Memories of Betty Heller, b. 1909

Contributed by CharlesHeller on June 6, 2017

Betty Heller, nee Rebecca (Rivka) Isenstein, was born in Whitechapel in 1909 and died in Stoke Newington in 2006. The following are brief extracts from the pages of reminiscences that she wrote in her old age.

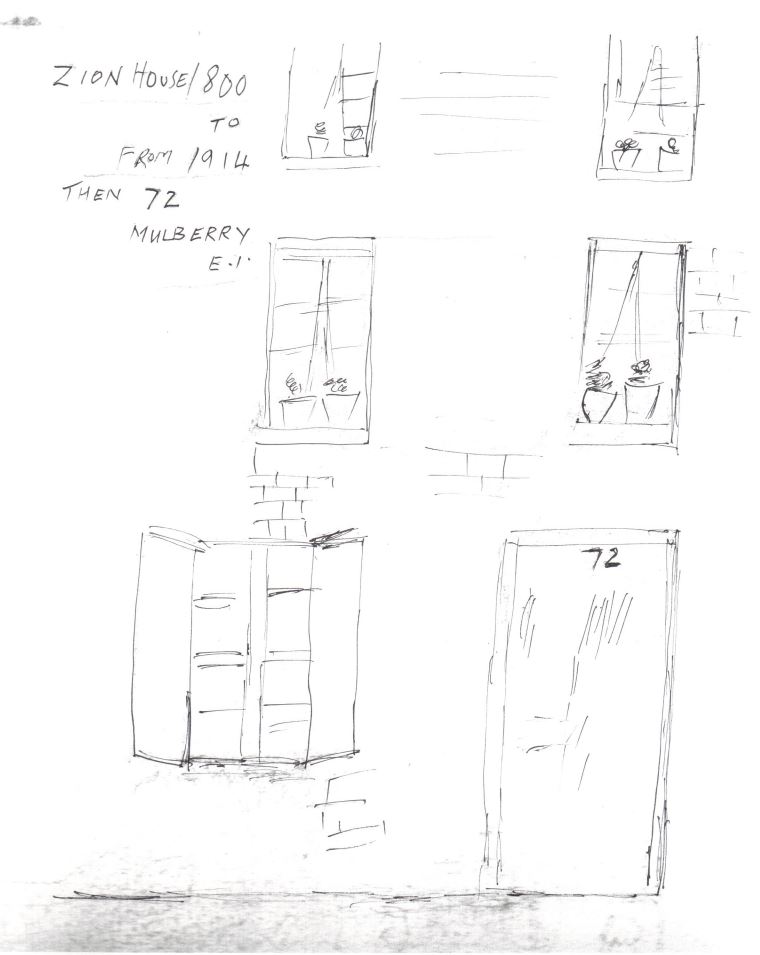

Betty grew up as one of 5 children to Esther and Israel Isenstein, a Polish- Jewish bookbinder living in a block of apartments called Zion House, in Zion Square, Mulberry Street. Latterly her house was known as 72 Mulberry Street. The building and square were obliterated in the Blitz; today’s Mulberry Street is a completely new street. The square occupied the site roughly to the north- east of today’s Mulberry Street. It is shown on the 1894 OS map.

Betty’s earliest memories were of the sound of bells being tested in Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which backed onto Zion Square –“One note repeatedly sounding until it was perfect”, she wrote. Her father’s workshop was on the first floor, and the only light on the crooked stairs was a paraffin lamp on a shelf installed by her father. He would tell his customers in his broken English: “Mind the treppen! [steps]”

The square was used as a playground: it had a swing, and space for the boys to play football, cricket, rounders and roller-skating. The girls put up a rope across the whole square and would line up for skipping games 1. Others would play marbles and gobstones (a game involving flicking and catching small game pieces). In the summer a roundabout would appear and the children would fight for places on the toy horses (the boys would get there first).

There would be a hurdy-gurdy playing hits from Rigoletto, and a barrel-organ playing “Daisy, Daisy” and “Lily of Laguna”, complete with a monkey gazing at the children with sad and sympathetic eyes.

On Good Friday, Father Thomas from the Catholic church on the square would put up a colourful banner which fascinated the children, and one of the neighbours would give him a box to stand on when he gave his sermon (which was unintelligible to the Yiddish-speaking audience).

Mulberry Street itself led from the square to Commercial Road. It had one gas lamp, and Betty would love to watch the lamplighter come round each evening to light it.

Street vendors would pass by every day: “Hokey pokey penny a lump!” from the ice-cream man; “All-British Watercress!”; and at four o’clock the young muffin-man with a huge tray on his head would ring his bell and cry “Muffins! Muffins!”

There would also be doctors visiting children to give them medicine when they had whooping cough, measles or chicken pox. Some would go around on foot; but Dr Lynch would arrive in his horse-drawn carriage and demand 10 shillings for his visit.

The children were sent every day to get milk from the black and white cow at Mrs Woolsey’s dairy, next door to Evans Dairy at the corner of Mulberry Street and Commercial Road; and they would take Esther’s homemade cakes and tshulent (meat stew for Sabbath) to the baker to be put in his oven.

During the First World War Zeppelins loomed over Mulberry Street. Children hid under their desks as bombs were dropped. People were terrified that a bomb would hit Buck and Hickman’s armaments factory on Whitechapel Road, but miraculously the bombs missed. There were rumours that the sweets lying on the streets had been dropped by the Germans and were deliberately poisoned…

Rebecca, called “Becky” by her friends, went on to St Martin’s School of Art and became a dress designer. In order to advance in British society, she felt it was essential to suppress her Jewish background, and insisted on being called “Betty”. In her 90s she would never respond to nurses who called her “Rebecca”, and she was suspected of being demented. When the nurses were persuaded to call her “Betty” (or even “Mrs Heller”) she reverted to her normal alert self.

-

Here is how Betty remembered one of the skipping rhymes 90 years later: "Down in the valley where the violets grow, There is a maiden, she grows like a rose, She grows, she grows, she grows so sweet, Dear little [Annie] come along with me…" A very similar rhyme is recorded in Iona and Peter Opie, The Singing Game (OUP 1988, p.129) ↩