Nigel Taylor, the Tower Bell Foundry Manager at the time of its closure, recounts its working life

Contributed by Nigel Taylor on May 30, 2019

My name is Nigel Taylor. I was born in Hampstead. I'm from London although my family is from Warwick. We moved out to Harrow Weald when I was fairly small, and we lived there until I was six. After that, we moved up to Oxfordshire, and that's where I think things started to happen. Because when I was a schoolboy, a friend of mine said, "The bells are being taken out." They hadn't been rung for some years at Chinnor in Oxfordshire, and they were rehung. As a result of that, we both went and learned to ring.

My paternal family comes from Warwick. I used to listen to the bells at St. Mary's, and St. Nicholas Warwick ringing when we were staying there at weekends. I already had an interest in bells before I even learned to ring.

Once I learned to ring, I would never really look back. I used to cycle all over the Oxfordshire countryside. I used to knock at vicars’ doors and ask for the key to go on up to the tower and look at the bells, which in those days, of course, was not an issue. They just said, "Well, it was at your own risk", and that was it. I used to scramble around all these belfries making sketches and notes and so on. Then, of course, eventually, I decided that I would try the bell industry.

I applied for and was accepted in two different posts in the civil service. That's always what I think I thought I was going to do and certainly what my father thought I was going to do. I joined the Bell Foundry on the basis that I would join the civil service if I did not like it [in 1976 aged 18 years] and 40 years later I left it.

Because my interest went beyond bell ringing – I'd already become a well- established bell ringer, but because of my interest in the history of bells and the bell frames and bell fittings, I think it was quite natural that I would say to myself, "I ought to try the bell industry." Because I was especially interested in tuning, the tuning of bells which is a scientific art, I opted to aim at tuning bells. Eventually, that's exactly what I did. I spent some years when I joined the foundry in the moulding shop making bells. Then I started tuning, and then eventually, when the head moulder retired, I took over his job as well, and I did all the inscriptions.

I used to inscribe all the damp clay moulds with the inscriptions as required for clients and decorative friezes. Because I very much liked decorative borders, I used them far more extensively than they had been used before.

Living in Oxfordshire in those days when commuting wasn't really practical; it was a long journey to work, so I moved back into London. I lived in Stamford Hill and then Islington and Rotherhithe, and finally, Bow until I got married. When I got married, I bought a house in Essex.

I started off as a moulding shop labourer. I made up the loam bricks that are used for packing out the coats or the flasks. I made up the loam. I did all general duties, I suppose. Then I started building moulds as well. To start with, I think I was building cores, the inner moulds, then I started doing the outer moulds. Then, of course, at that point, I moved into the tuning shop and started learning how to tune. I spent a long time tuning, in fact from 1985 until the Foundry closed.

Then when the head moulder retired in 2003, I started doing all the inscriptions as well. As a result, I became the tower bell production manager because I oversaw the entire production of tower bells from start to finish. Not the fittings, but the bells themselves. Making the moulds, making the moulding templates for making the moulds, casting the bells, and tuning them.

When I joined the foundry, [the number of staff] was certainly in the high 30s. Over the years, partly because we improved our mechanization, we bought more modern machines, we required fewer people. Of course, in the last few years, as the foundry began to dwindle, I think we were down to about 25 in total including all the other staff.

I was sent on some most useful courses about moulding. They were mainly about moulding sands and scrap reduction and all this sort of thing. Quite interesting courses. Most of training of staff was in-house because loam moulding is very rare nowadays. It used to be widely used in iron founding, [but] there’s now only the Loughborough Foundry in England that uses loam moulding.

It was all in-house and the same with the tuning. The tuning is a very specialized thing. There's no college course for it. A piano tuning course wouldn't really teach you anything about bell tuning. I learned to tune under the auspices of a chap called Wally who used to work for Gillett & Johnston. They were a large bell foundry in Croydon, and they were extremely active from about 1910 to 1952/53 when their activities went into sharp decline and they closed.

He'd joined the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. He brought his knowledge from Gillett & Johnston. I had the advantage of having their knowledge of tuning and Whitechapel's knowledge on tuning, which was actually quite useful.

The process of bell making

Well, it begins with the customer's purse and the size of the tower. That's the first things, so let's do a simple one. They have a small turret, the aperture is let's say, 24 inches wide, so we're looking at a bell of about 22 inches in diameter because we would always talk in inches and hundredweights. We would then quote a price for the bell and its fittings. We would almost certainly have a 22-inch gauge to make the bell with, and if we didn't, we could design and make one. We would cut it out of plywood or order an amount of steel or stainless steel if we knew it was going to be a gauge that we were going to be using again and again.

Having produced the template and attached to it was a vertical post. A central post. We inverted that into an iron flask. The flask looked rather like a bell, and it has lots of vent holes in it.

You built the outer mould first and you used the loam bricks, which was simply dried. It's loam that's formed into moulds, just for flat brickwork effectively, dried in the drying oven, and then you lined the flask with that. Applied layers of loam until you struck up the mould, which is the effect you will get - that nice smooth finish. Then you dress it with graphite and sleeking tools to get a nice smooth finish. Stamped in all the lettering while the mould was still damp, and any decoration that you fancied putting in. Then you stoved that mould and used the inner profile of that template you made to make the core.

On both the outer and inner mould there was a step that corresponds to the outside and the inside step. When we lowered the outer mould over the inner mould, these two steps met, and you just rub the two moulds gently together. You used to just rub the outer mould from side to side a few times to form a seal, because you don't want the molten metal leaking out the bottom. Then you formed a pouring basin at the top of the mould, poured in the metal, and then the next day or two, you'd open it up from there. There was your bell.

We made bells in batches. We'd make six, seven, eight bells at a time. Generally for smaller bells, three weeks – a three week cycle. You could just about do a bell in a week and a half. You could make the bell quickly enough. It's the drying time, because loam needs a lot of drying. You couldn't really make a small bell in much under a week and a half.

[Bells were cast in] high tin bronze. It's nominally 80% copper and 20% tin, but in practice, it tended to be more tin, which was 22/23% tin. Quite often on a Friday, we would do one melt at about midday and another one about half- past three in the afternoon. Each melt would be perhaps a ton each. You set the moulds in two rows on the floor. You cast one side in the morning, one side in the afternoon. We would invite visitors associated with the bells being cast. We had a maximum of twelve, donors and people interested in the project would come along and witness their bells being poured.

Famous bells

I joined Whitechapel several years after Westminster Abbey’s bells were cast, but was involved in the making of St. Martin-in-the-Fields and Canterbury Cathedral. We made 58 bells for the Riverside carillon in New York.

Big Ben is the famous one….it's our epitome because the people say, "You must be very proud of it." I say, "Well, no, actually. It's a typical product to me of its time, it's a Victorian bell. It's the wrong shape. It has errant partials. It doesn't sound very nice, it's just famous." Back in the 1920s, Gillett & Johnston's proprietor, Cyril Johnston, who was a very much go ahead modern businessman, tried desperately hard in the 1920’s to get the authorities to recast it because, I think, once it started being broadcast on the radio, it's a sound that's known all over the world.

Once you reached that stage, there was no question of recasting though because it's become so famous, but up to that point it could've been, and he tried hard to have all five bells (Big Ben and the four quarter bells) recast because he said, "It's tonally very deficient." It never was even before the surface crack appeared soon after the bell was hung. Now, we have this enormous great gong that clangs away every hour, but it's world famous. It's almost the voice of England.

Working conditions

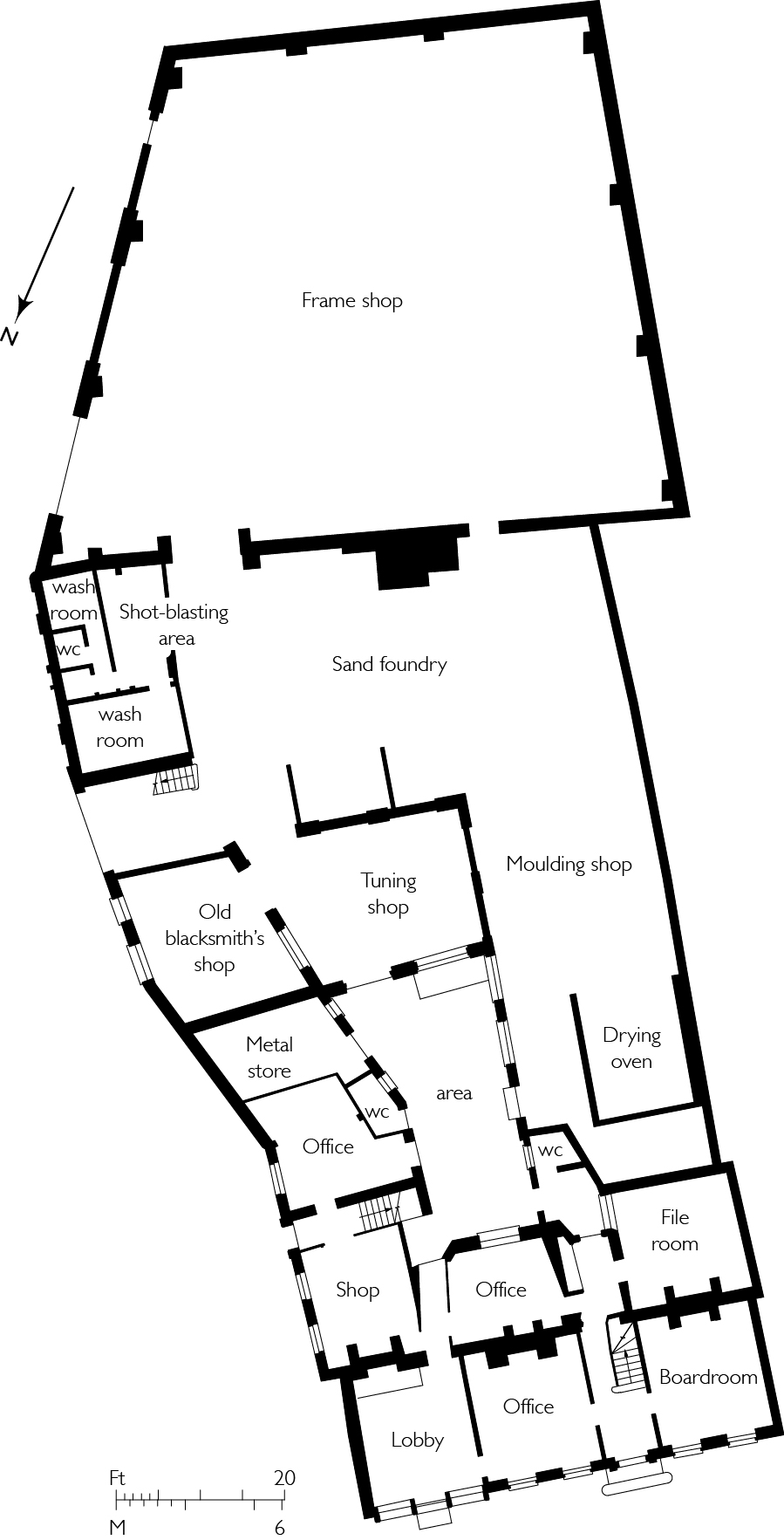

I was in the front part of the building. There's a long but narrow shop, and that is the moulding shop and the drying oven at the front. That's, obviously, where I spent quite some time. Adjacent to that was the sand foundry where they made all the small bells, the handbells, the clock bells, the little bells that they sell within the shop. It was equipped with a 60kgs capacity, oil-fired furnace.

The large tuning machine was situated in the sand foundry which wasn't ideal because it meant that the large tuning machine was adjacent to the furnace, so when we were tuning bells if the furnace was running, you couldn't test them. You just have to wait for the furnace to be turned off or idled. That wasn't ideal; in an ideal world, you always put your tuning shop completely on one side of the building and in a fairly soundproofed environment.

Once you've made the bells, you just roll them up through the sound foundry. They'd either go straight around the corner to the tuning shop, for the larger bells had cord holes, so they already have a centre hole cast in the bell. The smaller bells went out to the back foundry and they'd drill a centre hole. We used to machine the heads flat for the belt, then turn them over and invert on the vertical boring machine to start tuning.

I spent most of my time either in the moulding shop or in the tuning shop and not very much time out in the back foundry except some measuring of bells and things like that.

My official title was Tower Bell Production Manager but you could say, Master Founder.

[I managed the process of] the making of the bells themselves. Once you finish tuning the bells, they went to the back foundry where they made all the fittings and trial assembled all the frames, the fittings, and the bells. That wasn't my domain; I sent a tuned bell, together with all the dimensions required for making some of the fittings, such as the clappers and clapper staples.

History of the Bell Foundry and the Hughes family

It's had quite an interesting history. It traces itself back to Chamberlain who's in Aldgate around 1420. There are still a few of his bells extant. Next year, had the foundry existed, it could've been in effect celebrating 600 years of bell founding in this area. The Reformation, of course – there was a break. There were clearly not many if any bells being made during the Reformation. I think some of the bell founders in England just cast guns instead because it was quite lucrative and it kept them in business. There are cannons still extant that were cast by Robert Mot when he was at Whitechapel in the late 16th century.

By 1568, 1570, the foundry was up and running again in Whitechapel High Street on the north side of the road. It remained there until 1738 when it moved to the site where it was until two years ago. It is certain that there was an overlap where there were some reduction on both sides in as far as they were gradually moving all the equipment from the old foundry which I think was in – must be in Essex Road, yes, it might have been Essex Road – whilst it was being moved from the old site into the Whitechapel Road site. It must've been over a period perhaps of two years; perhaps in 1736–1738. After that, it remained on that site until 2017.

[The Hughes family go] back to 1884, ... when Arthur Hughes took on the role as general manager. Then, in 1904, he bought the company from Robert Stainbank's widow. There is still documentary evidence to that effect, before he became the owner of the business. Arthur had three sons: Albert, Leonard, and Robert. Eventually, Leonard and Robert disappeared off the scene and left Albert alone to run the business. Albert had two sons, that was William and Douglas. There was a daughter, Kathleen. She wasn't actually involved in the business but William and Douglas were.

Then, after the war, they joined their father in the business. I think, William, in 1945 and Douglas, about five years later. Albert died in 1964, William died in 1993 and Douglas in 1997. William had two children – that was Alan and his daughter, Margaret. Alan joined the business in the 1970s. He became effectively the owner until about 1997/98 when his wife Kathryn joined the business as a director.

[Alan Hughes] had been there for ten years. In a sense, he and I, we operated – in a sense of moving the foundry forward because he was already up and running and ..., by the 1970s he was obviously having some influence on what was done. Then I came in on the scene….

I think from day one, I was making suggestions. I used to say things like, "Why do you do it like this?" Typically, the staff said, "Well, we've always done it that way." I said, "Why?" "Well we always have." "Yes, but where is the logic? Why? Why do it like this?" They didn't know. They just did it because that's how they've been taught. It was I who used to question everything which must've driven them nuts. I said, "Well, I think, this idea is better. Let's do this." Eventually, I was able to implement some of my ideas and most of them were very successful, whilst some of them weren't!

We moved the foundry forward. Technically, it got better and better. The product improved. I look at jobs at Whitechapel in the 1950s and 1960s and they're fine but certainly, by the 1980s and 1990s, we were producing bell installations which were of higher quality.

People of the foundry

The foundry has its fair share of memorable characters. There were people to whom it was just a job. They came and went, some of them might only stay weeks, months, perhaps a few years. It was just a job. There were staff members from the bell ringing fraternity. There were always people at the foundry who could ring or would learn to ring subsequently if they took – really became interested in the subject.

We did have some interesting people. One of the most notable ones was Bill Theobald. He was a bell hanger. He joined the foundry, I think in 1947/48. He died in 1992. He's commemorated at a nearby pub in Spitalfields. I think there's a photograph of him there because he was a regular visitor there at lunchtimes. He used to go to the pub almost daily and have his lunch. He was a larger than life character. He was quite merciless with people. He would torment people to the point where I'm amazed actually he survived, but that's just the way he was, so he was a notable character.

Most other people sort of blended in. We had a blacksmith called Peter Trick. He now makes decorative ironwork, pokers, bird tables, and things like that, so he's gone off and formed his own business. There were quite a number of interesting characters. It's Bill Theobald, the one I tend to think of as the most extraordinary.

Other foundries

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were quite a number of bell founders still left. Whitechapel's big rival was Warners, and Warners, in fact, made the first Big Ben and they also made the four quarter bells. But, the first Big Ben cracked, and they broke the terms and conditions of recasting it. Because they thought at that stage nobody else would take on the job, they demanded a much higher price to recast the bell, and they lost the contract to Whitechapel. After that, they were bitter rivals.

Warners had a foundry at Cripplegate in the Barbican, but the Spelman Street foundry was a five-minute walk from the Whitechapel foundry. There was some movement of staff between the two companies, but they were the big rivals. Then there was Gillett & Johnston, the big foundry in Croydon that built more carillons, sets of bells hung to play tunes than any other foundry. Then there was Llewellyn’s and James of Bristol, Bond of Burford, Barwell’s of Birmingham and there was Blews of Birmingham, although in fact they had already closed by 1900. Carr’s of Smethwick ceased bellfounding in the 1920s, Bowell of Ipswich closed in 1939/40.

Certainly by the beginning of the Second World War, Bowell and Bond were just about disappearing. All the other firms had stopped founding bells except Gillett & Johnston, John Taylor and Company in Loughborough, who still exist, and the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. After the war, Gillett & Johnston closed in 1957. There was a big sort of upheaval with management because although the firm made money, it never really made enough to satisfy its creditors. It declined sharply and closed, so that then left Taylor's and Whitechapel.

In the late 1970s, Taylor's was a family business, and the last generation, Paul Taylor started to make overtures and said, "Well, what happens once I have gone?" They formed a new company, and that company kept going and then amalgamated with a bell hanging company, and then it closed in 2009 but reopened because a group of bell ringers and other interested parties financed the business and reopened it and it's still thriving today.

It was the Whitechapel Bell Foundry which was Mears & Stainbank, which became a limited company in about 1968 or 69, Whitechapel Bell Foundry Limited. Then, of course, it traded up until 2017.

Rate of production

In its day, certainly back in the 90s and early part of this decade we would make typically up to a hundred bells per year. I think by about – certainly 2008 or 2009 was a very busy period because I think we produced seven completely new rings of bells in the space of just over a year, which was almost unheard of in the family's history since the 19th century. So that was a very busy period, and of course, that was the period where Taylors [John Taylor and Company of Loughborough] previous business closed, and they've reopened.

Taylors amalgamated with a bell hanging company which already had orders on its order book. It started off with work. Then, I think it began to struggle a bit partly because after the 2010 election there were spending cuts. What happens in the bell industry is it lags behind everything else. So, for instance, back in 1930–31, during the Great Depression, all the bell factories were busy because bell projects tend to be long term projects, so if you get hit at all it happens two or three years down the line.

But, back in the '30s, there was so much work, it didn't affect the industry really at all, but this time it did. By about 2013, there was a drop off in bell production, both for Taylors and for Whitechapel. I think the problem was, this was misinterpreted by Whitechapel at the time as a permanent decline in bell founding.

Bell ringers

There are something like 40,000 bell ringers, but most of them are elderly. There's this feeling that because you have all these elderly bell ringers and not large numbers of young ringers, that bell ringing will decline. As bell ringing declines, then it follows that the bell foundry industry will also decline because there will be fewer projects. But actually what's happened is a lot of these older ringers have said, "Well, while I'm alive, I want to get the bells restored". So, by about 2014 the work was actually picking up quite considerably. What Taylor's did was to adopt very aggressive marketing, very competitive prices, free quotations, and as soon as they heard a whisper that a job might be going, they were writing to say, "We'd like to quote for it".

So what happened, was they simply, as the market was taking off again, creamed off the big jobs and Whitechapel went into quite a sharp decline. Its marketing strategy didn't change, and it simply lost the ability to sell its own product. It was a very good product, and I know the Taylor fanatics would argue against my comments, but what Whitechapel was producing, was better than in many ways than that of Loughborough.

The bells look better, nicer castings, more solid castings, the inscriptions are much nicer, and they're very nice bells, producing very fine rings of bells in the last years. But despite this, Whitechapel lost the ability to sell its product and went into decline, and of course, eventually, it closed. That was that as they say. It still exists on paper because the Hughes family kept the Whitechapel Bell Foundry company. It will take in enquiries, and it passes onto bell hanging companies or the Westley Group to quote for new bells.

Taylors still has plenty of work. They're very, very busy. In fact, they've taken on extra staff. They do well because they believe in themselves, and this is evident in their marketing and excellent website.

[Whitechapel Bell Foundry employed] around 25, but of course, in the last few months it started shedding people until we had really only a skeleton staff. The last few weeks we must have been down to about ten.

Local changes

In my time in Whitechapel from 1976 onward, of course, the area has improved enormously. When I first went there, there was lots of down and outs. There were people obviously living in extreme poverty, and I know that there still are, it's just it's not as visible anymore. But, there were people that lived at Booth House and other Salvation Army houses that had nothing, and these were the hardened meths drinkers.

I remember once somebody said to me, "You'll notice that the Irish and the Scots are really – they're the hardened down and outs. With the English, you get a better class of down and out." I said, "I don't really think it works like that," [laughs] but it was quite an interesting comment somebody made to me back in the 1970s when there was no such thing as being politically incorrect. But these people had nothing, and they used to beg, and with that that they gained sometimes, they would buy themselves a meal or their next bottle of cheap wine or whatever.

Of course the whole area was run down. There were lots of decayed buildings, and there was very little for many people. But of course, what we did have was the Jewish community, we had Bloom's, and we had all these Jewish shops which gradually disappeared, dwindled over the years. We had a synagogue, which I think still exists, it’s almost next door to the mosque. Of course, the jewish community virtually all moved out, they seem to have all disappeared into the suburbs.

It's history repeating itself because this is an area which used to be noted for immigrants moving in, settling, making some money, and then moving out. We've had the Huguenots, we've had the Jews, and I think we've had some Eastern Europeans, and I think a lot of people have established themselves. It's almost like a centre for people to meet, form their own communities, get themselves up and running, form their own businesses, then off they go. That's all history repeating itself. I dare say in thirty years or so, most of the Muslims living here will move out to the suburbs, and we'll have another group moving into the area instead. That's just the way it is.

Certainly, the period that I was at the foundry, the area improved quite considerably. The bomb sites, even in the 1970s, had been built on since. The only thing that actually made life difficult in the foundry was that it – when you turn off the Whitechapel Road, you go in towards Fieldgate Street on Plumbers Row. It used to be just a clear road, and then they put this large triangle in with a garden and shrubs, and it made it very difficult for lorries doing deliveries because they had to go around it and then reverse into the foundry. The same problem exists at Tesco which is on the opposite side of the road. That's something the Council did that didn't help the foundry one little bit, it was really quite awkward.

Of course, over the years, more and more cars – although there were car parking restrictions, people used to park their cars outside the main foundry gate, even though it said "No Parking". So a lorry would come along to deliver some bells or collect something, and you had to wait till you found the person who owned the car and remove it. So from that point of view, it became more inconvenient. I suppose you could say although the building did its job, it did it with some difficulty.

Working in the building

Well, it was always a question of making do. Back in the 19th century, it was mainly a foundry, it didn't do much else. It was Thomas Mears who had the frame building or the erecting shop built in about 1810 or perhaps 1820. Because, prior to that, what the Foundry tended to do was just make bells and sell them to bell hangers. It did make some of the fittings, but eventually, it started to produce a complete product. It built its own frames, it provided all the fittings. Of course, by the 20th century, it was becoming quite a struggle. They made quite some large bells, not just Big Ben, the big bell of Montreal, and the Great Peter of York has obviously been recast.

It had a large pit where they used to cast bells, but in those days, all they did was make the bell moulds underground in a pit, bury them in the ground, cast the bells, dig the bells out, and take them out into the works. A crude tuning machine enabled the strike note to be tuned. Along came the 20th century, harmonic tuning and the introduction of modern fittings, so we couldn't just make the bell, we had to tune the bell as well, so a new tuning machine was required

There was always a lack of height. It wasn't so much a lack of lifting equipment, it was a lack of height. The moulding shop really was quite awkward, and as soon as you started making bells much over one and a half tonnes, you had to start using the pit. You had to put them down in the pit to cast them, and if you made anything much over two tonnes, the best thing to do was to build the core in the pit and to lower the cope down because it gave you a little bit more headroom.

There was a very dingy shop where they used to build the frames. Of course, that was rebuilt in 1980. It had more height, it had two decent cranes, and had good lighting and better heating as well. The heating was something that improved gradually over the years, and actually, in the last few years, it was quite a comfortable place to work. The roof leaked, but not badly, it was something that we sort of kept on top of.

The building did need work done to it, there's no doubt about it, but it was quite habitable. There was plenty of light, we had decent heating, so you didn't tend to boil too much in the summer, and you didn't tend to suffer too much in the winter, so it wasn't an unpleasant environment to work in. The other thing that improved was the dust extraction. They installed a series of extractors in the late 1970s, and that immediately made the environment very much better.

If you went up to the carpenters’ shop, there's a whole range of memorial boards. I don't know if you've ever been there, but you'll find photographs of them on the web, A whole series of boards from about the 1880s or 1890s, up to perhaps the late 1990s – members of staff who have worked at the foundry.

Some of them had retired, some of them had died, some of them had died in harness. Lots of these people died at a fairly young age, in their 40s, 50s, 60s. There were a few exceptions, but not many.

The thing that we became aware of, as we were going through our careers, was that we were living longer, we were fitter, we ate a better diet. Formerly, most of these people lived in poverty, in social housing, in dank tenement buildings. We were starting to live more comfortably, moving out to the suburbs, buying our own homes, centrally heated, eating a good diet, plenty of exercise, so we were living longer. And that's something that we've thought of, became aware of, subconsciously at the start, but then we actively spoke about it, certainly in the last few years, and it must've applied to other factories as well.

I remember people who used to work in heavy industry, and often if they did make it to retirement, they don't even last a year or two, because they didn't have any money apart from their old age pension. They'd sit in front of the TV all day, and within a year or two, they're dead. But we were much more active, not just bell ringing, but all sorts of other things. And we lived better lives, in a better environment, and the foundry itself became a much better environment to work in. As a result of that, we haven't suffered nearly as badly.

The end of the foundry and the future of the site

[Alan Hughes] might possibly have found a buyer. When the foundry was a going concern, I expect he could've found somebody to buy it. My guess is, what would've happened, is that he would've sold the business, not the building. Because what they could've done, is to sell it to a new group of directors to run the business, but the Hughes family would have retained ownership of the building and charged rent. Being so near to the city, they would've made quite a decent living out of that. So that's one way out of it.

I think their problem was they had this very strong, almost obsessive belief in it being a family business, and despite the fact that it changed families so many times – we had single generations as well as families, we had the Mears family, and the Bartlett family, but lots of people were a one generation owner. I don't think previously people had thought of it much as a family business, and William and Douglas never really thought of it as a family business. I think the last generation reached a state where they couldn't see beyond that, it was a family business or nothing.

I just don't think they could see beyond that to the bigger picture, that they were just part of this enormous, great history. They had two daughters that weren't interested in the business, and exactly the same thing happened with Paul Taylor, of the Taylors. He had two daughters that were not interested in the business, but he had a son who died of leukaemia when he was eight, and I think at that point he decided that was the end of it. But in fact, what did happen was there was a rescue package. When Paul Taylor retired, the company continued, albeit under a new name with some new directors. It could've happened at Whitechapel, it just didn't.

[Alan Hughes] ran out of steam and he wanted to retire, so I think that he couldn't see a way forward. It was a declining market as far as Whitechapel were concerned, and I think he was worn out. He'd slogged away at the foundry, working long long hours day after day, since he was about 18, 19 years old. I think he had done enough.

Well, of course at the moment we have Raycliff, that owns the building and is seeking a change of use, turning it into a boutique hotel and themed cafe and a small foundry. What I'm hoping for is something on a larger scale. I mean at this point, what I do need to say is that there is this campaign to save the bell foundry building for continued use as a foundry.

The bell foundry is gone and most of the equipment has gone. It's been sold to other companies, factories. The Westley group have the moulding equipment but don't use it. They use modern moulding techniques, they use bonded sands and patterns to make the bells. None of the old equipment is now being used, it's just sitting out in Westleys yard, slowly deteriorating. We would use modern moulding techniques and source modern equipment, so we do not require the redundant Whitechapel moulding equipment.

What I'm hoping for is that we can reopen it as a bell and art foundry. "Save the bell foundry" is just that: save the building for continued use as a bell and art foundry. We want to make it into a more diverse foundry. Art foundry work is very lucrative. The Westley Group do art castings and there's an awful lot of art commissions, some of them small scale, some of that repetitive work. We already have several potential orders, some on a large scale.

I can see a success for the building as an art foundry that will also make small and medium sized bells. What I was thinking of was to make small-scale Liberty Bells, Big Bens and other famous bells to sell. And another thing we were planning to do was to digitally record famous bells. It's quite interesting that Raycliff have taken up on this because they've told me that's one other thing they would like to do, to digitally record bells. They too think that's a good idea.

[In the alternative proposal] we are proposing to use most of that front building as an art foundry. We would have a museum but it would mean a much smaller scale than that proposed by Raycliff. It's going to be mostly foundry work. One of the proposals made to Raycliff, which they've rejected thus far is that we have the front of the building for the foundry work and they demolish the 1981 building and build their boutique hotel.

I thought that was a reasonable compromise, but clearly, they don't. That would work because they don't have to try and come up with some solution for the old building, which is listed anyway, they can just get on and build their Boutique Hotel.

But there is work to be done. There's damp proofing to do, the roof needs heavy repair if not replacement. There is a lot of work to do, but what would be quite practical is to sort out the roof first and the damp proofing and then once the building is all up and running to carry on with restoration work thereafter.

The plan is apprenticeships, because there are not many opportunities for people to learn the art of moulding and casting, but a superb opportunity presents itself with a revitalised Whitechapel foundry.

Upstairs where the shops were for assembling hand bells and the carpenter’s shop, the plan was to let those out for artists. ... I think that the way that the foundry can continue into the future and also be profitable is going to be art casting as well as bells. Bellfounding will continue as an important feature of the revitalised foundry but we will diversify. We've got Taylors at Loughborough making bells and the Westley Group at Newcastle-Under-Lyme are now casting bells, and I think now that we cannot be especially profitable by just manufacturing bells, but combined with an art foundry, there is no reason why it can't be very successful.

Nigel Taylor was interviewed on 25 April 2019 by Shahed Saleem, and contributed this edited transcript.

Alan Hughes talks about the history of the Bell Foundry since it has been in his family's hands

Contributed by Survey of London on May 14, 2019

Previously, [before my great grandfather] the company had been owned by the Mears family for four generations. That's very roughly 100 years. The last Mears hit hard financial times, and took into partnership a man called Stainbank, who was from Lincolnshire, he was a timber merchant, but above all he had money. The Mears and Stainbank were only together for 10 years, 11 years, something like that. When Mears died, Stainbank, who was clearly younger, inherited the business. Stainbank, when he died, left the business in his will to his nephew, a chap called Lawson, who was a retired Indian bank manager. That was 1884.

Lawson, being a bank manager, knew nothing else about anything except banking, inherited this business, didn't understand what the heck was going on but realised that it was a business and it was running. His inheritance pretty much coincided with the arrival of my great grandfather, who at the time was a very keen bell-ringer, but importantly worked for a company, I believe, in Vauxhall, a foundry I think it was in Vauxhall. The nub of it is this: he used to visit here on a regular basis selling this company metal. He came in and found this chap Lawson sitting at his desk. They obviously fell into conversation, and at the end of the conversation, Lawson offered great grandfather the position of general manager.

My great grandfather came here as general manager. He was only 22 years old. He ran the company for Lawson. When Lawson died in 1904, great grandfather wrote to Lawson's widow, and I don't have a copy of the letter. It was a letter, apparently, in which he explained why he felt he was entitled to have first refusal to the purchase of the business, having run it for Lawson for 20 years. He made an offer, and I don't even know what the offer was. But it only took her three days to say, "Yes, fine," because she didn't want it. That gave great grandfather ownership of the business, but not the property.

Because when George Mears had taken Stainbank into partnership, the ownership of the buildings and the land remained with the Mears family, who through marriage became the Venables family. In 1960 agents acting for the Venables family said, "Look, we don't want this property anymore. We want to sell it. You inhabit it, therefore we're giving you first refusal." They asked in 1960, it's laughable today, but they asked for £20,000. Which was hard, so we took out a 10 year mortgage in 1960 on the buildings and the land. That meant that in 1970, 10 years later, the ownership of the buildings and the land passed to us as well as the business.

[For the 100 years previous to that] We’d been renting it, paying rent. Exactly, paying rent. The interesting thing too is going back into the sales day books. The Mears family themselves owned different parts of the business. One of the Mearses who was never taken into partnership was a John Mears. He seems to have been the black sheep of the family, but I don't know why. John Mears owned the very far rear of the property, and every month, John Mears was paid rent for that by the partners. We also do have the contract of partnership agreement between Charles and George Mears which is a very lengthy document. When you read between the lines, they really did not trust each other.

They may not even have liked each other but even if they did, they clearly didn't trust each other. That was the Mears family, but because it went very rapidly, Mears, Stainbank, Lawson, Hughes, we have no connection to the Mears family at all. We know nothing about the Mears family, and really the only thing that we have inherited are the sales day books. As a family we have no knowledge of them. We know they came from Canterbury. We know that the first William Mears became either bankrupt, or near bankrupt in his early years. We know that the prosperity of the company grew very rapidly and seems to have peaked some time around 1830, 1840, when Thomas Mears was clearly a very wealthy gentleman.

He was in the list of the first commissioners of income tax in this area when commissioners of income tax started in about 1820 I think. If you go into Highgate Cemetery, go in through the main entrance, the first thing you'll see is this enormous thing, which is the tomb of the Mears family. To have had that position and that size of tomb, you must have had money. The whole history of the Mears family is set out on this tomb in Highgate Cemetery. On a number of occasions I think Charles Mears and also George Mears, possibly Thomas Mears, were in turn masters of the family's company. Clearly, they were people of substance and people of some wealth.

I don't know whether they lived here in the bell-foundry house. I suspect that they did initially, but as they became wealthy, this wasn't a cool place to live, was it? If you look at the property map of this area, this wasn't, and so towards the end of their tenure, they had a foreman whose name was Warskitt. I think it was Warskitt, and I think Warskitt lived here. The Mearses lived in a more fashionable area, but again, I don't know where they lived. Stainbank, I think, lived in Camberwell. Where the Mearses lived, I don't know.

[My great grandfather] came here in 1884, same time as Lawson's manager. He was Lawson's manager from 1884 to 1904…We have been very careful to brush out some of the history there because in fact Albert Hughes [my grandfather] was the oldest of three brothers, Leonard and Robert. They both disgraced themselves. First of all, Leonard in about 1919, when he tried to sell the business behind my grandfather's back to George Co. and 600 Group. When my grandfather protested that he would have nothing of it, then Leonard Hughes said, "Well, in that case, I'm leaving because this company has no future."

He quit. So he has been airbrushed out. Then the other one was Robert Hughes, who was the bookkeeper. He kept the books, did everything to do with the money. For some reason, there was an audit undertaken here round about 1929. The accountants found that Robert Hughes had been augmenting his salary on a regular basis by fiddling the books. He was dismissed and disgraced which left only my grandfather. Those pieces of information have been airbrushed out of the official story.

[Albert Hughes my grandfather] was the oldest. He was the senior partner. As far as I know, he was the only one of the three who was actually a bell- ringer. He was, like his father, a very, very keen bell-ringer. Very good bell-ringer.

Douglas [my uncle] was about six or seven years younger than my father [William Hughes] when he came into the business. My grandfather was convinced that, just as my great grandfather was pretty much convinced that, the company wouldn't survive. .. When my father William, and my uncle Douglas left school, he ensured that they had good employment away from this company.

My father started work at the head office of the Thornycroft Company in Smith Square. They made trucks, diesel engines, that kind of stuff. Douglas started work with an insurance broker, Price Forbes as they were then, but the name has changed since they've been amalgamated with other firms of insurance brokers. He was convinced that when his time came the company would close, but my father decided that he would join his father. Which he did in 1945, and of course we're talking war years when we weren't making bells, we were making aluminium castings for the Admiralty. Then after the war, of course, the demand for the bells hugely increased because, of course, war damage and bombing.

We had this huge amount of work to do immediately after the Second World War but with fewer people to do it because they had gone to war and not come back. I don't know the whole story but my uncle was either persuaded to join with his brother or he decided to join with his brother. I don't know which but they both came into the company.

Again, because we were so short of skilled trades, both of them worked in the foundry extensively and also went out doing bell hanging work extensively because it was an all hands to the pump situation. Life was difficult. We had war damage, obviously, and yet a full order book and yet very little cash, and materials were rationed, so you had an order to build something but you couldn't buy the materials to build it anyway.. These were very trying times and, of course, I joined them later on.

It was quite an exciting time because only from 1970 did we actually own the property… because it had been mortgaged from '60 to '70. We were paying rent on it prior to that. In a sense, it wasn't for us to throw fireplaces away because we didn’t own them anyway. Also, we had decided to do some rebuilding once we owned the property. This was a great time of clearance and let's clear the decks and start again.

The facade has had very little done with it over the years. If you look at photographs of the facade from the 1920s, there is the most enormous and ghastly enameled sign right way across the parapet that says 'Bell Foundry.' Even if you look at the brickwork today, you'll see that the brickwork across the parapet looks a lot newer. I suspect that the parapet was rebuilt. Not just because the bricks look newer, because also it's upright. The whole building leans but the parapet is upright which suggests to me that it was rebuilt. The rest of it has been patch repair.

Again, going back to the time when I joined the company, all of the timber work right the way across the whole of the front was grained in the same way as our front entrance was grained. Now, I personally hate graining. It's just a thing. I don't like it, I think it’s horrible. It pretends to be what it isn't. I would prefer if they just paint it. It took us something like two years to get permission from the local council to actually paint the house timberwork green as it now is. That was a real struggle but at least visually, there is now some separation between what was the bell foundry house with the green and the front entrance, the business, which is still grained.

It's got to be 25 to 30 years ago. Ever since then, any repainting, and it's due for another repaint, any repainting has had to be in the same shade of green because if you change the colour of the paint in a grade two style listed building, you'll have to get at least a planning consent just to change the colour of the paint.

My grandfather died in August 1964. Although I can remember him very clearly, it was as a schoolboy. I started work here in August 1966 [aged 18], so he was already dead but my grandmother still lived here…I started in what we call the loam shop making moulds and casting tower bells. That's where I started.

The Bell Foundry during and after World War II

I've never lived here… This was my grandparents' dining room…It also doubled up as a living room. There was a desk over there. My grandmother was a great writer of letters, so she would sit over there and write letters. .. Well, just behind the door and there was an armchair in that corner and there was an armchair in this corner. Then, there was a radio there.

The panelling was very badly cracked, I understand, by the time we came out of the Second World War. We ourselves here, our own carpenters did huge repairs to this panelling. It was done very carefully. What you can't see is where the splits run down the centre of the panels, they took the panelling out and screwed into the back a series of brass strips which stitched the crack. They stitched the cracks together and then they filled the gaps and they painted over them. But the brass plates just stopped the splits moving.

The repairs to the panelling was done around about 1950. It was to try to make the place half decent after the Germans … I think [the building] survived [WW2 bombing] for two reasons. The first was there were no direct high explosives but were loads of incendiaries. Most of the damage that was done in the East End of London was incendiaries, it wasn't high explosives and it was that the East End burned rather than just being bombed.

Fire did as much damage as high explosives. The Germans were dropping incendiaries, loads of them. This place caught fire loads of times. But because my grandparents and my parents lived here and my father had a reserved occupation. Douglas went to war, had a great war actually because nobody shot at him. But my father was here on reserved occupation, so they would be up all night putting fires out.

There's nothing wrong with a fire provided you put it out quickly. It's if you don't put it out, it becomes a problem. [laughs].. They had buckets of sand and buckets of water and fire extinguisher and all that to the ready. As soon as something caught fire, they'll be running around on the roof putting fires out.

That's why it survived. The following morning they would have to patch the roof again or there'd be glass broken in windows, all that kind of stuff. Providing there was electricity, and there wasn't always, providing there was electricity, you could run the machines and we could continue making aluminium castings. Some days, of course, there was no electricity. Other days, there was no water. Other days, there was no gas. You took each day as it came because that's what happens in war.

The houseman and his work

This was the dining room. Their bedroom, my grandparents' bedroom was the room up here directly above… The room at the back which is now an office was the kitchen… The room above, the next room on the first floor there was the living room.

But the living room was pretty much set out most of the time with musical handbills because my grandmother was a solo hand bell ringer. She used to rehearse, she used to practice in there. She had this large table with all these bells laid out. She didn't have to put them away. She could go in there and just ring bells. That was only cleared away when she got older and she gave up hand bell ringing. Then my grandfather decided he liked to have a television, so the television was up there but the radio was still down here.

Then, the top floor, I never got to visit the top floor until, gosh, 30 years ago because my grandparents and then my grandmother always had a houseman. Somebody who would clean the place, light the fires, clear the ashes but also make teas and coffees for the office.

My early memories here from the '50s and early '60s was all of the offices had coal fires. This was the coal cellar underneath. There was a wooden trapdoor just outside the pavement which has now been covered in concrete but the concrete marks where it was. The coal used to be delivered loose seven times at a time, then large lumps were broken up.

It's almost a full time job if you've got fires in all the offices and the house in the winter just going around, lighting the fires, clearing the ash, leading the grate, breaking up coal. That's quite a job. But he [the houseman] would go out and do all the shopping, he'd keep the place clean. He actually had [two of the rooms on] the top floor. So it's only when my grandmother died in 1972, I think, John Hill continued to live here for another couple of years until he died, and then and only then did I actually get to visit the top floor of the house. Because it was his apartment, I never went there.

2 Fieldgate Street

What is now our shop is actually the downstairs room of No. 2 Fieldgate Street. That was his [a jeweller’s] shop. Sclaire, was his name, Sclaire's shop. He lived in the house above so we had no access to that. Yes, it's here. Sclaire died and one of his relatives, oh crummy, was it a nephew or something, tried to claim that he had the right to live there because he had always lived there, but he hadn't.

A long protracted legal battle then ensued in which we had to find all manner of people who lived here who would swear in a court of law that this guy didn't live there, they'd never seen him before in their lives, and the court found in our favour. That meant that we had the use of those buildings. But we did not have the use of that room or that room, because that was part of the territory that Sclaire occupied.

Sclaire was paying rent to the Venables family, just as we were, and then of course, but Sclaire was evicted before we bought the building, so Sclaire never had to pay rent to us, because by the time we'd purchased it in 1960, Sclaire had gone.

We turned the first floor room .. into a workshop and subsequently it became a drawing office which it still is, and the top rooms were just used as storage, which they still are. It's just a dump. It's a disgrace, really. It's just a dump.

No. 2 Fieldgate Street, we are told, is older than this building. So No. 2 Fieldgate Street was there anyway and then this was built up to it. The GLC dated No. 2 … on the basis of the glass being flush with the front of the building and apparently that puts it prior to 1690 or something.

I don't know and, to be honest, I don't care. [laughs] The other thing I'm told is unusual but not unique is you look at that door, and you think, yes, well, it's got stone facings. Well, they're not. They're timber to look like stone. Again, the GLC said this is an indication of relative poverty. It was the thing to have stone round the door, but if you couldn't afford it you dummied it up in timber and painted it the colour of stone.

How the houses have been used

This is No. 2 Fieldgate Street. But that door is now simply a fire escape. We don't use it for any other purpose. [The drawing office is on the] First floor, and those two windows is just a store. It's just a dump where we store stuff. Actually that room is a bathroom, and is currently used from time to time by our daughters who are living in those two rooms [that used to be the houseman's flat]

[The first floor is what] we call .. the library, which is pretentious. It's just where we keep our old books. This room, has, our elder daughter is an accompanist, that's how she earns her living, and we got a grand piano in there so that's her practice room. Also, if she's having to rehearse, quartets, quintets, whatever, they can come here because they don't disturb anybody.

Here, here is where the piano sits.. The rest of the room is largely unaltered. But we do about eight to ten times a year we have evening receptions here. It's usually for city livery companies or ward clubs, city organisations, who wish to bring a group to view the foundry, but also they then stay on and we serve drinks and finger food and stuff. That is served up here. All three rooms have interconnecting doors as your drawing correctly shows and so we lay food out in here. This room now, we call the red room because we've painted it red, it's the coldest room in the house. It's right on that east corner. It's bloody cold, we thought we'd paint it red then.

I think when he [my great grandfather] was the manager he didn't live here. I think he lived in Leytonstone somewhere, but when he gained ownership of the building he moved in.

Yes, I'm not sure which, either that, or that, was his [my father’s] bedroom. There were two brothers and a daughter. Yes, that's right and my uncle had one room and my father had the other and at the back, where are we, we are behind that room, there was an extension put in around about 1825. That was a bedroom. It's now a kitchen, but that was my aunt's bedroom. I remember it as a bedroom. Brass bed and all that stuff. It had a certain smell to it.

Hughes family history

My father married before my uncle. He met my mother in fact when he was working at Thornycrofts, and they bought a flat in Lewisham. During the war, they got married before the war, because transport was so erratic, he was finding increasingly he was having to walk from Lewisham to Whitechapel and back again at the end of the day. There were no buses, trains out. There's a war, for heaven's sake.

My grandparents were finding it increasingly difficult to stay awake 24 hours seven days a week, so they quit the flat in Lewisham and moved here. There were the four of them in the house. Towards the end of the war, the war would seem faded away. It didn't suddenly stop because gradually we were winning this war, we, collectively, were winning the war and so air raids became less and less and less frequent as the Germans were gradually pushed back home as it were.

Before the war ended, I think it was six months or something before the end of the war, my parents bought a house in West Wickham in a very poor-- It was a new house, it was only two years old but it had been occupied by the Home Guard or something and there were tank traps in the garden, it was a right mess. They bought it for very little. My mother thought my father was absolutely mad to do it, but in retrospect it was probably one of the wisest things he's ever done.

They actually set up house there just before the end of the war. They lived there right the way through. My mother in her '90s then asked to be moved into sheltered accommodation, because she couldn't maintain the house. So for the last three or four years she lived in the house. That's where they lived and that's, obviously, where I was brought up. That was my home.

My uncle Douglas, he married. I don't know how he met his wife, I've always assumed he met her at Price Forbes but I don't know. They married, it was either during the war or towards the end of the war. They initially bought a house in Hayes so they weren't that far from my father and mother. That's Hayes Kent not Hayes Middlesex, and then from there, they moved to Merston. Then from Merston they moved to Chalden and then they stayed there until my aunt died, which would have been 20, 25 years ago, then my uncle sold the Chalden house and moved into sheltered accommodation .. and then he died. That's the history.

Works to the front wall in the 1970s

In the 1970s the GLC were monitoring this building because the front facade was…, slipping gently into the road. We think the problem started with the building of the underground railway because the District Hammersmith and City Line goes straight down the middle of Whitechapel Road. They didn't tunnel it. They dug a huge trench and put a bridge over the top because it's only just below the surface. We think that the holding back of the earth wasn't done with sufficient rigour, and therefore the lands started to slip into the trench slightly before the bridge was built.

It's only the front rooms that are shifting. You can see this room is going. This corner, that corner is about nine inches out of plumb which is a lot for just a two-storey building. The GLC put monitoring all over the place and they came along every six months or something with laser things. They were able to demonstrate that the building was moving at an accelerating rate. So we were faced with doing a number of things. Firstly, there was a great crack down this corner because the facade was tearing away from the end wall.

Stainless steel anchors were put through the thickness of the brickwork to just hold the crack, not to pull it back. You can't pull buildings back but you can stop them going further. That was done. Also they found that this building has no foundations. The bricks just sit on the earth.

They corbel out for about three quarters. That's all. Which was typical of the day. In the cellar here on the front wall, the foundation company came in and they hand dug in metre sections down till they got to the gravel which is underneath the clay. They then cut into the gravel by one metre and they cast a one-metre square concrete block starting one metre below the gravel coming right way up to the underside of the wall. When the concrete had cured they then rammed a non-contracting grout in the gap. When that had cured they'd go and do another bit so they stitched their way round. The whole of the front is now supported on this enormous concrete block thing which goes down into the gravel bed.

Also, I'm told, I haven't looked for the evidence, they put in chains running through the depth of the floor to tie into this back wall so that these walls are also constrained. There are resin anchors into the brickwork in the front and it's either chains or tie bars that go back through the depth of the floor and cut into that part of the building which isn't moving.

We had to have an architect and an engineer come in and do it. We had a grant from the GLC towards the cost of doing it… I didn't handle the grant details. My uncle did that. No, he didn't. The architect did it. A guy called James Strike who is now retired I think… He’s still around. I haven't spoken to him for years but the reason I know he's still alive is within the last 18 months someone who came here said that he knew James Strike and James sent his best wishes or something to that effect. That was him. He retired as an architect and I think he found being an architect hard work and he went into teaching architecture at a university or college somewhere but I don't know where.

Derek Kendall photographs the building

The last interest that we had was from English Heritage who sent a photographer here [in 2010] to photograph the interiors.

We're in some English Heritage hidden London interiors book. It's funny because he came here by permission and by appointment and he was going to take these pictures for this book and we said that's fine. He said, "I'll only be here for half a day," and we said, "Fine," and at lunchtime, he said, "Can I stay here the rest of the day?" We said, "Yes, it's okay. " At the end of the day he said, "Can I come back tomorrow?" He spent three days.

The thing that fascinated him, strangely, most about this building was the staircase. He got really really excited about that staircase and it's just a staircase but he said the thing about it is that, obviously, it's 1738, but he said it is unaltered. He couldn't bring to mind another London property where he had seen a staircase unaltered since it was constructed. Dan Cruickshank, he did some filming here. It was a program he was doing something to do with London sewers. It was quite unsavoury but he got excited about the door furniture on the front door here because although we've added to it we haven't taken anything away.

The original door furniture is still attached and he got quite excited about that. The Queen, when she came here was saying what wonderful buildings these were. I said poverty is a great way of preserving the past. .. If you can't afford anything you don't do anything which means you hang on to what you got…

The workshops

The land that we had at the back, the bit in fact that has been rebuilt, was made up of two parts. Part was a huge wooden shed which was a workshop and it was the wooden shed that we were wanting to remove and replace. Also a yard. Now the wooden shed projected into next door's property, but we owned it. But it was a nuisance to them because it was like a peninsula of land sticking into their land. At the same time between that shed and Plumbers Row there was an open yard. The open yard belonged to them. So they had this little isolated plot of land that we were occupying that they owned.

We owned land effectively in their property. So prior to the rebuilding work we had an exchange of property and it was done on a square foot for square foot basis. I don't think either of us actually gained square footage. But we took ownership of the yard and we gave them the bit that stuck into their property. That gives us the footprint we have today. Having exchanged those boundaries we then set about clearing the whole site and then constructing new workshops. They don't look new anymore but they were new 40 years ago… 1980, That is the construction of those workshops.

The foundry is incredibly quiet today because we have a policy with holidays that you use it or lose it. Our holiday period is in end of March. Purely coincidental this is just about half our staff are on holiday today, and I've already mentioned that.

Walking around the house

The mantle shelf is new. Because they didn't have mantle shelves. Mantle shelves came in Victorian times. The other thing, of course, from the 18th Century and that is that you didn't designate a room for use. You would move the furniture around according to how you were intending to use the room. But, again, the GLC seemed to think that this room was used for food because of the marble.

Yes, marble apparently was relatively expensive for people who were poor. You didn't go splashing out on marble but marble was used for setting out food because it would keep food cool all the time. They thought that in the original plan of things this room was probably used for serving food because of marble. I said, "But it's on the first floor. Why would you carry food up the stairs? That doesn't make sense." They said, "But they used to do that."

[The kitchen was] Downstairs right in the far corner [on the ground floor]. So everything had to be carried up the stairs. But I've nothing to support that opinion. It's just, and again, it was given verbally by a GLC architect.

It could even be that at ground floor level you've got smells, you've got noise from the street, you've got people banging on the windows. Maybe coming up to the first floor you've got a bit more privacy. Maybe it's just a nicer place to be.

This is where my grandmother had her hand bells. She had a table in the middle here and all the hand bells were laid out. So the room really wasn't used for any other purpose other than for her to practice hand bell ringing.

This is where Jennifer practices. .. That fireplace has always been exposed but it's not ancient. That has to be mid 19th Century because it's so over the top ornate.

It's almost Puginistic, isn't it? You can also see how with the building moving you've got that great split at the back of the hearth, because that's the bit that didn't move. This is sitting on this floor and it's coming away... We’re now going what 30 to 40 years since that was done. It doesn't look to me as if we're moving further. Of course, you can't put it back. You can feel the slope, can't you? This is the cold room.

That, again, was boarded up. We only took the boarding off there just over a year ago. Again, it had a gas fire and it was boarded. Having been encouraged by taking the boarding off in the library, my wife said, "I wonder what's behind here." We haven't lit this. I don't see why we couldn't. One of the mysteries is we had roof repairs done two or three years ago so there was scaffolding right up across the roof. I went in and inspected all of the chimneys and the intriguing thing is that every single fire has its own flue. The flues don't connect.

There's one more pot than I can find a fireplace for. Well, this apparently is something that people did because the number of fires is a bit like the number of cars. The number of fires you have is an indication of your wealth because coal's relatively expensive. The more fires you had the more wealth you had.

Walking around the property

If we go out to what we call the new back foundry-- we produced this drawing some years ago. This was done in house, but it’s a sort of cut away of what goes on inside… This is 34 Whitechapel Road.

These here really give you some idea of the history. ….. This room here was where we stored metal. And it was called Kimber's room. This was the bit that we owned. And I told you had projected into the next-door property.

That extension was acquired- we don't have a date for it - but it was round about 1820, 1830. That's when the Mears family fortunes, as it were, peaked. But I don't have a date for that.

This is No. 2 Fieldgate Street where we used to keep the music ... all the hand bell stuff used to be kept in the red room. Then of course, we're supposed to provide disabled access. Well, how are you going to get people upstairs? So we thought we're going to have to bring it all down stairs. A wheelchair will come in here.

So we can get wheelchairs into this area…. We also, from time to time, have groups from local schools. So we can take a few school kids in here, which is why that thing moves so slowly because if you're presenting it to children, who are sort of six or eight or ten years old, it needs to move a bit more slowly for them.

The back wall

Okay, structurally this fascinates me because this is the back wall of No. 2 Fieldgate Street. No, it isn't. Precisely. There's nothing there. There’s absolutely nothing there. That is a beam. That is a timber beam. And the whole of the side of the house sits on that timber beam. And above is a nine-inch brick wall. So you've got a nine-inch brick wall sitting on a timber beam.

Yes, and what makes it even worse is where the staircase turns, you would hit your head. And it's been cut back. And it's only two inches deep.

The yard started here. And again, this wall is half-an-inch thick. That's all there is, just half an inch. This panel here.

Well, we think it's 1825 because there's a fireplace through what used to be the kitchen. And it says ‘TM [Thomas Mears] 1825’. Right, okay, so going back through the rear door into the yard area.

When you look at the structure, you're thinking, "Hang on a minute. This doesn't make sense." This wall ends here. It's just a stud wall because beyond that is just half-inch panelling. Same thing here, the wall just ends there. And then all of this is just timber.

We’re pretty sure this is 1825 because of the dating on the fireplace. But you can also see that when the extensions were built, they came out as far as they could. They came out as far as that window edge.

It's all a bit of a mess really.

Various building works

This looks new because that was rebuilt in the 1960s. It was virtually falling down. So that was completely rebuilt then. And that's when the old well was discovered because being a coaching inn, it had a well. And this is the well pipe that went down the well. So that told you the depth of the well. And we filled it in and put proper foundations under this wall because again, this was a wall with no foundations. It just sat on the earth.

This now has a proper foundations. And this also was rebuilt. And that also has proper foundations.

I can just remember when that was the stable, in there, because I can remember the mangers were in there. But that's now our metal house. But that used to be a stable because, presumably, the chap who lived here had a horse.

The yard, of course, also extended further this way. And we know that because these aren't outside windows…

This wall was built in about 1840, when we put in our first tuning machine. And you will see that-- this machine was put in 1920. But it's kind of similar to the previous machine. It relies upon the building to hold it up. So because this was the end of the yard, all they did was put one wall across, and you create a room.

Well, this was what we did [rebuilt the cellars] in 1980, having done the land swap. And the people next door were very reasonable because they could see that, for a time, we would need both parcels of land.

They very kindly waived rent. They just said, "Okay, how long is this reconstruction going to take?" We said, "Well, because we got to keep working. We got to phase the work, so we can keep working." We said, "It won't take more than two years." And they said, "Right. If you do it within two years, we will waive the rent on this yard. But if you start dragging it out, then, of course, that's a different story." But we didn't. We just wanted to get it done.

A rare example of manufacturing in London

And the sad thing is, of course, that people don't understand manufacturing. If you say to people, a milling machine, [they have] no clue what you're talking about.

I think the fascination for people who visit is that they are visiting a dirty workshop, where stuff is made because they've never seen it before. And they'll probably never see it again.

... And we then put that frieze on the bell. To us, that frieze has meaning. It won't have meaning to anybody else, but it does to us. It's a frieze that we used in the early 19th century on bells. And the point about these two bells is that they have been made to an old style profile, so that they match in with the old bells that are already in the tower. We can look at that. We just say, "Well, it's an old-style bell." If it's a modern bell, it will have a different frieze on it. And I'd say that's a modern profile.

It's an interesting frieze, that, because for several years I owned a narrow boat. If you look at the decoration on narrow boats, the style of which dates from late 18th, early 19th century, you'll find the same frieze as part of the decorative paintwork on narrow boats. So clearly, it was a fairly normal kind of early 19th century, late 18th century style of-- It's a series of curves. It's a very simple geometric shape.

Dealings with the local council

I think also that because this place suffered neither the extremes of war nor the extremes of wealth, an awful lot has remained unchanged. It's continued to this day with the grants that have been given by national and local government. In 2012 or before 2012, there was High Street 2012, when Tower Hamlets Borough and presumably others decided to spend money restoring and improving the appearance of the properties down this corridor. Well, the money started at Aldgate and came to the end of the block. And it started at the end of the block and continued east.

And we were excluded. Then a couple of years ago, they decided on another system of improving the buildings. It came up to the end of this block. And it started at the end of that block. So every time money is spent on this road, this block is specifically excluded. Every single time. We applied to English Heritage for some grant aid ten years ago for restoring our chimney because our chimney is unnecessary, and it was in dire need of attention. They said, "No. We can't help you because it would be unfair to your competitors." But they have just given our competitors £3 million.

I’m thinking, "Why is it fair to give them £3 million pounds, but it's not fair to give us anything because we have a competitor?"

It doesn't make sense. I think Tower Hamlets would like to see us go because they have now rearranged the roads at the side - and we notified them of this - in such a way that it is impossible to reverse a vehicle into our gateway without going the wrong way up a one-way street. So the only way you can load or unload is illegally. There was no consultation. They rearranged the road. And we said, "Hang on a minute. Do you realise what you've done?" And they said, "Crumbs. Sorry." So they changed it. Six months later, they changed it back. They did the job twice. On large stuff, even illegally, we can't get a large vehicle into our work. So on large projects, we have to go to the expense of double-handling. We have to load here in a small vehicle, then take it to another site for loading into a container for export. It's actually put up the cost of our export work.

We have twice had people come in from Tower Hamlets saying that we have been reported for using solvents. Now, we don't use any solvents at all in any of our processes. Yet we've had environmental health coming here saying we have been reported to them for doing this. Well, of course, we have been reported because how can we be reported for using something we don't use? They spent a whole day here sniffing around the premises just being a nuisance. I think in a perfect world, Tower Hamlets would like to see us go. It's because this is turning into a residential area. And of course this noise and smoke and dust and all the things that you get with industry-- There's a hotel just opened at the back. So I don't think we fit in to what Tower Hamlets want for this area.

We tried to get permission from Tower Hamlets-- There was a bell ringers' event in London. And there is a small mobile belfry. It fits on to the back of a trailer, and it's towed by a car. We tried to get permission from Tower Hamlets to park it on the pavement to the side, which is why they said, "No, you can't do that because it might damage the paving stones." We said, "But vehicles pull on to this routinely." "Oh no. You can't do that." Then we had some repairs done to the chimney. And we said we would like to have a scaffolding built. "No, you can't have scaffolding at the front of the building at all. We won't give you a license for it because you might damage the pavement." Then we said, "Can we have a cherry picker to inspect the chimneys?" "No. You can't have a cherry picker because the cherry picker might damage the pavement."

So whatever we want to do, Tower Hamlets say no. So I think they would like to see us go. From my point of view, I think one of my greatest incentives to running this business is to ensure that Tower Hamlets don't get what they want.

But in the end Tower Hamlets will win because they always do. But we had large trees growing outside, which were disturbing the pavement. We were worried about disturbing the wall. And for years, we wrote to Tower Hamlets and asked them to have the trees cut down. And they ignored it. Then the Queen visited. And the tree was taken down the week before the Queen came.

We've also had to register with Tower Hamlets a letter holding them responsible for not enforcing parking regulations on Fridays because of the mosque. Because they don't enforce parking, which means that cars - depending on upon what time of year it is - they'll park against our gates, so we can't open them, and on the pavement. Historically, we cast on Fridays, big casts, because then the moulds cool down over the weekend. But if we were to have a fire, you can't get a fire engine here because they allow vehicles to park. And if you phoned up parking control, they say, "Oh, yes, no we don't. When the mosque is operational on a Friday, we don't enforce parking regulations."

So we had to go through our insurers on this, and I said, "But we've written to Tower Hamlets. And they won't reply." They said, "No, but if you register the letter, they will have received it. And although they won't reply, you know they've had the letter." So we've had to do that simply to cover ourselves in the event of fire, and the fire engines can't get here, and parking control won't have the vehicles removed. So they're only little things. They're petty. I mean, they're very, very, very petty....

Whitechapel and its future