The Royal London Dental Hospital

Block occupied by the Royal London Dental Hospital. Site of the former Alexandra Wing, built in 1864–6 to designs by Charles Barry Jr.

The Alexandra Wing, 1864–6 (demolished)

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 8, 2016

Over time, the hospital was increasingly inundated with patients arriving from the local area and remoter parishes such as West Ham. Since the completion of the wing extensions of 1830–42, the volume of patients had more than doubled. By the 1860s, more than 30,000 people were treated as inpatients and outpatients each year. Overcrowding was not confined to the wards, as medical officers and nurses endured cramped conditions with little promise of rest. Due to prolonged shifts and a lack of dormitories, nurses were frequently seen to be ‘overcome with sleep’ and the matron insisted that her staff could not be increased without additional sleeping accommodation. By 1862 the situation had become untenable and a report on overcrowding pronounced ‘a very serious defect in the arrangements of the London Hospital’.1

The hospital turned to its surveyor, Charles Barry Jr, to prepare plans for an extension to the outpatients’ department. Acting as hospital surveyor from 1858, Barry approached his responsibilities in an efficient manner from offices in Sackville Street, proposing to attend committee meetings for an extra charge in addition to a nominal salary and commission rate. Barry designed a long single-storey building that would run parallel to the existing surgical and physicians’ outpatients’ departments housed in the west wing. Yet plans for this extension were stalled as the House Committee contemplated a solution for the longer term. The matter was delegated to a building committee, which promoted substantial alterations and argued that ‘the entire system is one of undue pressure, subversive of sanitary arrangements, inconvenient to the professional staff, (and) unfair towards the patients and the servants of the hospital’.2

The proposed solution was to build a three-storey wing with a basement and an attic, extending west parallel to Whitechapel Road. Barry’s plan promised room for about seventy beds, with separate wards allocated for children, obstetric cases, and Jewish patients. The hospital had received a series of requests for the reinstatement of separate Jewish wards since their closure, but was limited by the pressure on hospital spaces. The wing extension enabled the hospital to arrange Jewish patients in separate wards on one floor, near to a kosher kitchen.3 The new wing was divided roughly into two parts. A three- storey maisonette with bedrooms and servants’ quarters was carved from the west end of the wing for the house governor, a resident officer who managed the daily workings of the hospital and its expenditure. Each floor of the east side of the building comprised a central corridor flanked by wards or offices. The basement secured a new surgical outpatients’ department, with an extensive waiting hall to make the customary ‘lengthened detention’ less onerous, and a consulting room flanked by rooms for dressing injuries. An attic dormitory for night nurses addressed fears that a lack of supervision compromised their efficiency and ‘quality’. The intermediate floors were given over to wards, with the exception of a new committee room and secretary’s office positioned on the ground floor.4

The exterior of the west wing reflected its disjointed plan. On the north elevation facing Whitechapel Road, a projecting bay capped with a pediment marked the junction between the wards and the house governor’s residence. The west elevation had a raised entrance porch to the house governor’s maisonette, which overlooked a private walled garden at the south. A significant innovation in the new wing was the construction of a narrow tower to contain sanitary facilities, specifically a water tank at its peak and water closets below. At Barry’s insistence, the building was constructed with fireproof concrete floors and staircases. The House Committee initially hesitated over the additional expense, yet was persuaded by the surveyor’s warnings that the hospital could be criticized for failing to introduce fireproof floors, which also possessed soundproof and ‘verminproof’ qualities.5

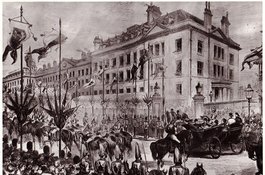

The new wing was constructed in 1864–6 by Hill & Keddell, contractors based in Whitechapel Road. It was financed partly by charitable donations, including substantial gifts from local businesses and the brewer Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, chairman of the House Committee. Many of the hospital’s staff and supporters were recognized in the naming of the wards: one was named ‘Buxton’, and ‘Davis’ commemorated the present and former vice-presidents. A ward was named ‘Blizard’ in memory of the hospital’s eminent surgeon. The foundation stone was laid in July 1864 in a ceremony that saw Whitechapel awash with crowds and decorated with bunting. The building was bestowed with the first name of the new bride of the Prince of Wales, an association intended to inspire ‘respectful admiration’.6 Its opening was not accompanied by such celebration; formal inauguration had to be abandoned due to another outbreak of cholera. In July 1866, patients were moved into the new wing to provide space for cholera patients.7

The completion of the Alexandra Wing allowed various improvements to be effected elsewhere in the hospital, as rooms were modified and reassigned. These alterations were also carried out by Hill & Keddell and continued until 1868. In the basement, an ophthalmic ward was set up and the medical outpatients’ department extended into rooms formerly occupied by its surgical counterpart. On the ground floor, the entrance vestibule was extended and a large receiving room added at its west. Bedrooms, sitting rooms and offices were provided to improve conditions for the medical officers and their pupils.8

Rowland Plumbe and Joseph George Oatley oversaw various alterations to the Alexandra Wing in the twentieth century, including the formation of a coroner’s court in the basement and a single-storey extension at the west. An endowment by James Hora, a vice-president of the hospital, led to the opening of the Marie Celeste maternity department in 1905. Due to persistent pressure on vacant space for hospital expansion, the house governor’s private garden was not destined to survive. By 1960 it had been converted into an ambulance station, with a covered parking bay and ramped entrance into the hospital. This in turn was short-lived, as the Alexandra Wing and the adjoining ambulance station were cleared for redevelopment in 1974.9

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/31, pp. 110, 200; RLHLH/A/5/32, p. 30; General State of the London Hospital (London: School Press Gower’s Walk, 1854), p. 8: Ward visitors and Mrs Nelson, matron, cited by Clark-Kennedy, London Pride, p. 110. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/31, p. 200; RLHLH/A/5/32, pp. 30, 257–8. ↩

-

Jewish Chronicle, 23 June 1905, pp. 14–15: RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/31, pp. 30, 110, 481. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/32, p. 30. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/32, pp. 30, 143–4. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/32, p. 104. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/33, p. 46–7; RLHLH/A/5/32, p. 78: Medical News, 9 July 1864, p. 61. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/A/5/33, pp. 128, 164, 197. ↩

-

London Daily News, 19 July 1905: Goad Maps. ↩

The Royal London Dental Hospital (formerly known as the Alexandra Wing), 1978–82

Contributed by Survey of London on April 29, 2019

The Royal London Dental Hospital stands at the west end of the former main hospital building, with a glass-fronted canopied entrance on the east side of Turner Street. This six-storey block of 1978–82 represents the first phase of the redevelopment scheme produced by Bennett & Son. Its large footprint occupies the site of the former Alexandra Wing, the Bearsted Lecture Theatre and the 1930s cardiology department. The block is clad with sand-coloured brickwork divided by vertical strips of stone cladding, which articulate its concrete frame. Screened from Whitechapel Road by a row of plane trees, the north elevation has narrow windows between angular brick projections. The west elevation has broad horizontal windows and louvres to ventilate plant rooms on the third floor.1

Plans for rebuilding the Alexandra Wing were approved in 1970, yet progress was marred by the listing of the original wing, initiated by the GLC in September 1973. The hospital proceeded with unauthorized demolition of the historic wing, but was instructed to halt work. A compromise permitted the hospital to proceed on the condition that it retained and refurbished the main hospital building. Demolition continued in October 1974, yet progress was suspended for financial reasons by the Department of Health. Building works were revived in 1978, with Higgs & Hill of Kingston engaged as the main building contractor. The wing was opened formally by Queen Elizabeth II in 1982.

The rebuilt Alexandra Wing secured a new operating department on the second floor, in addition to the theatres in the main hospital building. Each theatre was accompanied by rooms for anaesthetisation, scrubs, sterilization and waste disposal, conforming to modern requirements. The ground floor contained an accident and emergency department, which improved on the outdated facilities in the central block. A central disinfection and sterilization unit designed to serve the entire hospital was located in the basement, along with lecture theatres for medical students and trainee nurses. A radiodiagnostic and X-ray department was located on the first floor. The fourth and fifth floors contained laboratory spaces and libraries for medical research and education, while a sixth floor for private patients was not executed.2

A rooftop helipad constructed in 1989 provided the first base for the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS), also known as the London Air Ambulance, the first of its kind in the country. The first helicopter and its initial operating costs were funded by Lord Stevens of the Daily Express, with a remit limited to emergencies within the boundary of the M25 orbital motorway. The installation of the helipad precipitated a number of practical alterations to the Alexandra Wing, including an external lift with a 35-second descent to the ground-floor accident and emergency department. Other modifications responded to the increase in trauma patients at the hospital, including a new resuscitation room with radiographic equipment mounted on the ceiling. Soon afterwards, the ground-floor accident and emergency department of the Alexandra Wing was reconfigured and modernized to plans by Nightingale Associates. Patient cubicles were arranged around central staff bases to increase supervision and access to investigative equipment, translating to shorter patient visits. The reconfiguration provided an admission ward with twenty-eight beds, securing room for the overnight arrival of patients. By 1997, the department was responsible for treating around 80,000 patients every year.3

After the new Royal London Hospital opened in 2012, the Alexandra Wing was converted into a dental hospital and an institute of dentistry. This adaptation formed part of the second phase of the hospital redevelopment scheme developed by HOK International. The reopening of the building in 2014 secured an assortment of spaces for dental healthcare, research and teaching, designed in collaboration with clinicians and academics based at Barts Health NHS Trust and the School of Medicine and Dentistry at Queen Mary, University of London.4

-

RLHA, RLHLH/P/6/11/47; RLHTH/A/11/4: The Times, 25 March 1982. ↩

-

RLHA, RLHLH/P/2/6; RLHLH/S/2/36; RLHLH/X/83/27; RLHLH/X/5/6. ↩

-

‘Helicopter Emergency Medical Services – HEMS One’, Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Vol. 71 (1989), pp. 60-4: ‘The Royal London Hospital Helicopter Emergency Medical Service: First Phase 1990’, Ann. Roy. Coll. Surg. _74: pp. 130–45, 1992: ‘Ceiling mounted radiographic equipment for trauma management in the emergency room’, _British Journal of Surgery, 82(1995), pp. 71–3: https://richardearlam.com/trauma-helicopter: Hospital Development, March 1997, pp. 27–8: PA/89/00540; PA/89/00542: RLHA, RLHHE/S/1/7; RLHHE/S/2/1; RLHHE/S/3/1/1–2; RLHHE/S/3/2/10. ↩

-

Tower Hamlets Planning Applications, PA/04/00611; PA/10/00910; PA/11/00730; PA/11/03734; PA/11/02733; PA/10/00910/NC: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/items/smd/133611.html. ↩

'The London Hospital: Laying the Foundation Stone of a New Wing', The Essex Standard, 8 July 1864

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London on Aug. 17, 2016

Excerpt from The Essex Standard, 8 July 1864:

The London Hospital 'has found its increased accommodation more than outstripped by the rapid growth of population around it, particularly in the large parish of West Ham, in our own county, where year by year acres of marsh land bordering upon the Thames have been absorbed for railways, docks, ship yards, iron works, and factories of various kinds, each employing its hundreds of thousands of hands, and necessitating the provision literally of miles of new streets for the accommodation of this vast aggregation of artisans and of the trading classes following in their wake. Nor is the number of the population the only cause of the increase of applicants for admission: the manufacturing and commercial operations of the neighbourhood are constantly resulting in accidents to life and limb, and so strongly marked is this characteristic that the serious casualties treated within its walls outnumber those of the three other largest hospitals of the metropolis.'1

-

The Royal London Hospital Archives, RLHLH/A/5/32, p. 110. ↩

'Laying the Foundation Stone of the New Wing of the London Hospital', Medical News, 9 July 1864

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London on Aug. 17, 2016

Excerpt from Medical News, 9 July 1864:

The ceremony of laying the first stone of the new west wing of this Hospital was performed on Monday last by the Prince of Wales. Whitechapel wore a holiday appearance on the occasion, crowds of people welcomed their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess, and the thoroughfares were decked with bunting of all colours. Their Royal Highnesses were received at the principal entrance of the Hospital by His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge, the President, the Vice-Presidents, and the members of the Committee of the Hospital, who conducted them to the place where the stone was to be laid. When the Prince and Princess had reached the marquee under which the stone was suspended, and had taken their places facing it, His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge read an address detailing the operations of the charity, which, since its establishment, has aided 1,300,000 persons, and which is now greatly at a loss for additional room. His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales said that it gave him great pleasure, to join in such a work, and to assist his illustrious relative, who was ever foremost in works of charity, in commencing what, it was to be hoped, would be even a more successful career for that admirable Institution, the London Hospital.

When the succeeding applause had subsided, the Bishop of London offered up a prayer for the success of the work, and then a choir, formed of the gentlemen and boys of the Chapels Royal and of Westminster Abbey and St. Paul's, under the lead of Mr. Francis chanted a selection from the Prayer-book version of the 107th Psalm; after which the Prince, taking a silver trowel from Mr. C. Barry, the architect of the new wing, proceeded to lay the mortar. A bottle containing current coins of the realm, and a copy of the last annual report of the Hospital, was deposited in a cavity in the lower stone; and then the stone was lowered to its bed, the Prince giving it, after the architect had tried and found it true, three taps with a mallet made of a thorn tree as old as the Hospital, which grew upon the very spot where the stone now stands. Great delight was manifested by the spectators when the Princess, stepping forward, received the mallet and repeated the taps, giving at the same time one of those happy smiles which so well become her genial face — never, we are glad to say, looking better. The Old Hundredth Psalm was then sung in unison. The bishop gave the benediction, and then, conducted as before by the president and the committee, their Royal Highnesses re-entered the Hospital, and the Prince paid a visit to the principal wards.

The following are some particulars concerning the new building:

The proposed new west wing will be 140 feet long by sixty feet wide, and will contain in the basement story a large waiting hall for out-patients, Surgeons’ and Physicians’ rooms, laboratory, dispensing, and other offices. The ground and one and two pair floors will contain large wards for men, women, and children, together with separate wards for Jews, and suitable offices adjoining thereto. On each of the several floors will be the requisite rooms for nurses and other attendants. The dormitories will be fitted up exclusively for the sleeping apartments of the nurses and domestics connected with the institution, and it is expected that there will be accommodation for 200 additional patients, exclusive of the requisite offices for the attendants. The contract has been taken by Messrs. Hill and Keddell, contractors, of Whitechapel Road, for the sum of £23,000 under the superintendence of Charles Barry, Esq., the architect. At five minutes past two their Royal Highnesses, conducted by the Duke of Cambridge, entered a very large marquee, in which a dejeuner was laid for 1000 persons, and taking their places at the high table from which the others radiated — the Princess on the Duke’s right, the Prince on his left, and the Bishop of London next to the Princess — were welcomed by the company just as heartily as they had been greeted by the throngs of East End charity children, who, with their banners, were drawn up in the pretty gardens through which the Royal guests passed to reach the marquee. When justice had been done to the luncheon, the Duke of Cambridge, in a few words, proposed the toast of the Queen, which was duly honoured, and was followed by that of the Prince and Princess, given also by the Commander-in-Chief.

The Prince said: ‘After the kind and flattering manner in which my illustrious relative has proposed the health of the Princess and myself it would ill become me if I did not warmly return thanks for the honour you have done me. To encourage the great national institutions, in which myself and the Princess naturally take a deep interest, will ever give great pleasure to us. I have walked through the wards of the Hospital today, and I can bear testimony to the great general efficiency of the charity. I hope the new wing, which will be called after the Princess — the Alexandra wing (cheers) — will do much to relieve the necessities of the district. I wish that the wing may never be full. (Great cheering) I beg to propose to you “Prosperity to the London Hospital”.’

The toast having been drunk with enthusiasm, Mr. T. Fowell Buxton, chairman of the house committee, then announced the subscriptions towards the special object. Among the sums given these were some of the principal ones: J. Barclay, Esq., £1000 per annum for three years, £3000; Sir T. P. Buxton, Bart., £500; T. Fowell Buxton, Esq., chairman of the house committee, £3000; Charrington and Co., £500 per annum for two years, £1000; Octavius E. Coope, Esq., £500 per annum for two years, £1000; John Davis, Esq., V.P., £315; East and West India Dock Company, £500; Hoare and Co., £300; John Hodgson, Esq., £500; Ind, Coope, and Co., £500; Hon. Rustomjee Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, per R. W. Crawford Esq., M.P., steward, £2000; Andrew Johnston, Esq., £100 per annum for three years, £300; Mann, Crossman, and Paulin, £600 ; Lady Morrison, Three per Cent. Consols, £1000; Henry W. Peek, Esq., £315; Truman, Hanbury, Buxton, and Co., £1000. The total amounted to the enormous sum of £30,621.

The present Hospital professes to afford accommodation for 320 patients only, but from the numerous accidents and the number of severe cases occurring amongst the dense population in the neighbourhood, that number has often been exceeded. The Jews' ward, with the separate kitchen attached is a special feature of interest in the charity.1

-

Medical News, 9 July 1864, p. 61 (online: http://www.archive.org/strea m/medicaltimesand16unkngoog/medicaltimesand16unkngoog_djvu.txt) ↩

The Alexandra Wing of the London Hospital, as depicted in The Illustrated London News on 11 March 1876

Contributed by Historic England

Postcard showing the London Hospital

Contributed by Amy Spencer, Survey of London

The west elevation of the Royal London Dental Hospital from Mount Terrace in 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

The Alexandra Wing of the London Hospital (its west end) in the early 1970s (photograph by Dan Cruickshank)

Contributed by Dan Cruickshank

The Alexandra Wing of the London Hospital in the early 1970s (photograph by Dan Cruickshank)

Contributed by Dan Cruickshank