Former Royal Oak public house

1873, public house, now shop, restaurant and flats | Part of 118-120 Whitechapel Road

Early history of the site of 100-146 Whitechapel Road

Contributed by Survey of London on April 19, 2018

Long frontages of waste ground on the south side of Whitechapel Road were the subjects of 500-year manorial leases from Henry, Lord Wentworth, in 1585. A 528ft stretch on the site of 100–146 Whitechapel Road, extending back 132ft at its east end so as to include what was to become the site of Vine Court, went to James Platt, a London gentleman; Thomas Wilson, a brewer, already had tenure of the westernmost 66ft. ‘Sundrie’ houses and other buildings were built on Platt’s land by 1658 when Meggs’ Almshouses went up at its west end. This whole Whitechapel Road frontage had been largely built up by 1682.1

Platt’s lands passed via Robert Greaves of Greenwich, to Thomas Bateman (d.1659), a Whitechapel wheelwright. Now in the shade of Whitechapel Mount to the east, they were inherited by Bateman’s son-in-law Edward Conyers, and were sold in 1705 to Edward Elderton, a butcher who had tenure of grazing land to the south that had been owned by Richard Warren in the 1580s as pasture called Cooke’s Close. This was held with Red Lion Farm and together the property was acquired by the London Hospital in 1755 and 1772. By 1730 Thomas Turner, a Whitechapel house carpenter, had possession of this (Platt’s) estate, where there had been a plague pit in 1665 and where Vine Court had been formed, its main east–west part initially known as Walnut Tree Street. Turner died in 1733 leaving his estate to his son Henry Turner, a tobacco pipe-maker in Wapping, who died in 1737 dividing the property between his three sons. The eldest, John Turner, another carpenter, consolidated ownership of the property in 1750 after litigation. Westwards, Tongues Alley had been reshaped as two small yards and Hampshire Court extended south from the west side of Meggs’ Almshouses. Land to the south of Vine Court remained open till the 1790s and the Turner estate was repartitioned in 1817 following lengthy Chancery proceedings.2

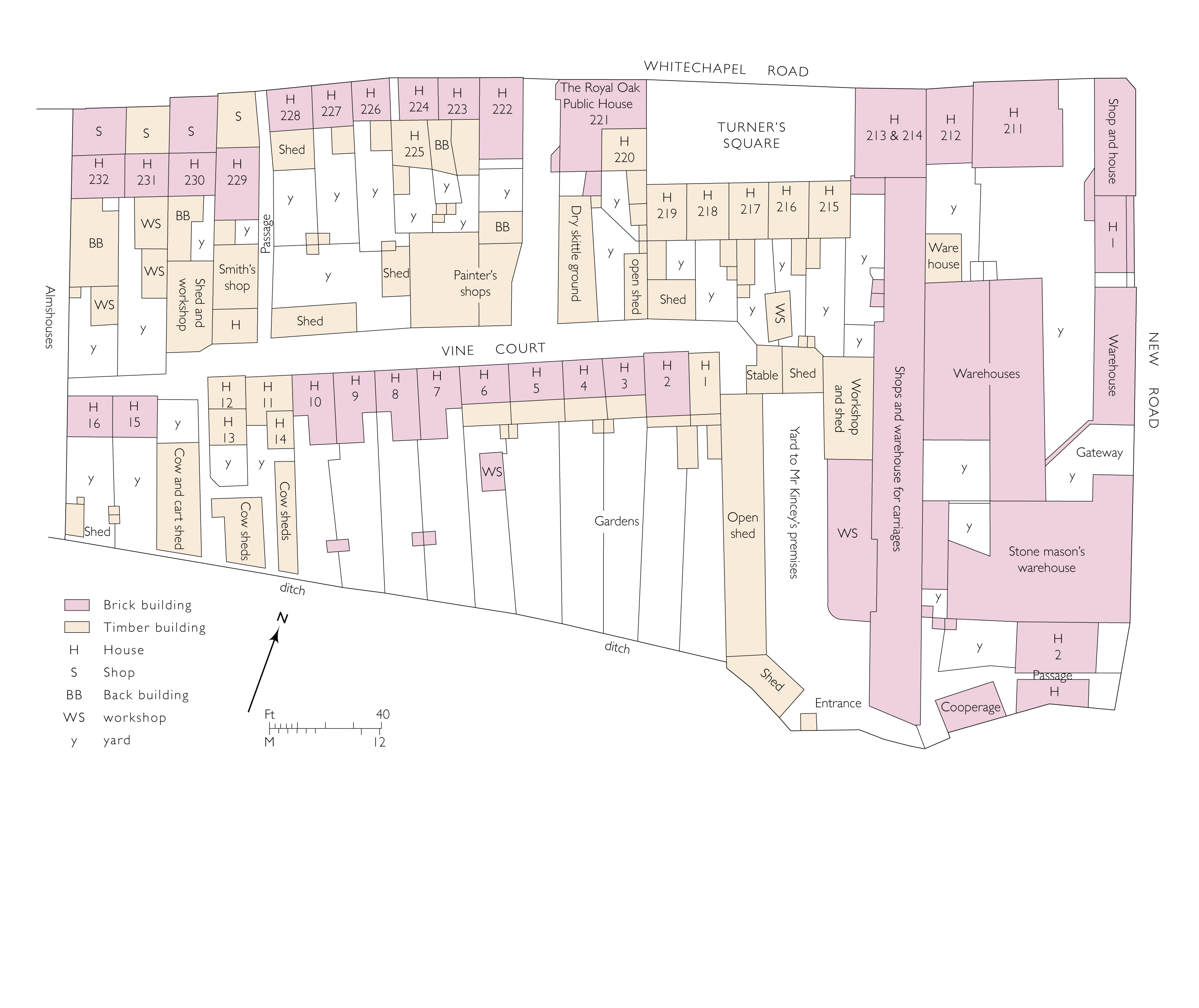

The Turner estate in

1817 (redrawn from The National Archives, C13/2777/49)

The Turner estate in

1817 (redrawn from The National Archives, C13/2777/49)

East of the almshouses the property that Thomas Turner had acquired by 1730 began with a setback row of four houses (at Nos 102–108), with shops added in front by the early years of the nineteenth century (Ill. – Turner estate in 1817, redrawn). Beyond, a 3ft-wide passage called Cock and Horns Court connected to the west end of Walnut Tree Street (later Vine Court). On its other side there were six more brick houses and one of timber, set back and called the ‘whitehouse’. All but two of all these were one room deep. One of the largerhouses, on the west side of the main Vine Court entrance, was further extended to the rear in the 1820s for William Mace, a floorcloth manufacturer. There was then an attached schoolroom over the court entrance.

By 1730 Thomas Turner had, and had perhaps built, a row of five timber houses (on the site of Nos 122–130) set well back from the road. Framed by more forward lying brick buildings the resultant small open space came to be called Turner’s Square. In its early eighteenth-century origins as Walnut Tree Street, Vine Court’s houses included a group called Dupaz’s Buildings, named for Solomon de Paz, a Sephardic Jewish merchant. The court as a whole comprehended about twenty small houses by 1770. On the east side of its entrance a large house (at Nos 118–120) was probably the public house known as the Morocco Slaves in 1730. It later became the Royal Oak. A large brick house on the site of No. 132 that enclosed the east side of Turner’s Square also had early eighteenth-century origins.3 John Kincey (sometimes Kinsey or Kensey), a coachmaker–wheelwright, took a 61-year lease in 1778 and built extensive workshop and warehouse ranges to the rear for coachbuilding. An even larger house on the site of No. 138 was built around 1770 (following a 61-year lease of 1763 to Thomas Pearce and John Lamb) on what had been open ground for William Menish, an innovative chemist who was here until around 1810. In 1776 Menish was accused, but acquitted, of creating at the New Road corner, ‘a nusance, in erecting an elaboratory and making spirits of hartshorn’.4 Menish was followed by John Burnell, a horn manufacturer, who also succeeded Menish at a mill and workshops on the north side of Whitechapel Road further west. There was a large yard to the rear that came to be used by stone masons. Kincey was at the New Road corner (formed in 1754-6) by 1780, with additional proprietorship of a number of small houses in the vicinity. In the decades either side of 1800 many of the occupants along these parts of Whitechapel Road were upholsterers, cabinet-makers, carpenters, harness makers and the like, including an umbrella maker.5

-

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives (THLHLA), P/SLC/1/17/4: London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), M93/176, 202 and 241: Faithorne and Newcourt's map, 1658: William Morgan, London Etc Actually Survey’d, 1682 ↩

-

THLHLA, P/SLC/1/17/4: Gascoyne's map, 1703: The National Archives (TNA), C13/2777/49; C107/175; PROB11/662/22; PROB/683/271: Rocque's map, 1746: Horwood's maps, 1799 and 1813 ↩

-

TNA, C13/2777/49; C107/175; PROB11/799/423: LMA, Land Tax returns (LT); Tower Hamlets Commissioners of Sewers ratebooks (THCS) ↩

-

Lloyd’s Evening Post, 8 July 1776: General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, 30 March 1779 ↩

-

TNA, C13/2777/49: LMA, MS119136/516/1065824; LT; THCS: Post Office Directories ↩

Former Royal Oak public house (with Wilcox’s New Music Hall and the Vine Court Synagogue)

Contributed by Survey of London on April 23, 2018

A public house on the east side of Vine Court’s entrance may have been the Morocco Slaves in the early eighteenth century. It became the Royal Oak, possibly in the 1750s when an establishment of that name might have been obliged to abandon a more easterly location near Whitechapel Mount for the formation of New Road. The Royal Oak was run by the Cragg family in the first half of the nineteenth century, James Cragg, William Cragg and then from the 1830s Richard Riley Cragg, who sought a music licence in 1849.1

Zebedee Wilcox, a ginger-beer maker with a shop on the site of 124 Whitechapel Road, took the licence in 1868 and converted an upstairs room to use as a music hall. This was a success so he took what had been a skittle ground and a yard to the rear beside Vine Court and in 1869–71 designed and built under his own supervision what he called Wilcox’s New Music Hall, a room about 31ft wide by 55ft deep with space for up to 700 people. There was a platform stage at the far or south end with balconies on the other three sides under an enriched plaster ceiling and a hipped roof. This originally bore a large lantern ventilator, removed in 1943. Opened in December 1871, this claimed to be ‘the most comfortable and the finest sounding hall in London’.2 The ‘lofty, handsome building’ had a grand chandelier and decorations by Francis Johnson, a local (Charlotte Street) paperhanger. Buvelot Rattigan officiated, and the Manager was Pat Corri. The place was a success, but Wilcox, perhaps in poor health (he died in December 1873), soon sold up. In July 1872 the music hall closed, ostensibly to permit the building of a ‘handsome frontage’ and completion of the decoration of the hall’s interior.3 If not already at that point, by November the proprietor was George Robinson, who since 1868 had been running Wilton’s Music Hall, latterly in competition with Wilcox. Robinson pulled down the old pub and had it ostentatiously rebuilt in 1873. An intended conversion of the music hall to tavern use was abandoned.

The Royal Oak is no longer in use as a pub, but it stands as a fine example of blowsy Victorian pub architecture, and was listed in 1973. Was Robinson, like Wilcox, his own architect? The wide five-bay three-storey front is of red brick, but so lavishly embellished with stucco architraves and pilasters that this is easily overlooked. There are lacy upper-storey iron balconettes on elaborate corbels, and a half-round attic window beneath a pediment is flanked by half-figure caryatids. The west bay stands over a full-width carriage entrance to Vine Court with brick jack-arching. Two slender ornamental cast- iron colonnettes survive in ground-floor interiors.

Though Robinson's motive in closing Wilcox’s might have been to protect Wilton’s, he left Grace's Alley in April 1873 to base himself at the Royal Oak. But he sold up in 1874 with a defensive advertisement, his ‘colossal building’ having been received with scepticism. Numerous short-lived proprietors followed. Music-hall use appears not to have returned. Up to 1887 the hall was used by the Netherlands Choral Society, a club for Jews of Dutch origin. What were called ‘music rooms’ were deemed unfit to be licensed for that purpose in 1888. Nevertheless, Samuel David Isaacs, proprietor of the pub, carried out alterations in 1890 to adapt what was still called a music hall for Yiddish theatre. Led by Eliyohu Zalman Yarikhovski, who had translated Verdi’s 'La Traviata' into Yiddish, the Oriental Working Men’s Club staged shows here until January 1892 when, unlicenced, it was shut down and Yarikhovski, his brother Benjamin, and others were prosecuted.4

There followed another conversion of the music hall, this time for synagogue use. The Kovno Chevra, founded in 1874 by Lithuanian immigrants, were looking for new premises since the room above stables in Middlesex Street that they were using had been condemned. They found new accommodation here in what became Vine Court Synagogue through an agreement of June 1892 with the brewers Hoare & Co. that excluded use of the cellars. Its committee of management, and the lessees when the synagogue opened in September 1892, were: Benjamin Ritter, a picture-frame maker of 17 Balls Pond Road, Dalston; Wolf Goldstein, a chandler of 12 Chicksand Street; Mark Sallant, a cigarette maker of 70 Brunswick Buildings, Goulston Street; Morris Harris, a tailor of 9 Spelman Street; and Lewis Lewis, a general dealer of 37 Fashion Street. Lewis Solomon, the Federation of Synagogue’s architect, had overseen minor alterations to the already suitably galleried room by June 1894, the works paid for through a mortgage to the Federation and carried out by John Gilbey, a Whitechapel Road builder. Solomon also saw to repairs after a ceiling collapse in 1909 that obliged re-consecration, and further works were carried out in 1924 by Lewis Cohen of Mile End Road. An entrance at the north end of the west elevation gave direct access to the gallery, which had an iron mehitzah over panelled fronts. The Ark on the south wall, flanked by British Royal family prayer boards and under a pair of round-headed windows, was decorated with crowned Luhot (Tablets of the Law) with framing griffins. By Whitechapel’s standards this was a large synagogue and its congregation grew through amalgamations, for example with the apparently Zionist-leaning Jerusalem Hevrah; Whitechapel Road Synagogue merged in 1932, bringing around 200 members to a congregation that regularly comprised around 400 people, further enlarged by transfers from Greenfield Road Synagogue in 1946. Another reopening took place in 1947, after repair and improvements following bomb damage. Thriving into the 1960s, but no longer ‘thronged week by week’, Vine Court Synagogue closed in 1965.5

The Royal Oak became Roosters around 1980, then closed in the 1990s. There are now flats above a restaurant (the Alhambra) and a shop (Salma Designer Abaya House) which also occupies the lower part of the former music-hall–synagogue as 17 Vine Court. Light-industrial (rag-trade) use had been introduced there by the 1970s. Around 2005 the hall was all but wholly rebuilt as a taller three-storey and attic block for twelve flats; one earlier round-headed window survives at the north end of the Vine Court elevation.6

-

London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), Land Tax returns; Tower Hamlets Ccommissioners of Sewers ratebooks; MR/LV/06/049; MR/LV/07/049; MR/L/MD/0315 ↩

-

East London Observer, 27 Jan 1872, p. 4: The Era, 11 April 1869, p. 7; 7 Jan. 1872, p. 13 ↩

-

London and Provincial Entr’acte, 6 July 1872, p. 3: The Era, 16 June 1872, p. 7: Post Office Directories (POD) ↩

-

LMA, MR/L/MD/1781; ACC/2893/192; ACC/2893/333/001; District Surveyors Returns (DSR): Metropolitan Board of Works Minutess, 29 Nov 1872, p. 634 and 31 Jan 1873, p. 148: The Era, 7 June 1874, p. 2; 16 Jan 1892, p.8; 26 March 1892, p.16: The Builder, 29 March 1890, p. 239: POD: https://www.wiltons.org.uk/heritage/history: Jewish Chronicle, 9 Sept. 1892, p. 6: David Mazower, ‘Whitechapel’s Yiddish Opera House: The Rise and Fall of the Feinman Yiddish People’s Theatre’, in (eds) Colin Holmes and Anne J. Kershen, An East End Legacy: Essays in Memory of William J. Fishman, 2017, pp.159–60 ↩

-

Jewish Chronicle, 9 Sept. 1892, p. 6; 11 June 1965, p. 6: LMA, DSR; ACC/2893/190–4; ACC/2893/333/001–4: Gina Glasman, East End Synagogues, 1987, p. 18: Sharman Kadish, The Synagogues of Britain and Ireland, 2011, p. 135: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

-

POD: Tower Hamlets planning applications online ↩

102-128 Whitechapel Road in March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

118-120 Whitechapel Road in March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

116-124 Whitechapel Road in March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Former Royal Oak public house, facade detail, March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Former Royal Oak public house, facade detail, March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Former Royal Oak public house, facade detail, March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall

Former Royal Oak public house, facade detail, March 2017

Contributed by Derek Kendall