant has only four yards of space, and from which fever is never absent’, and condemn them as unfit for habitation.2

With Octavia Hill’s encouragement and half the cost from Edward Bond, later chair of the Technical Education Board and later developer of Katharine Buildings in Cartwright Street, they had acquired the surviving slum houses in New Court, which led off George Yard (Gunthorpe Street), mainly occupied by ‘women living shameful lives from whom large rents were demanded by a disreputable man’, offering the tenants ‘a chance to reform’ before being evicted, and renovated the remaining housing pending redevelopment.3 Similar low-key schemes of renovation were pursued in 1875-6 in 3 and 4 Angel Alley and 92-94 Wentworth Street (near the west corner of George Yard, both on the site of the Dellow Centre), also paid for by Bond and 1 and 2 and 5 to 8 inclusive Angel Alley and 75-83 Wentworth Street (east of Angel Alley, on the site of Universal House), paid for by the Earl of Pembroke.

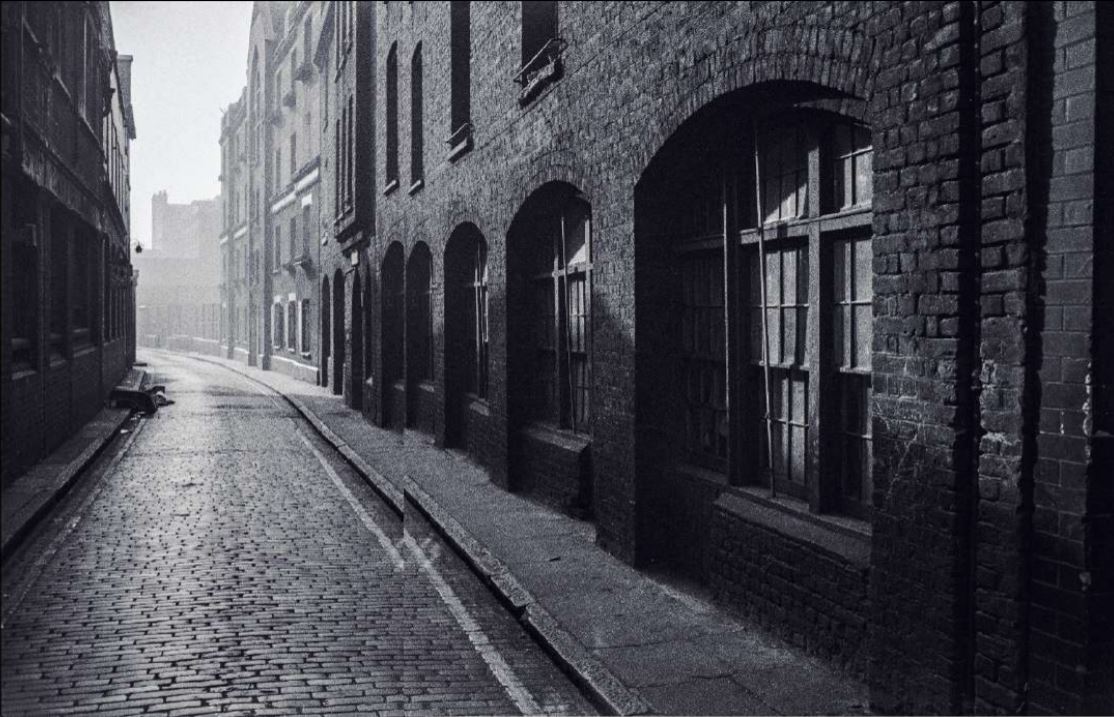

The Barnetts’ friend and Charity Organisation Society associate, Augustus George Crowder (1843-1924), executed a more ambitious scheme in building George Yard Buildings, a block of model dwellings on the site of a timber yard at the northwest end, adjoining west the slum-like New Court.4 George Yard Buildings was a four-storey block of forty-eight flats, in a simple, muscular red-brick Gothic, with ground-floor shops, and a bold rubbed-brick two-centred arched main entrance through to staircase and rear access balconies and a large single-storey annexe for a club-room and mothers’ meetings. All these endeavours, supervised by ‘lady rent collectors’ on Octavia Hill lines, sought to solve the apparently insoluble problem of how to house the poorest class. Rents were kept low: rates for single-room flats ranged from 1s 6d to 3s 6d when the lowest rate that the Peabody Trust could achieve was 3s. Such a rate, however, was unlikely to make the model widely replicable as it was hard to achieve the five per cent return sought by investors, and the Olivia Hill model, with its intense supervision of behaviour and requirement that rent be paid on time in advance, was both labour-intensive and unsuited to casual labourers, who made up a high proportion of the poor in Whitechapel.5

It was also no solution to the issue of overcrowding: all but three of the George Yard Buildings flats were single-room (which, given that towards the end of its existence the block accommodated 200 individuals, suggests that overcrowding was still an issue), and Barnett admitted, in evidence to the 1882 Committee on Artisans’ Dwellings, apropos the houses in Wentworth Street he managed for Lord Pembroke, that there were seven living in one room: ‘It is not what one wants; it is better than living, as they did before, on a hovel’.6 C Not surprisingly, perhaps, those, such as A.G. Crowder, who had taken on the task of housing the poorest, were becoming jaded with the enterprise: ‘For several years the practice was not to disturb any tenant who paid his rent, with the result that I became literally ashamed with the state of my property though managed by experienced and judicious ladies, visiting weekly. The vicious, dirty and destructive habits of the lowest strata have obliged me at last to decline them as tenants’. He also saw the necessity of allowing single-room occupancy by families if the very poor were to be accommodated: ‘It is astonishing what comparative decency and comfort is attainable in one room when the wife is capable and cleanly’.7

In 1889 George Yard Buildings was closed. The reason given by Crowder was that there was now ‘ample opportunity in neighbouring buildings’ (the vast blocks in Goulston Street and the East End Dwellings Company’s blocks north of Wentworth Street) for the tenants to find better accommodation. Unlets had amounted to £60 a year though a further factor may have been the brutal murder of a woman named Martha Tabram or Turner in August 1888, possibly the first of Jack the Ripper’s victims, whose body was found on one of the landings at George Yard Buildings.

In 1889-90 George Yard Buildings was converted into Balliol House a student hostel along the same lines as Wadham House, the former mothers’ meeting room altered as a common room in 1891.8 Together, the buildings formed a sort of secondary quad, with the tennis court, behind Toynbee Hall.

Some of Barnett’s aims never came to be fulfilled. The occupancy of Balliol and Wadham Houses was increasingly middle-class – according to William Beveridge, who lived there from 1903 to 1906, ‘the artisan is conspicuous by his absence’ - and the commitment to ‘the goal of connection’ was limited to fewer and fewer, as students preferred to commute from more congenial areas of London. Balliol House closed in 1913 and Wadham House a few years later.9 In 1922 Balliol House was converted into offices for the Charity Organisation Society and various children's charities, and renamed Charles Booth House, after the great social investigator.10 It was demolished in 1973 for the building of Sunley House.

St George's House

A similar four-storey red brick block of forty model dwellings, but one which lasted longer, was St George’s House, built adjoining George Yard Buildings to the south by J. Morter, builder of Forest Lane, Stratford, for Barnett’s friend G. Murray Smith, and his family in 1883. It was still offering accommodation from only 3s 6d per week just before the First World War.11 After the war, under the London County Council, it was scheduled for clearance as substandard, though it was only c. 1968, under the new London-wide authority, the Greater London Council, that tenants were rehoused in the New Holland Estate on Commercial Street. The building survived a few more years and, encouraged by the Warden of Toynbee Hall, Walter Birmingham, St George’s House housed various charities and campaigning groups, including the Community Service Volunteers and the Commonwealth Students’ Children’s Society, until it was also demolished in 1973 for the building of Sunley House.12

-

Henrietta Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life, Work, and Friends, 2 vols, London, 1918, vol. 1, pp. 129-30 (Canon Barnett) ↩

-

Canon Barnett, vol. 1, p. 129 ↩

-

Canon Barnett, vol. 1, p. 141: Land Tax returns ↩

-

Ancestry: Canon Barnett, vol. 1, pp. 131-2 ↩

-

Gareth Stedman Jones, Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship Between Classes in Victorian Society, 2013, pp. 181-96: Dwellings of the Poor: Report of the Dwellings Committee of the Charity Organisation Society, 1881, pp. 72-3 ↩

-

Charles Forster Hayward, Dwellings of the Poor, London 1877, p. 38: T. L. Worthington, The Housing of the Poor in London: Lecture Delivered at Essex Hall… November 18th, 1889, London 1890, p. 19: Stedman Jones, op. cit, p. 195 ↩

-

Pall Mall Gazette, 1 Nov 1883, p. 11 ↩

-

Asa Briggs and Anne Macartney, Toynbee Hall: The First Hundred Years, London 1984, pp. 30, 49-50, 54: DSR: Pall Mall Gazette, 17 Jan 1890, p. 6: Standish Meacham, Toynbee Hall and Social Reform, 1880-1914, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 48-9 ↩

-

Meacham, op. cit., pp. 122-3: Briggs and Macartney, op. cit., pp. 49-50 ↩

-

Post Office Directories ↩

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), Dictrict Surveyors's Returns (DSR): The National Archives (TNA), IR58/84795/1260-99: East London Observer (ELO), 5 Jan 1884, p. 8; 21 April 1888, p. 3 ↩

-

Briggs and Macartney, op. cit., pp. 163-4: Tower Hamlets planning applications online: LMA, GLC/MA/SC/02/327: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, L/THL/D/1/3/1 ↩

Sunley House

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 14, 2018

Sunley House, a red brick three- and four-storey block, was opened in 1976 on the site of Charles Booth House and St George’s House (see below). It was part of a scheme of redevelopment by Toynbee Hall, which included Attlee House on Wentworth Street, opened in 1971, and was in a similarly ‘respectful but dull’ manner, also by David Maney & Partners, architects. Its deep north section linked via a staircase tower to a shallow white-tiled lower office block behind the Toynbee Theatre. Sunley House incorporated a vehicle entry through to Toynbee Hall, a goods lift, a basement car park, eighteen flats for the elderly, and the Special Families Centre for the Mentally Handicapped, consisting of an office, and two activities room of varying sizes.1 It was demolished in 2016 for the comprehensive Toynbee Hall and London Square redevelopment, and a block of flats named 'Broadway' is currently (December 2018) being built on the site.

-

Tower Hamlets planning applications online: Asa Briggs and Anne Macartney, Toynbee Hall: The First Hundred Years, London 1984, p. 171: Bridget Cherry, Charles O’Brien, Nikolaus Pevsner, eds. The Buildings of England: London 5 East, London 2005, p.398: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, L/THL/D/1/3/1 ↩

George Yard Buildings

Contributed by amymilnesmith on July 17, 2016

After a round of slum clearances, a model lodging house was built around 1875 in George Yard on the site of New Court and a former timber yard. It was located just before the western corner of George Yard and Wentworth St.

In 1890, the dwellings were converted to lodging for the students living and working at the Toynbee Hall settlement. It was first renamed Balliol House and then Charles Booth House.

George Yard Buildings were demolished in January 1973 along with neighbouring St. George's House, both being replaced by Sunley House, itself under demolition in November 2016 as part of the Toynbee Hall estate redevelopment.

The Barnetts, Toynbee and Balliol House

Contributed by Survey of London on April 17, 2018

East End historian and guide David Charnick on the work of the Barnetts.

Well, this site here, currently demolished, was, as you say occupied by some red-brick buildings but before then, this is where Balliol House stood which used to be George Yard dwellings. We just passed the Canon Barnett School. Samuel Barnett, with his wife Henrietta, they were the force behind the establishment of Toynbee Hall in 1884. He came to the area in 1872 to become vicar of St. Jude's Church which has long since been demolished, that's approximately across the street from where we're standing now, so just to the south of Toynbee Hall.

Samuel Barnett was a major figure in the area in terms of philanthropy and relief. One of his areas was housing. He was one of the people behind the East End Dwellings Company whose first block of tenements was in Aldgate. This was what was called model dwellings or we would call social housing. The house that used to occupy the space here was originally George Yard Dwellings which was philanthropic housing.

[There was a] church was just across the way from where we're standing now so just to the south of Toynbee Hall. Oxford University was behind Toynbee Hall but a lot of the work was provided by volunteers. These were, as I mentioned, students who would take a year after their study. They would come here and stay for the year. They would engage themselves in outreach locally through what we would call adult education. They [organised] free courses for local people to do, and a variety of things.

The outreach was provided here by volunteers as I say, and they were students of Oxford University and therefore able to offer a variety of teaching and perhaps most interestingly, they had groups here that they would take on visits to overseas. There was a basket maker from Spitalfields who was on one of these trips to Italy, and he ended up being Cambridge University's first professor of Italian which is quite a leap forward from being a basket maker. There was a huge impact locally from Toynbee Hall.

Oxford University were behind it, yes, but there would have been various sources of revenue. Philanthropists in Victorian times, many of them had limited means. They may have had some means but largely limited. Samuel Barnett himself, he was just a Church of England vicar so he had no particular wealth behind him. Just a social vision as indeed did his wife Henrietta, in fact they met at a birthday party for Octavia Hill who was herself a major philanthropist and was behind a scheme for model dwellings or they say social housing as we would call it now.

David Charnick (www.charnowalks.co.uk) was speaking to Shahed Saleem on 23.02.18. The text has been edited for print.

Amateur film about George Yard Buildings and its Jack the Ripper connection

This atmospheric (if rather shaky) amateur footage by a Jack the Ripper tour guide, takes us from Whitechapel High Street, showing a number of buildings altered or demolished since it was shot in 2008, through the arch at 88 Whitechapel High Street and down the full length of Gunthorpe Street.

Contributed by Aileen Reid on Sept. 12, 2016