Concert-room beginnings

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 7, 2018

Around 1818 Allrich Eden, an immigrant Hanoverian sugar-worker who by 1808 was

a Cable Street victualler, became the tenant of the Prince of Denmark public

house at 1 Graces Alley and changed its name to the King of Denmark. Following

Eden’s death in 1826, his son-in-law, James Lemon, advertised the

establishment as the Mahogany Bar public house, presumably boasting of what

would then have been an exceptional fitting made of imported Caribbean wood,

long since lost. Matthew Eltham, a lighterman who was building wealth through

property, acquired what formally remained the Prince of Denmark public house

in 1828, probably also taking No. 2 to its west under Marsh’s lease of 1807.

The Sailors' Home having opened at the other end of Graces Alley in 1835, in

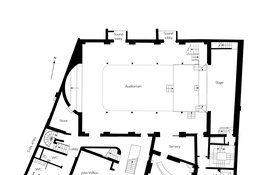

or about 1839 Eltham built a concert room behind the pub, oriented

north–south, about 40ft long with a 20ft-wide stage at the back. Separate

access would have been through No. 2. An opening up of regulations in the

Theatres Act of 1843 prompted Eltham to secure a licence that year to open the

Albion Saloon Theatre, intending enlargement to put on full-length stage

plays. But this entailed restrictions on the sale of refreshments, notably

drink, and in what was an established sailors’ pub, was doomed to fail. Eltham

gave up his licence after two months. He sublet to William Collins who

obtained his own licence for a saloon theatre in January 1845 and began

rebuilding to the rear. The front building collapsed in June, taking with it

adjacent properties at 17 Wellclose Square and 2 Graces Alley; the

construction work was blamed. The luckless Collins fell victim to fraud then

bankruptcy and the lease reverted to Eltham. The Prince of Denmark and 2

Graces Alley had been rebuilt by September 1846, the pub slightly widened at

the expense of No. 2 which continued to be used for separate access to the

back room. The new façade, advertised as ‘of noble elevation’, was embellished

with bracketed cornices and first-floor pediments. Behind the pub’s three-bay

front a single first-floor ‘spacious club room’ was heated from both sides.

No. 3, in Eltham’s hands by 1849, was also rebuilt around this time, its

façade similarly treated. No. 4 remained separate, occupied by Benjamin

Wright, a locksmith and bellhanger.

The Mahogany Bar Mission and rag-warehouse use

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 7, 2018

The freehold of 1–3 Graces Alley and Wilton's Music Hall was sold in 1887 to

John Watson, a Methodist preacher and builder based in Tottenham, who sold on

to the London Wesleyan Methodist Mission (later the East End Mission), founded

in 1885 close by in Cable Street to bring evangelism, temperance and social

work to bear on poverty and squalor under the superintendence of the Rev.

Peter Thompson. Conversion of what was called the Old Mahogany Bar and

Wilton’s Music Hall to be the Beulah Gospel Mission Hall ensued in early 1888,

the works by Watson. They included a new gallery entrance, corridor and

staircase between and behind 3 and 4 Graces Alley. The former pub became a

coffee room, No. 3 a private dining room below bedrooms, the stage a crockery

store. The place was generally known as the Mahogany Bar Mission, and the hall

was used for services. Plans to form an opening in the party wall between 3

and 4 Graces Alley in 1901 were abandoned by Thompson, still then the

Superintendent.

The Mission was open to all in its work to mitigate poverty and deprivation.

By 1930 it hosted an ‘Ethiopian Club’ for African seamen. It continued in the

‘Old Mahogany Bar’ up to 1956 when in the face of post-war depopulation, costs

of maintenance, surrounding dereliction and with the prospect of clearance

looming, it sold up. The Coppermill Rag Sorting Warehouse acquired the

premises for recycling dressmakers’ offcuts into cloths for wiping ships’

engines. The façade stuccowork had been stripped off, probably in 1953 when

war-damage repairs were carried out.

Graces Alley

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 7, 2018

The alley from the north-west corner of Marine Square was first called Boat

Alley in 1683. Felix Calverd, a brewer, tax farmer and Fire Office trustee

associate of Nicholas Barbon (who undertook the development of Wellclose

Square), was then assigned the superior interest of the frontages. Leases were

given to Francis Hooper for the east end of the north side, Charles Armistead,

west end of the north side, and William Blackwell, south side. Building work

was doubtless slow to get underway, but in early 1694 Calverd was taxed for

eight empty houses at Well Close. George Jackson, a City bricklayer, built at

least two 14ft-frontage houses on the alley’s south side in 1694–5 under a

lease from Calverd to Edward Wright, a Clerkenwell glazier.

By 1720, with its frontages fully built up with ten houses on each side, Boat

Alley had come to be known as Graces Alley, a reference to the former abbey of

St Mary Grace that had stood on the site later occupied by the Royal Mint.

Next to Wellclose Square on the north side at 1 Graces Alley was the George

Prince of Denmark’s Head, or Prince of Denmark public house, the name a nod to

the square’s Danish church and occupancy – Prince George of Denmark and

Norway, Queen Anne’s husband, died in 1708. This pub was part of Hooper’s

block of ten houses which passed to Benjamin Collyer, a Surrey merchant. In

1732 John Harper, a citizen needlemaker, was given a new lease of the whole

row on the north side of Graces Alley to run to 1805. Soon thereafter Collyer

was obliged to sell and by the 1770s part of a larger property, which also

included fifteen houses along the south side of Cable Street, was divided in

the ownerships of Edmund Probyn, William Coward and the Duke of Bridgewater.

Leases were co-ordinated to fall in together in 1805.

John Yarrem, a silversmith and hardware dealer or toyman, was at 4 Graces

Alley by 1760. In the years around 1800, Benjamin Abrahams, a slop (clothing)

seller, was at No. 2 and George Holding, a confectioner at No. 3. In December

1807 Probyn, the Earl of Bridgewater and Ann Jemima Wroughton issued new

leases for the unusual term of 46 years; rebuilding was probably associated.

William Marsh, a publican, took 1–2 Graces Alley, the former continuing as the

Prince of Denmark. Holding and Yarrem’s son, also John, continued respectively

at Nos 3 and 4, which appear both, like the alley’s other houses, to have been

two full rooms deep at this juncture.

Shop use was general along both sides of the alley through the nineteenth

century. After many years as an empty site, 7–8 Graces Alley were rebuilt in

1897–8. The American Stores beer house was at No. 10 in the decades either

side of 1900, and the Royal Standard public house was at the west end of the

south side, on the Well (Ensign) Street corner.

Up to the 1960s the stretch of Cable Street immediately north between Well

Street and Fletcher Street had a row of around twenty early- and mid-

nineteenth-century three-storey shophouses, which included the Bricklayers’

Arms at No. 26, and the Admiral Blakeney’s Head at No. 56 on the Fletcher

Street corner. When general clearance of Graces Alley and both sides of this

stretch of Cable Street was programmed in the early 1960s, the houses on the

south side of the alley had already been demolished. Particular complaints

were made about an unlicensed club at 7–8 Graces Alley, owned by George

Gavrilides and frequented by ‘coloured men’. Clearance of all but 1–4 Graces

Alley and what had been Wilton’s Music Hall ensued by 1968.

John Wilton and the music hall: 1850 to 1881

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 7, 2018

John Wilton, a butcher’s son and former solicitor’s clerk from Bath, took over

the pub in 1850 and in 1853 employed Thomas Ennor, a local builder, to put up

a new Mahogany Bar Concert Room on a similar north–south footprint to that

which had been built by Matthew Eltham. Jacob Maggs, a Bath painter-decorator

cum artist, supplied designs. This room was superior in having shallow

balconies on three sides on cast-iron columns and a small bar to the west of a

northerly stage behind a wood and canvas proscenium. Entrance and escape were

initially only through the pub. With improving and respectable aims in a

difficult neighbourhood, Wilton managed a new and increasingly popular form of

musical entertainment, his wife Ellen being an active partner. The premises

were known from 1854 as Wilton’s Music Hall. In 1855 Wilton acquired 2 Graces

Alley and, with S. Charles Aubrey of Dalston as his surveyor, revived its use

for circulation to and from the hall with a new stone-paved entrance hall and

a stone staircase with cast-iron candelabrum newels, its upper landing on iron

rails, a makeshift arrangement that endures.

Wilton was sufficiently successful as to be able to acquire 3–4 Graces Alley

and to rebuild ambitiously in 1858–9 on a scale and with a panache to match

London’s leading music halls, again working with Maggs and Ennor, perhaps also

Aubrey. Ellen Wilton laid a foundation stone dedicated to Apollo on 9 December

1858 and the venue reopened in March 1859 as Wilton’s Magnificent New Music

Hall. The acquisition of No. 4 and rebuilding with a reduction in depth of

this heretofore two-room deep house created space for the building of a

substantially larger hall oriented east–west across the gardens of 1–4 Graces

Alley and 17 Wellclose Square. Aligned with the backs of Cable Street’s

properties, not with Graces Alley, the hall’s position left irregular

circulation spaces and voids between it and the houses along the alley.

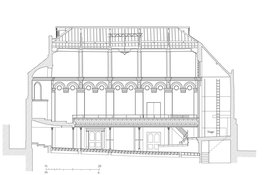

The hall was indeed, and still is, magnificent. With good proportions (about

75ft long by 40ft wide and 40ft high) and excellent acoustics, a priority for

Wilton, the balconied space has a barrel-vaulted ceiling with ornamental ribs.

Five-bay side walls are articulated by capped piers with ten-bay high-level

arcades over circular windows.

A simple proscenium arch provided standing space in the wings of an originally

apsidal stage backed with Gothic-framed mirrors; there were no tableau

curtains or flys for scenery. On the other three sides a carton-pierre bombé-

fronted balcony with swags and acanthus ornament stands on helical-spiral

load-bearing cast-iron columns, an apparently unique feature, at least as a

survival. The floor would have been flat for supper-room seating. A shallower

apse to the west was probably behind a refreshment counter at ground level.

There would also have been a servery in the gap between the pub and the hall

near the stage, a significant indicator of the relationship of auditorium to

public house. Henry Mayhew’s collaborator, Bracebridge Hemyng, explained that

Wilton had ‘erected a gallery that he sets apart for sailors and their women.

The body of the hall is filled usually by tradesmen, keepers of tally-shops,

&c., &c.’

Decorative plasterwork was by White and Parlby, ‘subdued white, relieved by

the gold, grounds being blue and red.’ A spectacular central sunburner

fitting and four other cut-glass gas chandeliers were by J. Defries &

Sons. The sunburner’s was ‘a solid mass of richly cut glass in prismatic

feathers, spangles and spires’.

Facing the alley, No. 4 gained bracketed cornices to harmonise and storey

height as at the pub, taller than Nos 2–3. Probably contemporary was the

unified stucco facing of the whole ground-floor frontage, with a continuous

fascia for advertising and the ornamental surround to the wide foyer entrance

at No. 2.

Madrigals, glees and excerpts from opera featured prominently in the hall’s

performances at first, along with attractions from the West End and beyond,

and from circuses, ballet and fairgrounds. Eminent solo singers of comic songs

included Sam Collins, later Jolly Nash and George Leybourne (Champagne

Charlie). There were also trapeze artists and can-can dancers. The stage was

squared off under a simple lean-to loft sometime before 1871 when there was

still supper-room seating.

Wilton continued to run the music hall as a model of propriety and order until

1868 when he moved to the West End, retaining freehold ownership of other

Graces Alley property. His first successor was George Robinson, who moved on

to the Royal Oak in 1872, perhaps having run a less genteel house than

Wilton’s. Harry Hodgkinson was the proprietor in August 1877 when fire broke

out during refurbishment works, gutting the interior of the hall and

destroying the roof. Little was left within the walls save parts of the

balcony on ‘tottering’ columns. Insurance money permitted hasty like-for-like

reconstruction and reopening in September 1878, just in time to avoid having

to comply with new fire regulations that led to the closure of many small

music halls. The works were executed under the supervision of J. Buckley

Wilson, of Wilson, Willcox and Wilson, architects; the builder, otherwise

unidentified, was called Jones. Reinstatement with reused columns was as

before, save for the insertion of a more theatre-like raked floor. Tastes had

been changing and audiences declining. Perhaps more significantly, the MBW’s

safety demands imposed further work or hefty fines. Despite the expense of the

rebuild, Wilton’s Music Hall closed in 1881.

Rescue from demolition and revival schemes: 1960s to 1980s

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 7, 2018

The London County Council’s Graces Alley Compulsory Purchase Order of 1963

included the former Wilton's Music Hall in its schedule for clearance. A year

later demolition was still planned, with an intention to form a record as an

awareness of the building’s special character and significance to theatre

history was spreading. Colin Sorensen, later a curator at the Museum of

London, had been a visitor and worker at the Old Mahogany Bar in the Mission’s

later years and had photographed the building. Geoffrey Fletcher also drew

attention to the place in 1964. But it was John Earl, then an architect at the

Ministry of Public Buildings and Works with a special interest in theatre

history, who played the key role. Earl, who had first encountered Wilton’s in

1951, led the way with Sir John Betjeman in forming the British Music Hall

Society and in preparing a case for the listing of what was now being called

‘Wilton’s’. A public enquiry in September 1964 responded to the new Society’s

representations and the LCC undertook to consider retaining the music hall.

Listing followed in November 1965.

Earl had moved to work under W. A. Eden and Ashley Barker in the new Greater

London Council’s Historic Buildings Division. There he took Wilton’s under his

wing for the next twenty years. In October 1965 Eden urged giving a lease of

Wilton’s to the Negro Theatre Workshop, following an application from its

Artistic Co-ordinator, Christian Simpson, a BBC producer. The possibility

foundered, presumably for want of funding. The CPO was confirmed and the GLC

took vacant possession of the building in November 1966.

The reinstatement of music-hall use was under consideration by August 1967

when the GLC formally decided not to demolish the building. Surrounding

clearances left it, in Earl’s words, ‘a completely isolated, inexplicable

object – a stranded whale’. An early project in 1968 included a

surrounding multi-storey car park above shops and a petrol station, but a road

scheme stymied major action. In that year Universal Pictures carried out

balcony-front repairs and, advised by Sorensen, redecorated the interior in

brown and stone colours that were thought original for the filming of Karel

Reisz’s Isadora in which Vanessa Redgrave dances on the stage. In 1970 the

building gained much wider attention through BBC2’s Boxing Day programme

“Wilton’s” – the Handsomest Hall in Town, directed by Michael Mills,

catalysed by Spike Milligan, and with, among others, Peter Sellers, Warren

Mitchell, Ronnie Barker and Keith Michell as Champagne Charlie. This provided

the occasion for the launch of a fund-raising trust and was the first time the

potential of reviving Wilton’s was realised. Other occasional use for filming

followed.

Considered conversion schemes began to be prepared in 1972 including for the

newly formed Wilton’s Music Hall Trust, led by Peter Honri, an actor with

music-hall roots, who aimed with Earl’s support to establish a National Centre

of Variety Entertainment. He also gained backing from Betjeman, Lord Olivier,

Sir Bernard Miles, Marius Goring, Bernard Delfont and John Osborne. The GLC

formally invited proposals in November 1973, with an expressed preference for

a use associated with music-hall tradition, intending to grant a 99-year

lease.

Eight schemes were submitted. The Wilton’s Music Hall Trust’s, by J. R.

Notman, architect, was seen as worthy and architecturally acceptable, but it

offered no return. In May 1974 the (Labour-controlled) GLC decided to give

preference to an Island Records project, the most commercial option offering

the best return. Fronted by John Pringle with Peter Ustinov as ‘entertainment

adviser’ and backed by Trelawny Investments Ltd, it undertook to bring

Wilton’s back into public use. Don Ashton Design Consultants Ltd prepared

plans for ‘Wilton’s Original Music Hall’ that included an extension, a pub,

restaurant and a fish and chip shop ‘catering to the local public’. Otherwise,

also rans included a scheme from Truman Ltd with Tommy Steele (to be an ‘actor

manager’), and another from the Half Moon Theatre Company, which had been

formed nearby on Alie Street in 1972 and was building a reputation for staging

Brecht and other largely left-wing productions (see p.xx). This had support

from Tower Hamlets Council and the Arts Council.

Island Records pulled out in June 1975 as costs escalated. Led by Pam

Brighton, the Half Moon Theatre Company jumped into the void and worked with

Earl and others at the GLC to prepare a bid for moving to Wilton’s. The Half

Moon was given a six-month option on a lease in February 1976 if it could

raise funds for the first phase of a restoration programme that envisaged a

community arts complex, intending theatre use during the week and variety,

music-hall and concert use at weekends. Grant bids were prepared and the

support of the Historic Buildings Council was secured. A rival bid from the

Wilton’s Music Hall Trust (led by Honri, Goring and Betjeman) was not

favoured. The Half Moon scheme gained improbable support from Peter Drew,

managing director of St Katharine’s-by-the-Tower Ltd, a subsidiary of Taylor

Woodrow, which was redeveloping the nearby St Katharine’s Docks. It was

approved by the GLC’s outgoing Labour administration in March 1977 in the

knowledge that the opposition, led by Bernard Brook-Partridge, the

Conservative arts spokesman, intended to reverse the decision if elected.

They were and it was. Drew then withdrew Taylor Woodrow’s support for the Half

Moon project and the GLC determined that it was no longer financially viable.

Political motives were initially denied while a preference for a fuller

revival of music-hall use was expressed. The new administration approached

Drew seeking a scheme for Wilton’s that did not depend on public money. The

Taylor Woodrow group linked up with Goring and the Wilton’s Music Hall Trust

and in August the GLC decided to give these parties a lease, open to the

possibilities that they might either physically move Wilton’s to St

Katharine’s Dock or ‘recreate’ it there where there were already Dickens and

Beefeater themed tourist attractions. Supported by Tower Hamlets Council, the

Half Moon fought back in a bitter row, in part by staging a production titled

Grand Larceny – the Curse of the Commercial Vampires, and with a ‘Save

Wilton’s for the East End’ campaign. In November 1977 the GLC approved a

scheme for a National Theatre of Music Hall to be taken forward by a new

company involving the GLC, the Wilton’s Music Hall Trust and Taylor

Woodrow.

Honri, as Artistic Director, Drew, Brook-Partridge and associates launched

this company as the London Music Hall Protection Society Ltd (or ‘Friends of

Wiltons’) in early 1978, with plans for ‘Wilton’s Grand Music Hall’ being

prepared by Peter Newson of the Kirby Adair Newson Partnership. Newson was

Drew’s architect at St Katharine’s Docks and St Katharine’s-by-the-Tower Ltd

managed the project. The proposals intended use of the hall as John Wilton’s

Supper Room, with private boxes in the balcony, also envisaging the rebuilding

of 17 Wellclose Square. Goring, Betjeman and other members of the Wilton’s

Music Hall Trust took exception to this scheme and pressed on with an

alternative project close to that they had submitted in 1972–3. This faded as

the more powerfully based group forged ahead with fund-raising, which included

a gala dinner in August 1979 with Liza Minnelli as guest of honour.

In December 1979 the GLC gave the London Music Hall Protection Society a lease

with a building agreement for what was now being called the National Centre of

Variety Entertainment. This was still being run from St Katharine Docks,

though Newson had left work there and continued for Wilton’s as Peter Newson

Associates; even so, transactions with the Kirby Adair Newson Partnership

continued. Estimates for the whole project had risen to £1.2m by the time a

first phase of works was carried out in 1981–2 by Warriner (Builders) Ltd of

Romford. This involved stabilisation, weather-proofing and dry-rot eradication

in the auditorium and relied heavily on GLC and central government grants. A

variety show celebrated completion, and in 1983 Wilton’s was used for the

recording of the video for Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Relax’. Further works

completed in 1985 through Newson, with the Michael Barclay Partnership,

engineers, and Warriners, tackled the houses at 1–4 Graces Alley. This

entailed the rebuilding of the upper parts of the front walls, reroofing, new

windows and reinstatement of the façade’s stucco architraves. By now the GLC

had granted £121,000, the Historic Buildings Council £39,000. With the

structure sound and weather-tight, the project stalled for want of further

funds.

The abolition of the GLC in 1986 was a major setback for Wilton’s. The London

Music Hall Protection Society had reconstituted itself as the London Music

Hall Trust in 1982 and, abolition pending, sought the freehold from the GLC,

still intending to spend about £500,000 on fitting out and completion. After

abolition, the London Residuary Body, mopping up the GLC’s affairs,

transferred the freehold to the Trust and disposed of adjoining lands to

developers, killing off any prospect of enabling development that might have

benefitted Wilton’s. New neighbours, Shapla Primary School and George

Leybourne House, further limited options. Under the leadership of Brian

Daubney, the Trust carried out further stop-start works in 1986–94, though not

as much as was intended. Newson departed in 1990 and was succeeded by Bucknall

Austin Project Management Services. Builders were Warriners, W. & R.

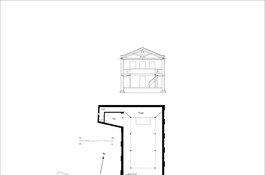

Buxton Ltd and James Longleys. No. 17 Wellclose Square was demolished and

rebuilt to provide dressing rooms and other backstage spaces, including a lift

and an external rear escape staircase. Plaster was systematically stripped to

prevent dry rot and interiors were otherwise cleared. In 1990 the hall was

given a red décor for the filming of The Krays.

Restoration: 1997 to 2015

Contributed by Survey of London on Dec. 7, 2018

The use of Wilton’s for (unheated) live performances was revived in 1997, when

a production of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land by Deborah Warner with Fiona

Shaw brought acclaim, in part on account of the hall’s attractive dereliction.

With an eye on the recently established Heritage Lottery Fund as a possible

source of largesse, the London Music Hall Trust restructured in 1998, setting

up the Wellclose Square Building Preservation Trust to lease the property to

the Broomhill Trust. Broomhill, a self-styled ‘radical opera company’ led by

Mark Dornford-May, took on the management of Wilton’s, opening with a

production of Kurt Weill’s Silbersee, translated by Rory Bremner as

Silverlake, a story of murderous violence arising from lottery madness.

Other productions followed with the idea that sustained use of the venue would

stimulate funding for refurbishment works. Despite support from English

Heritage and the Theatres Trust, plans by Pierce Hill Project Services Ltd for

extensive alterations were stillborn and in 2003 Wilton’s was an unsuccessful

finalist in BBC’s _Restoration _programme competition for funding. Bankruptcy

loomed.

In 2004 Broomhill moved to South Africa and David Pennock became Chairman and

Frances Mayhew Artistic and Managing Director of what was now reformed once

again as the Wilton’s Music Hall Trust. Prince Charles became the Trust’s

patron but in 2007 a Heritage Lottery Fund application was turned down as

premature, approval extending no further than a condition survey. Hugh Grant

and Helen Mirren backed a fund-raising campaign and the National Trust

considered acquiring Wilton’s.

Regrouping under Mayhew’s leadership and with awareness of Wilton’s spreading

all the time, in 2011 the twin trusts, lessee and freeholder, sought £2.4m

from the Heritage Lottery Fund for a ‘Capital Project’, a programme of works

estimated at £3.5m presented in a bid titled ‘Wilton’s Music Hall “Saved,

Revealed and Alive”’. This proposed works in three phases to complete

restoration of the hall then the houses, to be overseen by Tim Ronalds

Architects, with Philip Cooper of Cambridge Architectural Research as

structural engineer. Crisis loomed when the application was rejected, but a

donation of £700k from SITA Trust and further contributions from other trusts,

foundations and individuals to £1.1m permitted work to start on the first

phase, the conservative repair of the hall/auditorium. This was carried out in

2012–13 with Fullers Builders as the main contractor. A revised application

was thrown back to the Heritage Lottery Fund which now, in 2013, gave Wilton’s

£1.9m of the £2.5m still needed. Numerous other funders made up the shortfall.

Refurbishment of the houses was carried out in 2014–15, with William Anelay as

contractors. Final total costs were just under £4m. Wilton’s Music Hall was

declared fully open in September 2015 with a staging of The Sting.

Faced with a largely unaltered Victorian music hall that had undergone

piecemeal repairs, restorations and redecorations, and substantially altered,

stripped-out houses, Tim Ronalds Architects adopted a conservative approach,

stabilising not restoring, avoiding even redecoration in favour of leaving

surfaces alone. Pragmatic exceptions were made in replacing the back stairs

behind 4 Graces Alley and in mounting a new lantern over the main entrance.

Elsewhere, the as-found ethos extended even to leaving _in situ_a bird’s nest

uncovered during the works. Even so, the spaces in and behind the houses were

brought back to full use. An irregular sequence of connected first-floor bars

includes a ‘cabaret cocktail bar’. The Mahogany Bar was kept going, keeping

its match-boarded ceiling and fragments of Victorian ornament, now with a bar

that copies the hall’s balcony fronts, recycled from a production. The

Heritage Lottery Fund support came on the back of strong commitments to

community participation and learning, including an exhibition space on the

ground floor in 3 Graces Alley.