Darbishire Place (Block M)

2012-15, Peabody flats replacing Block K destroyed in 1940 | Part of Peabody Estate Whitechapel

Darbishire Place

Contributed by Christine.Wagg

Block K had been destroyed in the Blitz and the site was cleared and left vacant for many years. Eventually it was replaced by a new block designed by Niall McLaughlin, and named Darbishire Place in honour of the architect who designed the original estate. The block was a finalist in the Stirling Prize 2015.

Whitechapel Peabody Estate

Contributed by Survey of London on May 1, 2019

The housing to either side of Rosemary Lane in the early nineteenth century was bad even by the low standards of that time. In 1838 Thomas Southwood Smith highlighted the area’s disease-infested insalubrities as exemplifying poor conditions in Whitechapel more generally. Blue Anchor Yard, he said, ‘abounds with narrow courts, in which the accumulation of filth is excessive, and it is scarcely possible for any air to penetrate.’1 In the mid 1840s, John Liddle, Medical Officer of Health to the Whitechapel Union, oversaw paving and drainage improvements in an area that he characterised as having many 200-year old houses. After a serious outbreak of cholera, Thomas Lovick, Assistant Surveyor to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, visited in 1848 to cleanse Hare Brain (elsewhere Hairbrain) Court. He reported that his assistants found it the most offensive place they had encountered. Its thirteen ‘wretched and dilapidated’ houses had thirty-two rooms inhabited by 157 people, the court outside had ‘fish, soil, and offal and refuse of various kinds … strewn about the surface’, and there were overflowing cesspools, with no water supply and pig-keeping.2

Henry Mayhew followed on with reports that the cheap lodging houses in the courts off Rosemary Lane were occupied by poor Irish, many of them street sellers, and ‘dredgers, ballast-heavers, coal-whippers, watermen, lumpen, and others whose trade is connected with the river, as well as the slop-workers and sweaters’. He explained that this was ‘a large district interlaced with narrow lanes, courts, and alleys ramifying into each other in the most intricate and disorderly manner... The houses are of the poorest description, and seem as if they tumbled into their places at random. Foul channels, huge dust-heaps, and a variety of other unsightly objects, occupy every open space, and dabbling among these are crowds of ragged dirty children who grab and wallow, as if in their native element. None reside in these places but the poorest and most wretched of the population, and, as might almost be expected, this, the cheapest and filthiest locality of London, is the head-quarters of the bone-grubbers and other street-finders.’3

There was some rebuilding in the early 1850s, around thirty new houses going up, mainly on Hare Brain Court and in Blue Anchor Yard, but these too were evidently of a poor standard and little else was done. Cholera revisited a district that retained its reputation as one of London’s worst. Once Royal Mint Street had been widened on its north side, there was local dismay in early 1875 when accommodation for railway companies was preferred over the building of artisans’ dwellings as a use for the cleared land.4

Within weeks a major new opportunity opened upon the passage of the Artizans and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875, sponsored by the Home Secretary, Richard Assheton Cross. This legislative milestone made it possible for the first time for the Metropolitan Board of Works to over-ride local reluctance to tackle London’s slums through its own compulsory purchases of areas designated as unhealthy. The idea was that acquisition and clearance by the metropolitan authority would facilitate development by model-dwellings companies. In practice there were significant difficulties and delays as regards land value, compensation and rehousing. John Liddle, now the Medical Officer of Health for Whitechapel District Board of Works, jumped in immediately in July 1875 to make representations as to the urgency of applying the new Act to the area south of Royal Mint Street, citing disease, poor health and housing ‘unfit for human habitation’. He defined a six-acre redevelopment area with a population of about 3,750 averaging more than eight persons per house. Approvals following a local inquiry led to the Whitechapel and Limehouse Improvement Act of 1876, which made this part of Whitechapel the first area anywhere so to be addressed. The legislation stipulated no reduction in overall housing capacity, so the project as first agreed aimed to build tenements to house 3,870. The target was not quite met; after fifteen years of convolutions, thirty-six blocks had been built to house 3,600. The MBW had spent £187,558, almost all of it on buying property and recouped only £35,795 from the sale of land.

Plans adumbrated before the end of 1875 from within the MBW (so prepared under George Vulliamy) proposed widened streets and twenty-one blocks across the whole district, generally laid out as parallel, mostly east–west ranges. One constraint on planning was the Great Eastern Railway viaduct, which bisected the clearance area, others were Peek’s new premises on the west side of Glasshouse Street and the Weigh House School on Providence Place just west of the parish boundary. Robert Vigers, who was surveyor to the Peabody Trustees, was consulted in 1876. He put forward an alternative scheme for blocks laid out more north–south. A year later at the request of the Whitechapel District Board of Works, already deploring delays, it was decided to start at the east end of the area, phasing the project to avoid too much displacement. Terms for letting sites for development were settled in 1878, but complications with purchases, arbitration and rehousing made progress slow.5

The financing of the project, with the MBW generally having to pay market prices and, while keen to minimise losses, obliged to sell for the purpose of working-class housing, played out to make the site unattractive to investors. In January 1879 no buyers could be found when building leases of the easterly ground were advertised envisaging seven blocks. After private negotiations, the Trustees of the Peabody Donation Fund offered £10,000 (only half the MBW’s reserve price) in May 1879 for the freehold of the area around the north end of Glasshouse Street as part of a package that embraced five other sites across London. An auction generated just one bid for the Whitechapel property and none for the others; the Peabody offer was accepted in July. The MBW was thus compelled to sell below its asking price, so accepting a considerable loss and effectively and controversially subsidising tenement construction.6

The Peabody Trust had been building tenement blocks to house London’s ‘respectable’ poor since soon after its foundation in 1862 by George Peabody, an American merchant banker. The Trust’s architect, Henry Astley Darbishire, had introduced courtyard layouts or squares in Islington in 1865 and maintained a consistent and distinctive house style. Darbishire stuck to his preferences, revising the scheme for the Glasshouse Street area to project eleven five-storey blocks (in ten buildings) to house 1,372 in 286 flats with 628 rooms. He ignored the parallel block ideas and introduced a western courtyard or square, albeit compromised by a block at its centre, necessary to meet the required densities. These plans were personally approved by R. A. Cross in early 1880 and this was the first of the MBW’s slum-clearance projects to be taken forward. John Mowlem & Co. had widened the north end of Glasshouse Street in 1879; their granite-sett road surface survives. Blue Anchor Yard was also reshaped. The housing blocks went up in 1880, some not completed until early 1881 when ownership of the land was transferred. William Cubitt & Co., Peabody’s usual contractor, carried out the building work, which cost £57,704.7

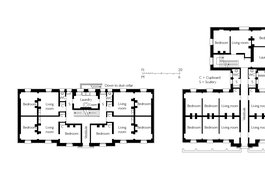

Whitechapel’s Peabody Estate maintained heights of five storeys where other slum-clearance projects of the early 1880s were obliged to rise to six (basement dwellings were not permitted). Despite the density, irregularity in the layout and the detachment of the blocks maintained an openness that made this accidentally one of the more attractive Peabody estates. Outwardly the blocks were standard Peabody structures, if more than usually austere with pale yellow gault-brick elevations broken up only by dentilled bands and cornices. There are terracotta-dressed porches in entrance elevations, those to the west of Glasshouse Street (Blocks D to K) having the central three bays breaking forward, a matter of making space for staircases more than an aesthetic gesture. The internal planning of the blocks followed that used in Peabody estates since 1871 at Blackfriars Road, one- and two-bedroom flats compactly grouped so as to be free of corridors, with a laundry on each floor as had been introduced at Pimlico in 1876. Blocks B and C were different with four-bedroom flats in the main range and single two-bedroom flats and laundries per floor in rear annexes. Block A was another variant that the nature of the site forced on Darbishire.8

Even before they were complete, the Whitechapel Board of Guardians was criticising the Peabody blocks as unsuitable ‘for the class of tenants requiring rooms’ and ‘unhealthy because they are so arranged that no sunlight and little air are admitted’. The District Board of Works also found fault with internal ventilation.9

In July 1881, six weeks after it had opened as the first fruit of the MBW’s slum-clearance efforts, the Whitechapel Peabody Estate was visited by a Parliamentary Select Committee on Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings. The committee found it to be almost fully occupied, by 1,260 people in 286 families, but only eleven people previously housed on the site had moved into the new buildings. Rents, which started at 3_s_for a one-room flat, had risen greatly and it was in any case Peabody policy to aim for ‘respectable’ tenants. The committee had already been told by Liddle that the buildings were inhabited ‘by a superior class to those who have gone away’, mostly Irish, gone he knew not where, the new people being from ‘the artisan class, the respectable class of working men’.10

This kind of tenancy was maintained into the twentieth century. In 1910 Block L was added between Blocks A and B on the east side of Glasshouse Street, on the site of Glasshouse Buildings, an early nineteenth-century court north of Shorter’s Rents that had escaped clearance in the 1870s. W. E. Wallis was Peabody’s architect and William Cubitt & Co. were again the builders. This block of twenty-one flats represents changes in Peabody’s standard forms that had been manifested elsewhere, notably a sixth storey to the centre for a laundry, and white-brick bands in yellow stock-brick elevations.11

Coal stores flanking Block F and bicycle and pram sheds around the estate’s perimeters went up in 1909, 1911 and 1920. A plan in 1931 to replace 53–54 Royal Mint Street with a three-storey block comprising a bathhouse under two three-bedroom flats was not carried through. A communal bathhouse was still intended in 1949, but again not built.12

Block K on the west side of Glasshouse Street was destroyed in the Blitz, on 8 September 1940, killing seventy-eight people, most of whom were in the block’s air-raid shelter. A plaque of 1995 on Block L commemorates this disaster.13

Overall modernisation was carried out in 1967–77 to make all the Peabody flats self-contained, that is no longer ‘associated’ with shared WCs and sculleries. Ward & Paterson Ltd, builders, carried out this work to plans by F. E. F. Atkinson, Peabody’s surveyor. Block D, damaged in 1940 but repaired, was now demolished to reduce density and open up the courtyard. The building’s footprint was retained for a sunken ball-game area within brick walls in 1977 by H. N. K. Gosewinkel Ltd, contractor. Contemplation of a comprehensive redevelopment in the 1970s came to nothing. In 1999 Farrar Huxley Associates relandscaped the playground and gave it play equipment within iron railings.14

The northeast corner gap between Blocks E and F was infilled in 2001–2 with the building of the Threshold Centre at 80 John Fisher Street, Peabody employing Greenhill Jenner Architects and Roper Construction Ltd, contractor. Under a monopitch roof and with bright-red facing, this gave the estate community facilities with an upper-storey children’s play-space/nursery over offices, a meeting room and a computer workshop.15

The site of K Block remained empty save for car parking until 2012–14 when Peabody erected a residential block on the site that it named Darbishire Place. This was built by Sandwood Design and Build, to designs by Niall McLaughlin Architects (McLaughlin working with Tilo Guenther, one of his associates). It provided thirteen ‘affordable’ family flats in five storeys, maintaining the estate’s height, massing and open layout, but extending southwards to make the project financially feasible. It complements without copying the existing brick elevations (the specified colour changed during the design stage when the other blocks were cleaned) and deep white window reveals, here in precast concrete. There is an elegant curved staircase, and balconies overlook the central playground. Darbishire Place was praised for its contextual subtlety and shortlisted for the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Stirling Prize in 2015. The once cramped array of Victorian tenements was now hailed as having ‘a generously dimensioned square’.16

-

Fourth Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners, 1838, p. 145 ↩

-

‘Report of the Select Committee on Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings’, Parliamentary Papers, 1881 (358), pp .8–9: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), MCS/476/043 ↩

-

Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, vol. 2, 1861, pp. 45–6, 140 ↩

-

LMA, District Surveyors Returns (DSR): The Builder, 1 Sept. 1866, p. 655; 3 April 1875, pp. 295–6; 10 June 1876, p. 570 ↩

-

Metropolitan Board of Works Minutes (MBW Mins), 30 July 1875, pp. 178–9; 3 March, 28 April and 16 June 1876, pp. 334–5, 592, 847–8; 9 Nov. 1877, p. 546; 1 March 1878, p. 340 and passim: LMA, MBW/1838/17; SC/PM/ST/01/002: The Builder, 24 Nov. 1877, p. 1181: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), I/MIS/6/1/1: ed. C. J. Stewart, The Housing Question in London, 1900, pp. 112–18: Anthony S. Wohl, The Eternal Slum: Housing and Social Policy in Victorian London, 1977, pp. 92–140 ↩

-

MBW Mins, 4 July 1879, pp. 25–8 and passim: LMA, MBW/1838/17: The Builder, 28 Feb 1880, p. 267: ‘Report of the Select Committee on Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings’, Parliamentary Papers, 1881 (358), pp. 204–5: John Nelson Tarn, ‘The Peabody Donation Fund: the role of a housing society in the nineteenth century’, Victorian Studies, Sept. 1966, pp. 7–38: Wohl, p. 162 ↩

-

MBW Mins, 14 Feb. 1879, p. 232; 26 Nov. 1880, pp. 726–9: LMA, DSR; LCC/VA/DD/167: The Builder, 1 March 1879, p.241; 19 Feb. 1881, p.230: Peabody Archives, WHC.03; WHC.07 ↩

-

Tarn, loc. cit., p. 32: Irina Davidovici, ‘Renewable Principles in Henry Astley Darbishire’s Peabody Estates, 1864 to 1885’, in (eds) Peter Guillery and David Kroll, Mobilising Housing Histories: Learning from London’s Past, 2017, pp. 57–73 ↩

-

The Builder, 26 June 1880, p. 810; 4 Dec. 1880, p. 683 ↩

-

‘Report of the Select Committee on Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings’, Parliamentary Papers, 1881 (358), pp. 10,103: Stewart, op. cit., p. 117: Tarn, _loc. cit._ ↩

-

Peabody Archives, WHC.17: DSR: London County Council Minutes, 14 Dec 1909, p. 1348: THLHLA, Building Control (BC) file 22151: The National Archives, IR58/84824/4148 –4216 ↩

-

DSR: THLHLA, L/THL/D/2/30/129; BC file 22151 ↩

-

THLHLA, P08106: Peabody Times, winter 1996, p.4 ↩

-

THLHLA, BC file 22151: LMA, ACC/3445/PT/08/033 ↩

-

THLHLA, BC file 25375: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

-

Architects Journal, 4 July 2011; 8 Oct. 2015: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

Peabody Estate

Contributed by Christine.Wagg

The estate was built by the Peabody trustees on a site acquired from the Metropolitan Board of Works in one of London's first slum clearance schemes. The blocks were designed by Peabody's architect, Henry Astley Darbishire, and the estate was opened in 1881. On 8 September 1940, the second night of the London Blitz, one block took a direct hit, and nearly 80 people were killed. In 1995 a war memorial listing their names was placed on the external wall of Block L.

Metropolitan Board of Works slum-clearance area and first scheme for redevelopment, 1875

Contributed by Helen Jones

Metropolitan Board of Works, slum-clearance redevelopment, scheme of 1876 and as completed by 1894

Contributed by Helen Jones

Whitechapel Peabody Estate, typical ground-floor plans as built

Contributed by Helen Jones

Whitechapel Peabody Estate, view of central square from southwest in 2019

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Whitechapel Peabody Estate, central square from the northwest in 2019

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Whitechapel Peabody Estate, view through central play area in 2019

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Darbishire Place and Block J in 2019

Contributed by Derek Kendall