London Metropolitan University's Buildings

Contributed by Survey of London on Aug. 2, 2019

All the buildings between Goulston Street and Old Castle Street south of

Arcadia Court and Herbert House, as well as one building on the east side of

Old Castle Street, are occupied by London Metropolitan University (LMU). That

institution was created in 2002 through the merger of the University of North

London and London Guildhall University. Several of the buildings had since the

early 1970s been occupied by one of the last’s predecessors, the City of

London Polytechnic. These buildings, of the 1900s to the 1960s, were

originally offices, warehousing and packing facilities for the Brooke Bond tea

company. From the 1990s university use spread north to the site of the

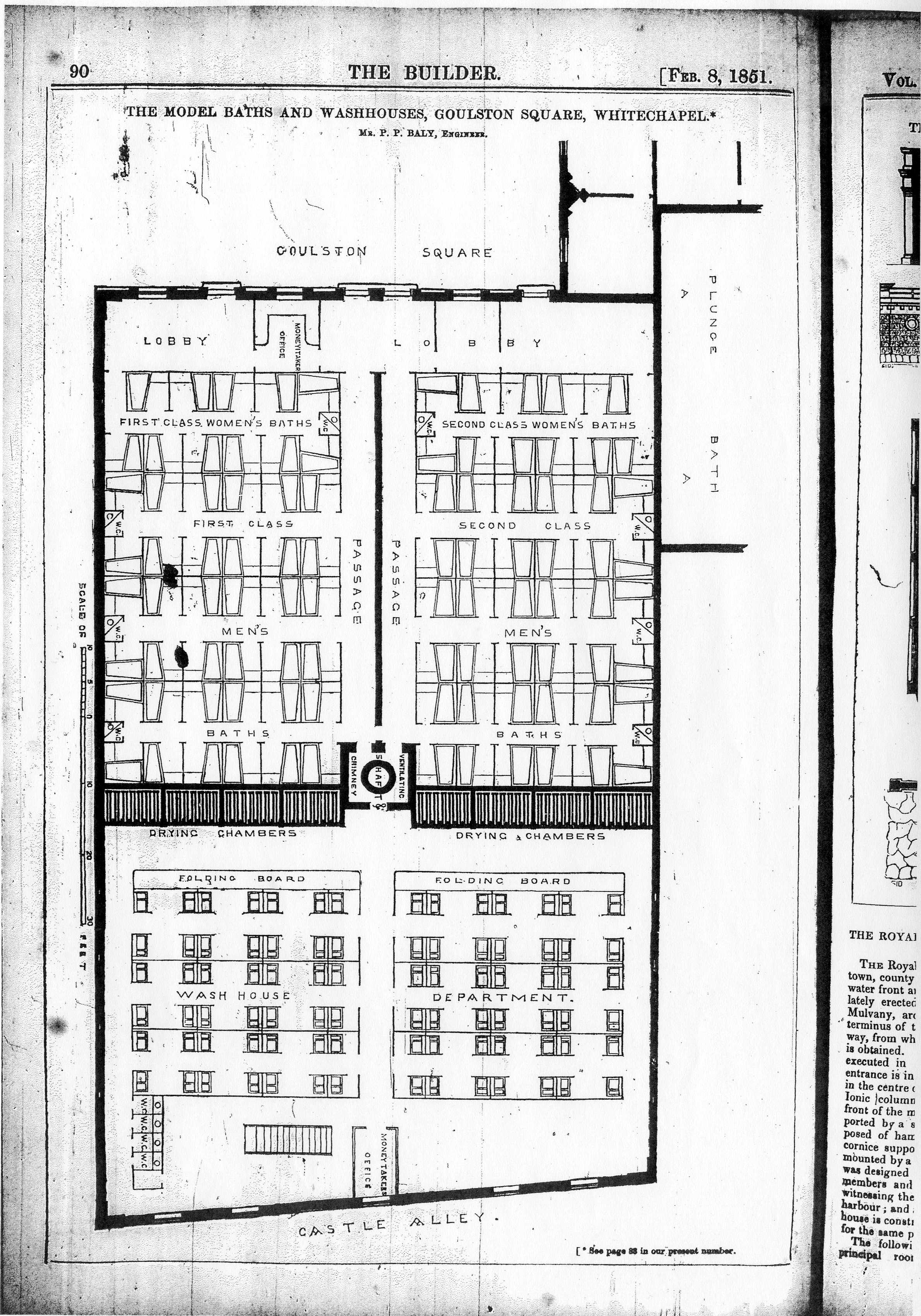

Goulston Square Baths.

Brooke Bond and Calcutta House

The dominant building on the LMU site is Calcutta House, the core of which is

a packing factory built in two stages in 1910 and 1913–14 for Brooke Bond Ltd,

tea dealers and blenders. This firm had been founded in 1869 by Arthur Brooke

(1845–1918), a retailer of tea and coffee in Manchester, who within two year

had five shops in Manchester, Leeds and Liverpool and had moved into

wholesaling, which soon came to dominate the business. In 1873 Brooke Bond

opened London premises at 58 Cheapside and 129 Whitechapel High Street,

expanding greatly in the following decade, and offering a profit-sharing

scheme to its 154 employees by 1882.

The High Street property included stores to the rear that acquired a frontage

when Old Castle Street was widened. Brooke Bond acquired other sites cleared

in the road widening and from 1888 to 1895 built and rebuilt (following a

fire) warehousing at 3–9 Old Castle Street. This may have been to the designs

of the architect William Dunk; the buildings resembled his surviving warehouse

at 31 West Tenter Street.

Further northwards expansion followed from 1909, with the acquisition of the

site south of the public baths that had been David King & Son’s builders’

yard. The architects of the first and northern part of the large steel-framed

packing factory built here in 1910 were Sidney Stott Oldham in conjunction

with Dunk, the builders G. Parker & Sons of Peckham. With five storeys

over a basement, the former factory is red-brick faced to Goulston Street

where the set-back building line of Goulston Square was maintained, the

recessed southern bays leaving space for loading. Stone dressings include a

bold arch-headed door-hood and narrow round-headed high-level staircase

windows with keystones. Elsewhere vast rectangular windows light the former

packing floors, and there is stock brick to the plainer Old Castle Street

elevation. The broader southward extension of 1913–14, designed by Dunk &

Bousfield and similarly constructed, was separated from the original building

by a light well (covered by a steel bomb-proof cover in 1915). The packing

floors extended into the former tenements that had been built with St Paul’s

German church, emptied in 1914. There was thus an incongruously Gothic

appendage to the warehouse’s Goulston Street front.

Brooke Bond expanded yet further across Old Castle Street, taking the frontage

opposite its complex, a shallow site that included the Green Man pub (see

below) extending back only to Tyne Street. This was redeveloped in 1931–2

initially as a warehouse but converted during construction to be a staff

welfare centre. Designed in a tentatively Expressionist manner by Albert Leigh

Abbott (1890–1952), it was erected by local builders Walter Gladding & Co.

Ltd. It is a four-storey and basement steel-framed building faced in brick and

patent stone, with large steel-framed windows by Crittall Ltd. Entrances at

either end lead to staircases and a lift was placed at the north end. An

enclosed footbridge has always connected what was the top-floor directors’

dining room floor to Brooke Bond’s main building opposite. The ground floor

included a workers’ lounge and dance room with a sprung maple floor, the first

floor the workers’ dining room, the second the office-staff dining room and

kitchens. Well specified, with teak joinery throughout, the building was also

technologically advanced – a radio-gramophone piped music to speakers in all

the rooms.

Brooke Bond’s buildings were seriously damaged in the Second World War, the

1890s warehouses at 3–9 Old Castle Street completely destroyed. In 1946 Abbott

oversaw repairs and designed a temporary light-steel structure for 3–7 Old

Castle Street. The former church tenements at the south end of Goulston Street

were replaced with a plain four-storey range. The basement of the ruined

church and a surviving part of its schools were also taken over.

By 1949 J. Stanley Beard was Brooke Bond’s architect. He designed the

warehouse and packing building that went up at 7–9 Old Castle Street in 1951,

extended south to Nos 3–5 in 1955. This was to house paper stores, tea

packers, tea-chest repairs and engineers, and incorporated a large loading

bay. It is in the Utility style typical of much 1950s rebuilding locally,

faced in red brick with steel strip-windows in thin concrete frames. Beard,

who designed Brooke Bond’s blending factory in Bristol in 1959, designed

further three- and four-storey warehouses for the south end of Goulston

Street’s east side in 1961. Built in 1964–5, these were for paper stores and a

sales department above loading bays to the north and a maintenance office and

stores to the south.

In 1968, after a century of expansion tied up with the British Empire,

especially north-east India, Brooke Bond merged with another multi-national

food producer, Liebig, inventors of the Oxo cube. Its Whitechapel buildings

were soon given up.The City of London Polytechnic was formed in 1971 as a

result of policies given impetus by the publication in 1966 of a White Paper,

A Plan for Polytechnics and Other Colleges. The science and technology

departments of Sir John Cass College (whose art department already had a

Whitechapel presence in Central House) amalgamated with the business-focused

City of London College. The former Brooke Bond buildings were taken over in

1972 and in 1974 adapted to reflect the science focus and integrated as

Calcutta House by Fitzroy Robinson and Partners, architects. Basements

included specialist labs (microbiology, neurophysiology, ‘toxic procedures’),

and the 1950s building on Old Castle Street had an ‘animal room’, with fish

tanks, birds and mammals. Upper floors had lecture rooms, offices, a refectory

and lounge. The former welfare centre on Old Castle Street was given a

language lab in the basement and a library on the first floor.

The Women’s Library and later developments

In 1992, the City of London Polytechnic was granted university status as

London Guildhall University. A year later it acquired the derelict former

public baths to the north of its existing premises with permission for change

of use and a view to expansion for library, computing and exhibition space,

conference facilities and office and teaching areas. The University hoped

finally to find suitable accommodation for the Fawcett Library, acquired in

the 1970s from the Fawcett Society, which had its origins in the London

Society for Women’s Suffrage, and housed unsuitably in the basement of

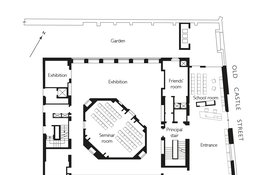

Calcutta House. An outline scheme of 1995, in a feasibility study by Jones

Lang Wootton, proposed redevelopment on the L-shaped footprint of the baths,

with a typical early-1990s feature, a corner octagon, on Goulston Street. The

Fawcett Library would be set back from Old Castle Street behind a ‘suffragette

garden’. Only the east or Model Baths side of the site was developed

initially, following a competition won in 1995 by Wright and Wright

Architects. Construction in 1999–2001 with Kier as main contractors cost £4.4

million, funds coming from private and public donors, the Heritage Lottery

Fund being the most significant.

The client’s brief requested the new library ‘feel permanent’. Wright and

Wright’s design made use of thick concrete walls which contributed to a

restrained architectural aesthetic while improving environmental performance.

As in Baly’s Model Baths, design was technology-led, ornamentation shunned in

favour of efficiency and ventilation. Yet, in a notably if not uniquely

intelligent instance of façadism, the practice elected to retain the Old

Castle Street front wall of 1846, a gesture to a kind of continuity as

thousands of women had come through here. The building behind occupied only

about three quarters of the plot’s width, space to the north given up to be a

paved garden with silver birches behind the stepping down north wall of the

baths. In its dignity and pragmatism, the building was regarded by the

architectural press as a ‘model of politeness’. Indeed, it was the willingness

to engage with the site’s history that Claire Wright believed won the

architects the commission. Behind the punctuated black-painted façade, a

substantial red-brick block steps back, rising to five storeys above a

basement. Internally, accommodation was arranged around a central ground-floor

exhibition space within which there was a pod-like double-height seminar room.

A modest staircase led to a first-floor café lit by the arch-headed windows of

the 1840s façade. Upper floors housed the archive, reading rooms and a double-

height library across the front of the building with a shallow barrel-vaulted

ceiling. Connections between these diverse and interlocking spaces led The

Architectural Review to laud the building for possessing ‘the elegant

complexity of a Chinese puzzle’. It has been argued that the rejection of

conventional spatial hierarchies was a self-consciously feminist act. In 2002

the Women’s Library was awarded the RIBA Journal’s ‘Best UK Building of the

Year’ Award.

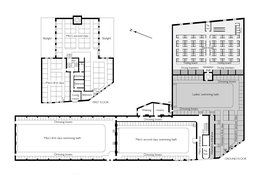

London Guildhall University gained backing from the Higher Education Funding

Council for England for redevelopment of the Goulston Street side of the

former baths site in 1999, but works had not begun in 2002 when it merged with

the University of North London, another former polytechnic, based in Holloway

Road. This was the first merger of two universities, and the new London

Metropolitan University was in its student numbers the largest university in

the UK. The Goulston Building, as it became, went up in 2003–4 as a law and

business school. Also designed by Wright & Wright, it was built by

Willmott Dixon, contractors. The long and undemonstrative range echoes the

red-brick elevations and strip windows of Calcutta House’s post-war buildings.

There is a recessed entrance at the four-storey south end giving access to a

long double-height top-lit corridor that is a common room and exhibition

space. Teaching rooms originally included one configured as a mock courtroom.

The building also incorporates barrow storage for Petticoat Lane market at its

north end. The former warehouse of 1964–5 at the south end of Goulston Street

had its loading bays infilled with glazing in 2004 to the designs of Robert

Hutson architects, to create another double-height reception area, this

building being otherwise devoted to library and study space.

The Women’s Library lasted only until 2012. London Metropolitan University,

hit by funding crises including a ban on international students, could no

longer afford to run it and the collection was sold to the London School of

Economics. In efforts reminiscent of those to save the baths on the same site,

the ‘Save The Women’s Library’ campaign gathered a petition with over 12,000

signatures and the backing of prominent supporters including RIBA President

Angela Brady. One protester reflected that the Library and its award-winning

home belonged together, like ‘a body and its insides’, but to no avail. In

2015 Molyneux Kerr Architects altered the interior by replacing the seminar-

room pod with a lecture theatre. The University’s own archival collections

were brought to the site, along with the Trades Union Congress Library, the

Archive of the Irish in Britain, and the Frederick Parker Collection, over 200

chairs and archives relating to the history of British furniture-making.

Following the sale of Central House in 2015, the Cass School of Art was

relocated to Calcutta House in 2017 on a temporary basis pending the intended

consolidation of London Metropolitan University on a single site at Holloway

Road, the size of the student body being much reduced following the ban on

overseas students. ArchitecturePLB and Willmott Dixon Interiors oversaw the

adjustments. The Architecture Department moved to the Goulston Building, law

departing for Moorgate, and the former staff-welfare building on the east side

of Old Castle Street was refurbished to create workshops and studios.

Other studios and related space in Calcutta House were intended ‘for a design

life of only two years’, but in 2019, as growth returned, it was announced

that LMU had scrapped its ‘one campus, one community’ plan and that the Cass

would remain at Calcutta House.