Central House

early 1980s offices, site of Jewish Working Men's Institute, built 1883, and Great Alie Street Synagogue built 1895, later Half Moon Theatre

Central House, site of 23–37 Alie Street (including 25 Camperdown Street)

Contributed by Survey of London on May 6, 2020

Until the early 1980s, when they were cleared for the site’s present building, 23–29 Alie Street were shophouses, workshops and a former synagogue of various scales and dates. No. 23 was a tall four-storey building that, though it looked earlier with its first-floor relieving arches, was built in 1874–7 by and for Thomas Peters, a carpenter–builder who had moved from No. 33, giving himself a yard and workshops to the rear. The ground floor was opened up for carriage access to the yard in 1907–8. No. 25 was a comparatively diminutive early nineteenth-century two-storey and garret survivor of a pair with No. 27, and No. 29 was another small shophouse that had been rebuilt after the Second World War.1

No. 27 was more interesting. It was built and consecrated in 1895 as the Great Alie Street Synagogue replacing the shophouse pair to No. 25. Dr Hermann Adler, Chief Rabbi, prayed at the laying of the foundation stone that the building would ‘stand forth … in the strength and beauty of usefulness’, and indeed this synagogue did serve the local Jewish community longer than any other in the Goodman’s Fields area. The congregation was formed through a merger of the Windsor Street Chevra and the Kalischer Synagogue, the last having occupied two rooms in Tenter Buildings on St Mark Street for twenty- five years. Great Alie Street, the seventh model synagogue built under the supervision of the Federation of Synagogues, was designed by Lewis Solomon, the Federation’s architect, to accommodate over 250 people; Harry Richardson was the builder and interior decorations were executed by L. D. Weiberg. The pedimented four-storey stock-brick façade was relatively forthright by the Federation’s generally discreet standards. The ground floor provided separate male and female entrances. To the rear the premises broadened on a site that had been occupied by a rag warehouse. A ladies’ gallery spanned three sides of the hall. In 1903 repairs and alterations forced a brief closure and re- consecration. What was later known as the Alie Street Synagogue failed to stabilize after a number of mergers and the declining congregation amalgamated with the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue. It vacated the Alie Street building in 1969.2

The former synagogue was converted to become the Half Moon Theatre, a fringe or alternative venue formed by young actors and artists. Michael Irving and Maurice Colbourne, who already lived in the building, were joined by Guy Sprung, Artistic Director. The theatre opened in January 1972 with Bertholt Brecht’s In the Jungle of the Cities and succeeded as an independent left- wing theatre outside the mainstream. The Half Moon attracted something akin to the excitement engendered by the Goodman’s Fields Theatre in 1741. It has been retrospectively described as having been ‘the most enterprising and consistently challenging and exciting theatre in London’.3 Stained-glass windows, Hebrew scripts and other synagogue fittings were preserved, as were the entrances and pilasters to Alie Street. The Half Moon colonised other buildings to the rear and 25 Alie Street became the booking office in 1980. By then the theatre’s ambitions had outgrown its premises. Plans for a move to Wilton’s Music Hall collapsed in 1977 and the Half Moon moved in 1979 to a former Welsh Chapel at 215 Mile End Road, enabled by grants from the Arts Council and Tower Hamlets Council. The final performance at Alie Street in February 1982 was a double bill of A Yorkshire Tragedy and On the Great Road. After financial difficulties, the Half Moon Theatre was dissolved in 1990.4

From 1883 the Jewish Working Men’s Club and Lads’ Institute was at 31–37 Alie Street. It replaced a small eighteenth-century court that had been reconfigured for trade by the 1870s; there was a similar early court on the site of Nos 27–29. The Jewish Working Men’s Club had been established in Aldgate in 1874, arising out of Sabbath Reading Rooms at Hutchison House, Hutchison Street, on the City side of Middlesex Street. The club was primarily social in intent and aimed to appeal to young men, through educational lectures, as a forum for liberal ideas, and with space for leisure activities. It was a member of the Working Men’s Club and Institute Union, unusually it accepted women as members. Samuel Montagu was its founder and its President until 1908. Membership consisted mostly of skilled labourers and artisans, while management was firmly middle class. By 1881, the club had outgrown Hutchison House. A new building was required if it was to cater for ‘lads’ (teenage boys) as well as men.5

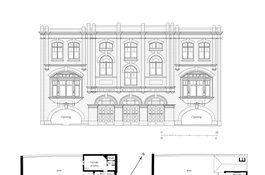

Montagu facilitated the purchase of the Alie Street site and a purpose-built clubhouse was inaugurated in February 1883. Davis and Emanuel, architects, had designed it and John Grover was the builder. At the time of opening, the club claimed 1,300 adult members and 330 boys. The three-storey brick building was mostly set back from Alie Street, and accessed centrally via portico arches below a protruding staircase tower (Ill. – Jewish Working Men’s Club, elevation and plans). The ground floor housed a library, reading room, conversation room and committee room; billiard and bagatelle rooms were in the basement. A large music hall with seating capacity of 640 occupied the whole first floor. Though the building was squeezed between densely packed workshops and houses, open space to the rear allowed the rooms to be lit from both north and south elevations. On the club’s opening, Montagu lauded it as a ‘Palace of Delight’ for working men and women, and the Jewish Chronicle enthused that it was by far the most comfortable of any of its kind in the country.6

What were judged to be inadequate fire escapes soon led to a long-running dispute with the London County Council. Alterations and additions were finally agreed and carried through in 1891 to designs by Lewis Solomon, this time with Samuel John Scott as the builder. Solomon expanded the accommodation towards Alie Street, building out around the central staircase block to create more circulation and service spaces. The extension also allowed for the expansion of some existing clubrooms and the creation of a girls’ room, a room for the use of friendly societies, and storage for gymnasium equipment, enabling the music hall to be additionally used for physical recreation. Solomon also effectively redesigned the Alie Street façade, which was of yellow stock bricks dressed with red bricks and Corsehill stone. Maintaining its symmetry, Solomon punctuated the elevation with a distinctive array of arched windows, varying in scale and form, composed playfully so as to reflect the movement of the staircases and half-landings behind. Two large Queen Anne-style bay windows lit the main first-floor reading room and clubroom.7

Relying on subscriptions to fund activities and not serving alcohol, the club was praised for being self-supporting. It was here in 1896 that Theodor Herzl gave his first public speech on political Zionism. However, membership began to shrink after 1900. Tenancy of the building was transferred in 1913 to Monnickendam Rooms Ltd, an established East End catering and confectionery business that ran private banqueting rooms. The entrance was embellished with representations of flowers, fruit and urns and the interiors were adapted. In 1931, the basement and ground floor were converted to use as tailoring workshops, while the Royalty Ballrooms operated above. In 1936 the building was given over entirely to commercial use. That continued until around 1980 when it was demolished.8

The large eight-storey office building that stands on the site of 23–37 Alie Street and extends back to Camperdown Street was built in the early 1980s, to designs by C. A. Cornish Associates, architects, for the Western Heritable Land Company Limited. The flat brick-faced Alie Street elevation incorporates brick-arch flourishes in a vaguely neo-Georgian form that seems to be an attempt to respond to the eighteenth-century houses it faces. Initially, insurance and financial service companies were the principal occupants, in particular the US-based St Paul International Insurance Company, which led to the block becoming known as St Paul House. The building underwent full refurbishment after 2010, with an enlarged entrance at 25 Camperdown Street. This gives access to the head office of Centrepoint, a charity supporting homeless young people, from which the name Central House perhaps arises. This north-facing elevation is blankly commercial, glass vertical planes framed by dark brick.9

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), District Surveyors' Returns (DSR): Census: Post Office Directories (POD) ↩

-

Jewish Chronicle (JC), 14 Dec 1894; 17 May 1895; 31 May 1895; 18 Sept 1903: DSR: Goad insurance map, 1887: www.jewishgen.org/jcr- uk/London/EE_alie/index.htm: LMA, ACC/2893/133 ↩

-

G. McGrath, Cinemas and Theatres of Tower Hamlets, 2010, p. 31 ↩

-

www.stagesofhalfmoon.org.uk/places/alie- street/: Tower Hamlets planning applications online (THP): London Express, 12 March 1971: The Stage, _5 July 1979, p. 1: G. McGrath, _Cinemas and Theatres, p. 31 ↩

-

POD: Richard Horwood's maps: Ordnance Survey maps: JC, 24 May 1872; 4 Dec 1874; 17 Nov 1894; 1 April 1881; 2 Dec 1881; 20 Nov 1891: D. Gutwein, The Divided Elite: Economics, Politics, and Anglo-Jewry, 1882–1917, 1992, p. 151: E. C. Black, The Social Politics of Anglo-Jewry 1880–1920, 1988 ↩

-

JC, 16 Feb 1883; 23 Feb 1883, p.5 ↩

-

LMA, GLC/AR/BR/19/2411; Collage 116966; DSR: JC, 17 July 1891; 27 Nov 1891 ↩

-

London County Council Minutes, 28 Oct 1913, p. 823: LMA, GLC/AR/BR/19/2411: _Oxford Dictionary of National Biography _sub Moses Gaster ↩

-

THP: www.travelers.co.uk/about-us/history: POD: www.barrgazetas.com/project/camperdown- street.php: beta.charitycommission.gov.uk/charity-details/?regid=292411&subid=0 ↩

Alie Street Synagogue, 1971

Contributed by Survey of London on May 3, 2017

A view of Alie Street Synagogue and adjoining buildings, now demolished, from a colour slide in Tower Local History Library and Archives:

Looking north east down Alie Street with Central House on the left, August 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Nos 4-12 on the south side of Camperdown Street from the east in the early 1970s (photograph by Dan Cruickshank)

Contributed by Dan Cruickshank

Nos 4-12 on the south side of Camperdown Street from the west in the early 1970s (photograph by Dan Cruickshank)

Contributed by Dan Cruickshank

Jewish Working Men's Institute, c.1891, elevation and plans - drawing by Helen Jones

Contributed by Survey of London