Liptrap gas-making plant

Contributed by mary2 on Oct. 8, 2020

Liptrap may have had a small coal-gas making plant - or seem to have enquired about one to Boulton & Watt in 1811 (note in Boulton & Watt archive, Glasgow).

Whitechapel Distillery

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 3, 2018

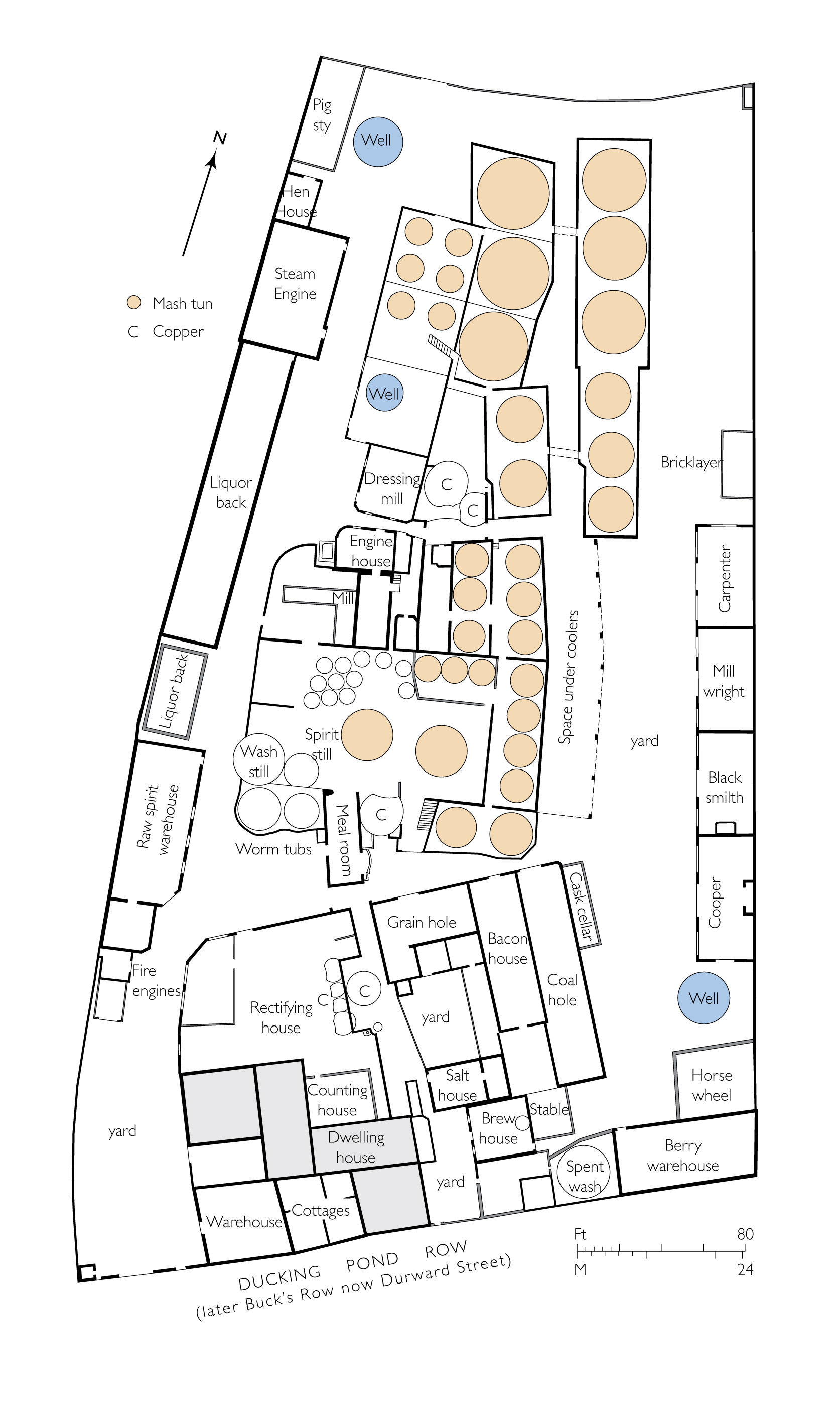

What is now part of the Whitechapel Sports Centre site and land to its east and north housed a major distillery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Samuel Davey Liptrap (1742/3–1789) was a starch maker who diversified to become a malt distiller, from 1767 holding premises at 25 Whitechapel Road and a much larger site on the north side of Ducking Pond Row, seven acres of heretofore open ground. Water supply was critical. Wells could be dug here where the canalised watercourse known as the Black Ditch ran and there was a windmill for pumping; the drying-up of the Ducking Pond at the east end of what is now Durward Street may have been a consequence. Liptrap was Master of the Distillers’ Company in 1788. Upon his death a year later he was succeeded by his Whitechapel-born eldest son, John Liptrap (1766–1826), who rapidly distinguished himself not merely as a distiller, but also as a magistrate, philanthropist and a Sheriff of London in 1795, by when he was running the distillery in partnership with his brother Samuel Davey Liptrap junior (1773–1836). John Liptrap’s most egregious claim to fame came in 1796 when he chased Prince George from his Whitechapel house on finding him in bed with his wife.

The distillery grew and prospered, producing around 7,000 gallons a day of malt liquor, or what were called ‘low wines and spirits’. John Liptrap became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1802. A year later his brother was under investigation for having allegedly siphoned off large quantities of fermented wort to evade tax. There were bankruptcy proceedings in 1804, and in 1811 a wider partnership was dissolved. John Liptrap crossed swords with Joseph Merceron, Bethnal Green’s potentate, in 1812 and was forced out of Whitechapel bankrupt.1

Whitechapel Distillery in 1817 (redrawn for the Survey of London by Helen Jones, from London Metropolitan Archives, SC/PM/ST/01/002)

The distillery had become a vast undertaking, London’s third largest producer of alcoholic spirits in 1820. A new artesian well to a depth of 106ft had been sunk in 1816 to supply 7640 barrels of water a day. Samuel Davey Liptrap junior had held onto the business in a renewed partnership with Thomas Smith, but in 1821 he was bought out for almost £40,000, leaving Thomas Smith & Co. in control. The Ducking Pond site and wedge of land between Watson’s Buildings (Winthrop Street) and Buck’s Row (Durward Street) was taken on a 99-year lease in 1829. As was general, basic distilling and rectification (generally the addition of juniper for gin) were separated in the 1830s, Thomas Smith & Co. running the distillery, James Scott Smith & Co. a rectifying house. James Scott Smith and George Smith undertook substantial rebuilding in 1845, but the distillery closed in 1861. Its greater northern part was then given up for the south end of the Great Eastern Railway’s Whitechapel Coal Depot, another plot on the north side of Buck’s Row was sold off in 1874 in connection with the making of the East London Line.2

-

London Metropolitan Arcives (LMA), Land Tax returns; CLC/B/192/F/001MS11936/400/639857: The National Archives, E133/150/63, pp. 1–5: London Gazette, 1 Aug. 1811: Transport for London Group Archives (TfLGA), LT002051/2230: Julian Woodford, The Boss of Bethnal Green: Joseph Merceron, the Godfather of Regency London, 2016, pp. 148–53 ↩

-

Samuel Morewood, An Essay on the Inventions and Customs of Both ancients and moderns in the use of Inebriating Liquors, 1824, p. 303: Oxford University Museum of Natural History Online Collections, WS/G/2/0/045: Outline of the Geology of England and Wales, 1822, p. 44: LMA, Tower Hamlets Commissioners of Sewers ratebooks; M/93/138; SC/PM/ST/01/002: TfLGA, LT2009/450; LT002051/2299; /2309: The Builder, 24 May 1862, p. 380: Post Office Directories: Brian Strong, ‘The development of the London distilling industry before 1820’, London’s Industrial Archaeology, vol. 10, 2004, pp. 43–55: Derek Morris, Whitechapel 1600–1800, 2011, p. 52 ↩

Whitechapel Coal Depot and Great Eastern Square

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 3, 2018

The first direct contact of the northern parts of the parish of Whitechapel with railways came when the Great Eastern Railway Company built a long snaking range of coal drops (or shoots) south from Bethnal Green onto the northern parts of what had been the Whitechapel Distillery until 1861. This opened as Whitechapel Coal Depot in 1866, but from the 1880s was known as Spitalfields Coal Depot. It was a substantial structure, six sidings on a long viaduct, the 52 arched vaults of which were let to merchants and filled with coal. It closed in 1967, but the structure survived until the late 1980s.1

The formation of the coal depot was doubtless behind a proposal from the Great Eastern Railway Company in 1864 that the wide part of Buck’s Row between Thomas Street and the Ragged Schools (on the site of 6 Durward treet) should be renamed Great Eastern Square. This was approved by the Metropolitan Board of Works but appears never to have been adopted.2 Even so, the open space was a gathering place where in the 1890s ‘Jews assemble on Sundays and speechify’.3

Buck’s Row gained great notoriety in 1888 upon the murder here of Mary Ann (Polly) Nichols by ‘Jack the Ripper’. Together with White’s Row it was renamed Durward Street in 1892, with seemingly random reference to Walter Scott’s novel, 'Quentin Durward' (1823).4

-

Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society, Newsletter, Dec 1984: Victoria County History, Middlesex, vol. 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green, 1998, pp. 89–90: Goad map, 1890 ↩

-

Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes, 19 Feb and 8 April 1864, pp. 229,385 ↩

-

London School of Economics Library, Booth/B/351, p. 243 ↩

-

London County Council Minutes, 25 Oct 1892, p. 938 ↩

S. Schneiders & Son's factory

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 3, 2018

Sadok Schneiders, a Jewish immigrant from Amsterdam, was making caps in Whitechapel from the mid 1840s. Moves to Stepney and Bow indicate success that was reinforced by his son Michael who established S. Schneiders & Son’s large hat and cap factory on the north side of Buck’s Row, on the south part of the land that had been the distillery and that now houses the Whitechapel Sports Centre. The eastern section of this was sold as surplus East London Railway property in 1876; there three five-storey and attic blocks were built in 1879–81. John Hudson was probably the architect. The premises were extended westwards with three more blocks in 1892–3 for a continuous eighteen-bay frontage.1 Schneiders employed ‘a rough but respectable set of young women’.2 Two thousand (mainly women) were thrown out of work by a devastating fire in 1901, but reinstatement followed and the factory made clothes and caps for the military during World War One, the workforce successfully striking in 1916 against having to buy trimmings from the firm at elevated prices. After the Second World War Schneiders remained one of East London’s largest wholesale clothing factories, a still largely female workforce making overcoats, suits, jackets, trousers and sportswear, in both branded ready-to-wear and bespoke forms. The premises were purchased by the Greater London Council in 1966, Schneiders moving to Basingstoke while also continuing as tenants for a few more years until clearance in the 1970s.3

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), ACC/0224/13: District Surveyors Returns: Jill Waterson, ‘Cap Makers in Mid Nineteenth Century Whitechapel’, 2010, see http://www.history- pieces.co.uk/Docs/Capmakers_Whitechapel_1851.pdf: The Builder, 22 Nov 1884, p. 713: Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes 15 July 1887, p. 124 ↩

-

London School of Economics, Booth/B/351, p. 243 ↩

-

Los Angeles Herald, 29 June 1901: District Surveyors Returns: LMA, GLC/AR/BR/34/004349: Post Office Directories: D. L. Munby, Industry and Planning in Stepney, 1951, p. 194: Samantha L. Bird, Stepney: Profile of a London Borough from the Outbreak of the First World War to the Festival of Britain 1914–1951, 2011, p. 40: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02b2m63 ↩

Shopping-mall schemes

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 4, 2018

From 1972 to 1988 there were plans for a large shopping mall to the north of Whitechapel Road and Whitechapel Station. These were initiated by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which owned land north of Durward Street and was in the process of acquiring Greater London Council owned property, and planned co-operatively with London Transport, which owned most of what lay to the south of Durward Street. A first scheme incorporated substantial office and residential elements and proposed building above the railway line. The factories north of Durward Street and the housing between Durward Street and Winthrop Street were cleared in the early 1970s, leaving just the coal-drop viaduct, Rosenbergers and Brady House on Durward Street, Brady Street Dwellings, and a garage immediately south of the Jewish Burial Ground in Bethnal Green.

The Shankland Cox Partnership put forward four development options in 1975, soon reduced to three, ranging in extent from just the east side of Whitechapel Station to Brady Street, to all the way to Vallance Road in the west. Redevelopment planning extended well northwards into Spitalfields and Bethnal Green. Abbott Howard, architects, took forward a preferred scheme before 1979 when the Council briefed Sam Chippindale Development Services to prepare a plan for almost fourteen acres ‘loosely based on a Brent Cross/Arndale theme’; Chippindale, a founder of Arndale, had not previously been active in London.1 Through Trip and Wakeham Partnership, architects, this had become a huge project (larger in fact than Brent’s Cross) extending to the northern boundary of the parish, intending 800,000 square feet of retail including six or seven department stores, 300,000 square feet of office space, flats and parking for 1800 cars and a bus station.

There was perceived competition from Surrey Docks, but all seemed set to go ahead in 1983. However, two big retailers pulled out and Chippindale, voicing doubt (the project ‘hadn’t got a cat in hell’s chance of succeeding’2), was sacked in 1985. The scheme’s commercial viability was further questioned, but concerned at being the only London borough both not to have a large retail centre and expecting a population increase in the 1980s, the Council issued a new development brief. Competing proposals included a scheme by Inner City Enterprises submitted with the Tower Hamlets Environment Trust on behalf of the Whitechapel Development Trust. This became known as ‘the community plan’; its architects were CZWG. A more commercial rival (more offices and parking, less residential) from Pengap Securities Ltd working with Chapman Taylor Partners was favoured. Pengap was taken over by the Burton Group in 1987 and the project was passed around, to former Pengap directors as Wingate Property and Investment, then to Chase Property Holdings and on to Trafalgar House with Consortium Commercial. The scheme they submitted and gained permission to build in 1988 would have had a large domical central feature and a nine-storey tower on Brady Street. It would also have meant clearance of 235–245 and 287–317 Whitechapel Road. But negotiations unravelled and by the end of the year the project had died, its abandonment said to be connected to proposals for the Grand Metropolitan owned Albion Brewery site. Meanwhile there had been vast quantities of fly-tipping on the empty land, to a depth of 2–3m.3

What had been the Kearley & Tonge site south of Vallance Gardens was used for car auctions, as a lorry park and as a Sunday market for second-hand goods in the 1980s and 90s. A spin-off from Brick Lane’s then gentrifying market, this was misleadingly referred to as Whitechapel Waste, and more accurately described as the 'kalo' (Bengali for black) market.4

-

Transport for London Group Archives (TfLGA), LT000682/089 ↩

-

East London Advertiser, 1 Nov 1985 ↩

-

TfLGA, LT000682/089: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), cuttings and pamphlets 022: The Spitalfields Trust newsletter, 1990 ↩

-

THLHLA, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Whitechapel Shopping Centre Development Brief, 1986: http://philmaxwell.org/?p=13334: Juber Hussain at https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/616/detail/ ↩

Whitechapel Sports Centre

Contributed by Survey of London on Jan. 4, 2018

Following the failure of shopping-mall schemes, plans for developing the five- acre area north of the east end of Durward Street were advanced in 1991 by the Spitalfields Development Group, headed by Michael Bear with John Miller and Partners as architects, proposing 118 low-rent flats (58) and houses (60) and a public leisure centre with two swimming pools, a leisure pool having been part of the shopping-mall scheme from 1986. This ‘community benefit package’ was put forward as part of a deal for the redevelopment of the Spitalfields Market site.1

A second scheme was submitted in 1995 and after approval in 1996 work went ahead on the building for Tower Hamlets Council of the Whitechapel Sports Centre, with funding from English Partnerships and the Bethnal Green City Challenge. Pollard Thomas & Edwards were the architects, working with Price & Myers, structural engineers, and Hall & Tawse City, contractors. Completed in 1998, the sports centre opened in 1999 as a low- slung irregular block with saw-profile east-light roofing. A single-storey gently curved red-brick screen to the street has cogged bands for decorative texture. Certain facilities are reserved for women only, to take account of the local Bangladeshi-origin population’s preferences.2

-

East London Advertiser, 27 Sept. 1991: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Whitechapel Shopping Centre Development Brief, 1986 ↩

-

RIBA Journal, June 1998, pp. 40–45: Tower Hamlets planning applications online: http://pollardthomasedwards.co.uk/project/whitechapel- community-sports-centre/ ↩

Whitechapel Distillery in 1817, drawn from a survey at London Metropolitan Archives (SC/PM/ST/01/002)

Contributed by Helen Jones